“Anger, frustration… hope?” shrugs Joseph Appiah. “When you’re in prison, making music can sometimes be the only way to release the uncomfortable feelings you’ve learned to lock away.”

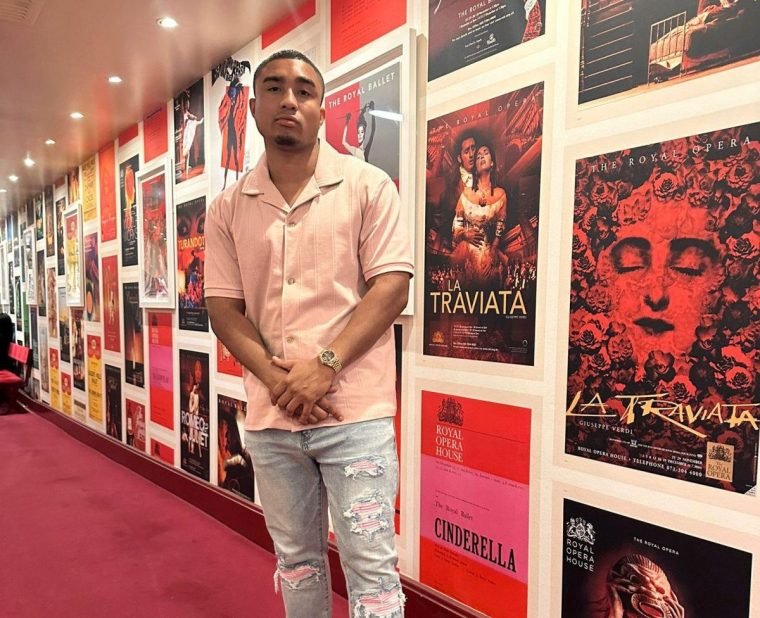

An open-faced, articulate man of 30, Appiah – who now raps, acts and models under the name Cleeshay – was released from prison in December 2022 after serving a 12-year stretch for the controversial crime of murder by “joint enterprise”.

This November he’ll join a group of ex-prisoners performing at “PROGRESS: A night of words, music and culture” at BeauBeau’s independent café in London. The event is organised by Switchback: a charity dedicated to “helping young men build stable, independent futures”.

Leaning forward, hands on knees, at Switchback’s London HQ, Appiah tells me he wrote to Switchback from his cell seeking a mentor to help him navigate life beyond the prison system. The crime that landed him in jail took place back in May 2010, when he was just 15 years old. He was convicted at 16, so has done most of his growing up on the inside.

“I didn’t have the kind of background you’d expect from a guy who’s spent so much time in prison,” he says. “I have supportive, hardworking parents. I passed the 11-plus exam and went to grammar school in Kent. We went on holiday two or three times a year…” Appiah rocks his chair back against the wall and throws up his palms. He tells me his Ghanaian dad worked as a housing officer for Lewisham Council for 20 years. His Japanese mother is a journalist and editor covering the fashion and drinks market. “She’s a proper Japanese mum,” he grins. “So she made sure my little brother and I did at least an hour of homework after school. Then we went to Japanese school on Saturday, so I’ve also got an AS level in Japanese…”

Appiah – who now gives talks about his life to secondary school pupils – is admirably open about how his life took a wrong turn. “In south London there is a lot of trouble,” he explains. “I didn’t have big brothers or cousins. As a teenage boy I started to feel I needed to surround myself with older guys who seemed cool. I didn’t really have any other reason to go down into that life – I wasn’t in it for the money. My parents gave me money…” He shakes his head. He had only known these older boys for six months when what he now refers to as the “mad incident” occurred.

His sentences get shorter as he describes the afternoon on which he joined a group of boys preparing to square up to a rival group after one of his friends had been humiliated in a playground scrap. He admits he expected a fight, but he had no idea this would escalate towards a fatality. “It was broad daylight. School uniform. Took a strange turn.” Appiah was actually 200 yards away from where the stabbing took place. He didn’t even see the murder and there was CCTV to prove it.

Pressure group Joint Enterprise Not Guilty by Association (JENGbA) argue the law is being wrongly used, and told MPs earlier this years that the 1000-plus suspects convicted under the law between 2010-2020 are victims of “a miscarriage of justice on the same scale as the Post Office Horizon scandal”. Figures show joint enterprise is disproportionately used against black suspects.

“I genuinely thought there was no way I would go to prison for something somebody else did,” sighs Appiah, who’s still campaigning to have his conviction overturned. “I thought it would just take a bit of time for them to work out who did what and then I would be OK – I mean, I got bailed and getting bailed for murder is unheard of. It seemed a good sign I was going home. So I didn’t see it coming.”

He was still working on his AS levels. “I was doing Drama, Business, Media and Politics. When I was sentenced I remember sitting in the dock and thinking, ‘I didn’t see my life going this way.’”

Appiah had been incarcerated for two years when he began writing music to process his experience. “In prison, we’re not allowed phones to listen to music on,” he explains. “We have to have CD players, and there was a CD going around of instrumentals for raps. I borrowed it one night and it started something off. I was there with my pencil and paper. Lyrics were coming fast to my head and I was writing them all down in my cell.”

Once he felt he had written some solid songs, Appiah began performing at prison church services. “We could justify me rapping in church, getting up there with a mic because a lot of my music was about faith. I would be asking God what was going on: ‘Why me?’” He says Sunday services were routinely attended by around 50 prisoners and 10 staff, including chaplains. “The feedback was good and that really boosted my confidence.”

On his YouTube channel, as Cleeshay, you can hear him rapping over smooth R&B samples. His face always covered until recently, he spits only “non-fiction/ never lied in the booth”. On “Last Lap” (released in December 2023), he’s frank about prison life: “boiling eggs in my kettle… I hid my phones in the ceiling” and how he felt “finally comin’ out the dungeon/going through depression”.

After Appiah was transferred to HMP Liverpool, he was able to make use of the prison’s recording studio. “I would put down my own songs and I enrolled in a radio production class where we worked on podcasts.” He was able to broadcast his own music on the prison radio station and got another boost when fellow inmates began approaching him to say they’d been moved by his work. “That was my first taste of having an effect on people from a distance.”

Muks, his fellow Switchback mentee, is also 30, and like Appiah he can’t really make sense of falling in with the crowd who led him into dealing drugs. He first went inside at the age of 22 and has served five sentences for drug dealing since then.

“Thing is,” he says, tugging on his beard and looking down at his knees, “My parents both worked long hours. They weren’t at home. So I’d come home from school and be out on the street, and I started to gel with other people. Even though you don’t start your evening looking for trouble, thinking, ‘Lets go and be dickheads’, it can just happen if you’re in an environment where everybody else is doing it.” After he left school, Muks admits he “didn’t really understand the concept of getting a job. I did some low-skilled stuff. Construction. But I took advice from the wrong people.”

Muks had always been interested in music. Through his teens he’d sporadically recorded bits and pieces with friends. In prison he found himself drawing comfort from the prison radio station and started writing his own bars. He’s never performed live – the PROGRESS showcase will be his first gig – but he nervously recites some lines to me now, with his gaze fixed on the floor: “Sittin’ in the can/ Thinkin’ ‘bout my plans/ Thinkin’ will I touch the world?/ Make a hundred grand?/ When will I next kiss a girl or hold my daughter’s hand?”

Towards the end of his last sentence, Muks was visited in prison by a Switchback mentor called Abby. “I didn’t know what to think of her at first, I’ll be honest,” he grins. “But turns out she is proper cool. She helped me out a lot. Asked questions, treats me with respect, holds me accountable.”

Appiah says it’s hard for prisoners to walk away from crime if nobody is rooting for them. “In my case, I always had the love and support of my parents and my brother. I was embarrassed that I’d ended up in prison and I was focused on getting out and making them proud. But most of the guys you meet in prison don’t have that. They ended up inside because they were poor and committed crime to make money. When they get out they’re still poor so they go right back to it. I’ve seen so many get out and bounce right back into prison.”

He doesn’t think the current system offers much rehabilitation. On his song “Lifer’s Perspective”, he notes: “prison ain’t a friendly place, you can get robbed/ I see a man stab a man for an Xbox/ See a man cut his wrists cos his girl’s leavin’.” Today he says: “It can give you time to reflect. But I’ve seen that often leads to worsening mental health conditions. Depression. Drug addiction. In 12 years I reckon I’ve only seen three people actually change.”

This is where he believes mentors – like those provided by Switchback – can help with practical advice, support and emotional engagement. The charity helped Muks get work experience in the film industry. Appiah started out with a work placement in a cafe after his release – a position that went so well he ended up with a permanent job until he moved to live with his partner. Now, among other things, he offers school talks.

“Most mentors go into prisons to build relationships with guys before they’re released,” he explains. “I am not allowed to do that because of my conviction. Instead I get community referrals – they’re put in touch with me by a probation officer or a drugs counsellor.” He says it doesn’t always work out. “I’ve had two drop out: they just want to party. But I’ve got two guys who are locked in, working, and I’m helping them because they know I can relate.”

Appiah says music helped him make sense of “feeling happy, feeling free” after his release. “I became so used to writing deep, low vibration music in prison that I struggled to write more upbeat music at first. I would say it took me about a year to be able to write about my current life, current affairs.”

Like Muks – who’s keen to stay in the film industry but curious about his musical options – Appiah is looking forward to showing the world what he can do at the PROGRESS event. He hopes to forge ahead with a career as a multi-hyphenate artist.

“Live performance really makes the music come to life. I really enjoy using my body, my hands, giving it my all.” After the years of shame and frustration, Appiah and Muks “are just really grateful for the opportunity to make a contribution, make the crowd feel good.”

PROGRESS: A night of words, music and culture will take place on Friday at BeauBeaus Café, London