The character: Tati, one of four members of Los Espookys, a team of horror enthusiasts who stage supernatural events for hire in a fictional, unnamed Latin American country. She works many other jobs, too, including manually moving the second hand of a clock, selling herbal supplements, and writing her own versions of classic literature.

The actor: Ana Fabrega, 31, a co-creator of the HBO series Los Espookys with Julio Torres and Fred Armisen. Included in Vulture’s “Comedians You Should and Will Know in 2018,” Fabrega specializes in a particular kind of deadpan absurdity; she previously wrote for The Chris Gethard Show and has appeared on High Maintenance and At Home With Amy Sedaris.

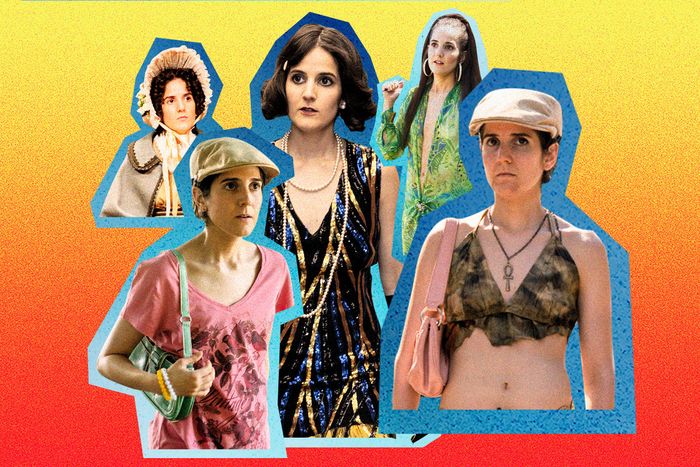

Essential traits: Generally positive attitude, difficulty understanding basic tasks, can see through time and space. Enthusiastic about Los Espookys’ work, even if she often misses the point. Sister to the more practical Úrsula, who tends to view Tati’s antics with concern; ex-wife of gay cookie heir Juan Carlos. When not in costume for an assignment or special occasion, wearing a newsboy cap and carrying a small purse tightly under her right arm.

“A big dummy.”

As Torres, Armisen, and Fabrega developed the series, they came up with a loose idea for each of the personalities in the Los Espookys quartet. “Fred described one of them as a big dummy,” Torres remembers, “and Ana was like, ‘I want to play that.’” As Torres puts it, Fabrega is an “incredibly smart person” who is deeply amused by the ways people can be stupid. “She’s redefining the idiot. It’s almost Chaplin-like,” he says. To Fabrega, Tati provided her an opportunity to combine obliviousness with confidence: Tati earnestly believes what she says, like that an animated prince is in love with her, and the root of her impulses, usually, is to be understood and admired and valued — even if what she ends up doing often sabotages the group. “I wanted her to be dumb, honestly, but stay grounded,” Fabrega says. “The emotional stakes are real for her.”

As they wrote the pilot, the trio came up with the idea that Tati would always be working one-off gigs. “I had been trying to make a series about people who work odd jobs,” Fabrega notes, “so I thought I could just roll that into Tati.” As they continued to write the series, she and Torres put together a list of possible tasks Tati could perform; in the pilot, she’s working as a fan by spinning a fan’s blades manually. “One of us either saw or made up seeing a cleaning person at an airport bathroom hitting the ‘positive’ green button to rate your experience in the bathroom,” Torres says. “In our world, Tati would be hired by the cleaning person to keep hitting the green button.”

Other traits developed from Fabrega’s background. She grew up speaking Spanish at home but primarily speaks English as an adult unless she’s visiting family in Panama; as a joke explanation for her accent, the writing team established that Tati studied English in Minnesota for two weeks and came back with an accent. (“I will say, a Panamanian approached me recently and said they recognized my accent, so maybe Tati just has a Panamanian accent,” Fabrega adds.)

There’s a sense that Tati is a mysterious being who can be mutable for the sake of comedy. In season one, she reveals she can see through time and space, and season two suggests she’s hiding something very important, and potentially darkly powerful, in one of her purses. These mysteries give Tati, who is typically low status among the group, some mystique, but the details are kept purposefully vague. “What I like about Tati and Los Espookys as a whole is that there are a lot of unanswered questions,” Torres says. “The purse is a fun example of ‘There’s eccentric people everywhere, and you wonder about their lives, but you never get to find out.’” The pilot also suggests Tati is physically indestructible, but in the season-two finale, she manages to scrape her knee while riding a stationary bike. “Maybe it will come up in some way later,” Fabrega says, “but once the show got picked up, we were like, ‘Let’s not really cling to that.’”

Tati is close with Úrsula but maintains a somewhat distant relationship with the other members of the crew. That’s especially the case with Andrés, though the two have an unspoken understanding as people who occupy realities not consistent with anyone else’s. They often butt heads — bickering, for instance, over how they would decorate an imaginary egg — but occasionally have brief periods of détente. “There’s a sweet moment where she asks if he has a room where she could open her purse, and he says yes,” Fabrega says. “He understands this is important to her, and he’s going to respect that.”

“She should not look cool.”

As soon as Fabrega had the idea for the character, she knew exactly how she would dress her: not well. “When we first shot the pilot, the stuff our costume designer, Muriel Parra, had pulled for Tati was kind of cool, like Grimes was a reference for her,” Fabrega remembers. “I was like, ‘No, she should not look cool like the rest of them.’” Fabrega pushed for Tati to look consistently out of fashion. Parra sources her wardrobe — which consists of T-shirts, awkward-length shorts and capris, and sneakers — from thrift stores in Santiago, Chile, where the series films. “When I look for clothes for Tati, I never really know what I’m looking for,” Parra says. “They have to have humor in the pattern or in the details — maybe the buttons or some strange pocket. I only understand it when I see it in front of me.”

Crucial to Tati’s sense of style are her signature accessories, which tend to be childishly blunt, and she loves to make a statement with a hat, particularly the newsboy style. “There are two or three that she always wears,” Parra explains. “They have to be from the men’s section with a specific shape. There is not much change, as we must take care of the character’s silhouette. If we were to change the style of the hat, it would no longer be Tati.” Parra brings a similar approach to Tati’s purse, which the character carries high up on her body in a way Fabrega exaggerates by slumping her shoulder defensively. Parra finds the bags in vintage stores — purses from the ’90s fit Tati’s style, somehow — and goes for ones that are small with some “strange or exaggerated details.” (Even the design team doesn’t know what Tati’s hiding; as Parra puts it, “Everyone is so curious about what’s in the purse!”)

Tati’s silhouette changes only when she dresses for a specific role or job, and in those cases, she always goes for a striking transformation. Early on, Fabrega, Torres, and Armisen decided Tati gets most of her ideas about the way the world works from very basic pop culture, so that when she dresses up, she goes all out in the most recognizable way possible. “There’s a distinction between Tati being Tati and Tati imagining herself in another role,” Fabrega says. “She might look bad in her day-to-day life, but when she’s playing a character, she should somehow nail it.” Her date look is a faithful 1920s flapper costume, while housewife mode required a very feminine ’50s and ’60s style in the vein of Jackie O. During her divorce negotiations, Tati shows up in a slim pantsuit and lacy bra as if she were starring in a daytime soap. And at the end of the first season, she attends a wedding in a re-creation of J.Lo’s famous green Versace dress because, in her mind, that’s the fanciest possible look. “There had to be no doubt that it was J.Lo,” Parra says. “The clothing had to be tailored and perfect. Ana tried it on, we corrected some points, and that’s it! Tati did the rest of the work.”

“The lack of originality of our times.”

In the show’s second season, the creators set out to find an emotional arc that revolved around Tati’s need for validation. She starts by trying to have the perfect marriage to Juan Carlos; when that absurd arrangement inevitably falls apart, the writers determined Tati would go on a quest to prove herself as an independent woman. Thus, she embarks on a career as a writer based on her misconception that audiobooks are not the same as real books. “She sees the audiobooks and is like, If people love the audiobook, they’re going to love the book,” Fabrega says. Tati starts writing her own version of Don Quixote, chosen because it’s a classic Spanish novel (funnily enough, there’s also a Borges short story about a man rewriting Don Quixote, though the Los Espookys writers were not familiar with it), then goes on to write her own versions of Romeo and Juliet and One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Because Tati gets bored along the way, her versions of the books are invariably shorter than the originals and feature herself as a character. “All the books she writes end with everyone saying how much they respect Tati, a butterfly landing on her nose, and people clapping,” Fabrega says. “The books are her way to give herself the treatment she wishes she had in real life.” The books also look like Tati made them herself: “Ana wanted a very simple design, almost childish,” says Jorge Zambrano, the show’s production designer. “It fits with Tati’s whole aesthetic.”

Because Tati’s books are so cheap, they end up being massively successful, as schools start buying them instead of the original versions. “It’s like how on TikTok, some people will recycle audio from other people or lip-sync other people’s jokes and then go viral and make money off it,” Torres says. “Tati really sheds light on the lack of originality of our times and how people feel fulfilled by it.”

“An empty environment with a lot of magic inside.”

Tati’s success as a writer is a huge source of pride for her, and in the penultimate episode of season two, directed by Fabrega, she attends a women-writers’ panel dressed like Louisa May Alcott. She even brings a little bell so she can interrupt the other speakers. “Tati thinks of it as a game show,” Fabrega explains, but the character is soon chastened: The other panelists call her out for plagiarism, and she slowly begins to understand what she was doing was wrong. This is illustrated by a peek inside Tati’s mind: “I thought, What does learning look like for Tati?” Fabrega says. “So let’s go into her head.”

Inside Tati’s brain, a bunch of mini Tatis live in plain twin beds. There’s a generic black-and-white poster of the Eiffel Tower in the background and a pile of cables in front of the Tatis that represents the synaptic connections in her head. “The design of Tati’s mind is a little like where Andrés talks with the Water Shadow. It’s an empty environment with a lot of magic inside,” Zambrano says. Despite the room’s simplicity, the sequence was not easy to shoot: “It was a very intense day and very hot in the studio, and Ana had to do each version of Tati and also direct it.”

The image of the Eiffel Tower is, like many of Tati’s aesthetic choices, another received idea of what culture should be. It’s also a poster Tati has in her actual room, which Andrés sees earlier in the season. “To her, art is just pictures of Audrey Hepburn or pictures of the Eiffel Tower. Very generic,” Fabrega notes before pointing out that Tati has two puzzles of that same image on the floor, both missing the same piece — the perfect illustration of how Tati’s brain works.

Once the mini Tatis get their synapses clicked together, full-size Tati realizes her endeavor is unethical and throws herself into her work with Los Espookys, completing her arc for the season by getting a little respect from her colleagues. In the final episode, they engineer an eclipse so that a presidential candidate can adjust her tube top in the middle of her speech without people noticing; Tati peddles a stationary bike that powers the gears of a contraption connected to a giant papier-mâché moon. When their ruse is successful and people start clapping, a butterfly lands on Tati’s nose — a moment added in visual effects. “I don’t know if people will catch it,” Fabrega says, “but Tati thinks the people are clapping because the butterfly is landing on her nose, like in the books.”

As for the as-yet-unconfirmed next season, the writers hint that there’s still much to learn about Tati. “Maybe Tati is just so homophobic,” Torres adds. “Maybe she’s fiendishly conservative in a way that you’re talking to someone you know from work and suddenly they say something and you’re like, Ohhh, and you just sort of have to move on.”