From certain high perches in Henderson, Nevada, where made-to-order modernist mansions bloom across the terraced mountain ranges, the city of Las Vegas unfurls below you like a magic carpet. On a recent fall afternoon, Usher Raymond IV, the 45-year-old artist known the world over simply as Usher, took in the view from the head of his outdoor dining table, his goldendoodle, Scarlett, asleep at his feet. “When is the last time you looked in a mirror and really looked at yourself?” he asks. That morning, I say. “When you looked in that mirror, did you tell yourself you loved yourself? Did you tell yourself that you forgive yourself?” Reader, I had. But only because when we spoke the prior afternoon Usher had suggested it. “I did, too, this morning,” he says, with a flash of his famous megawatt grin. “It’s a little psyched-out to say this, but it made me feel good. I was like: You need to look at yourself and say: Hey, whatever you’re dealing with, I love you.”

Here’s what Usher is dealing with: the physical demands of a so-sold-out-they-extended-it-twice Las Vegas residency (Usher: My Way, The Vegas Residency) for which, three nights a week, until December 2nd, he would be almost constantly singing, dancing, and occasionally roller-skating, all through an R&B fantasia, replete with exotic dancers, a peach-shaped disco ball, and several costume changes and elaborate set pieces. (Not unrelatedly, he has a bunion that requires surgery.) He’s also recording a new album, Coming Home, his ninth, all while planning the 2024 Super Bowl halftime show, the biggest single televised moment of his career. He’ll be maintaining this momentum past the show, he tells me, and seeing his therapist and doing his daily meditation practice and working out and eating right and being a good partner and raising four children, two of them under the age of four here at this sleek five-bedroom home his family found for the Vegas run.

Usher doesn’t sleep much. The day before, as we drove together between Vogue shoot locations, he got quiet thinking of the pressure. “I know that it’s going to be the hardest time of my life,” he said of this period of performing, planning, singing, skating, training, promoting, parenting, being present. But one thing about Usher is that he knows about the power of love.

You have never met someone so loved as Usher. And I don’t just mean in his music, though love is more often than not its subject. I don’t even mean just at home, though his partner of four years, Jenn Goicoechea, and their two children, Sire and Sovereign, as well as his Atlanta-based teenage sons from a prior marriage, Usher “Cinco” V and Naviyd Ely, certainly have that covered. I mean in the larger sense—the global sense. At his Vegas shows, the energy inside the (typically 85 percent female) audience is probably best described as affectionately feral. Everyone wants to love him down, but they also want to love him up. When I attended the show in March, during one of Usher’s crowd-work sections, a demure-looking audience member attached herself to Usher’s chest, seat-belt-style, from behind, locking her hands across his sternum until her eyeglasses got misty. (He allowed it for a few bars with a kind “okaaay,” before gently removing himself.) Seven months later, at a show in October, a few songs after one audience member leapt into the aisle in an attempt to grind (another kind “okaaay”), a woman in the front row alerted him, nursery-school-teacher-style, that one of his shoes had come untied. He knelt and fixed it, crooning with the same grin as before. Not a soul alive wants to see Usher fall.

Sure, you’re probably thinking, lots of big stars are loved. That’s why they’re big stars. And plenty of them behave badly and retain deep banks of parasocial fan armies to rise to their defense. This is not like that. Usher has dedicated, dyed-in-the-wool fans—though not quite enough of them to save him from a mid-career dip in the late aughts, around the time his fifth album underperformed and it felt like music en masse was moving away from his brand of R&B. (That dip, by the way, has ultimately made people love him more: how did we forget about Usher?!) It’s the people who work with him every day who make you feel how much he is loved—his manager and bodyguard and assistants who sit you down and tell you what a good guy he is; the Dolby theater ushers who work the show three nights a week, joyfully singing along to all of the songs; the other R&B superstars who turned up as surprise acts (Nas, Jermaine Dupri, Teyana Taylor, Keyshia Cole, Anita Baker); the boldface names who turned up just to turn up (LeBron James, Zendaya and Tom Holland, various Kardashians, Jennifer Lopez, Doja Cat, Issa Rae, Keke Palmer). There are designers, too, like Bianca Saunders, who attended the 2023 Met Gala with him, driving through the streets of New York in the matte-black 1960s Cadillac convertible he imported to the city for this purpose. (He was a perfect date, she tells me on a call from London, and let her control the radio.) Or Balmain’s Olivier Rousteing, who designed Usher’s wardrobe for the first stretch of his Vegas residency. “Usher is just so humble and so kind and so generous,” Rousteing tells me. “I’ve been really lucky in my life to have met incredible artists, but Usher is definitely one of my favorites to work with, because he’s so nice.”

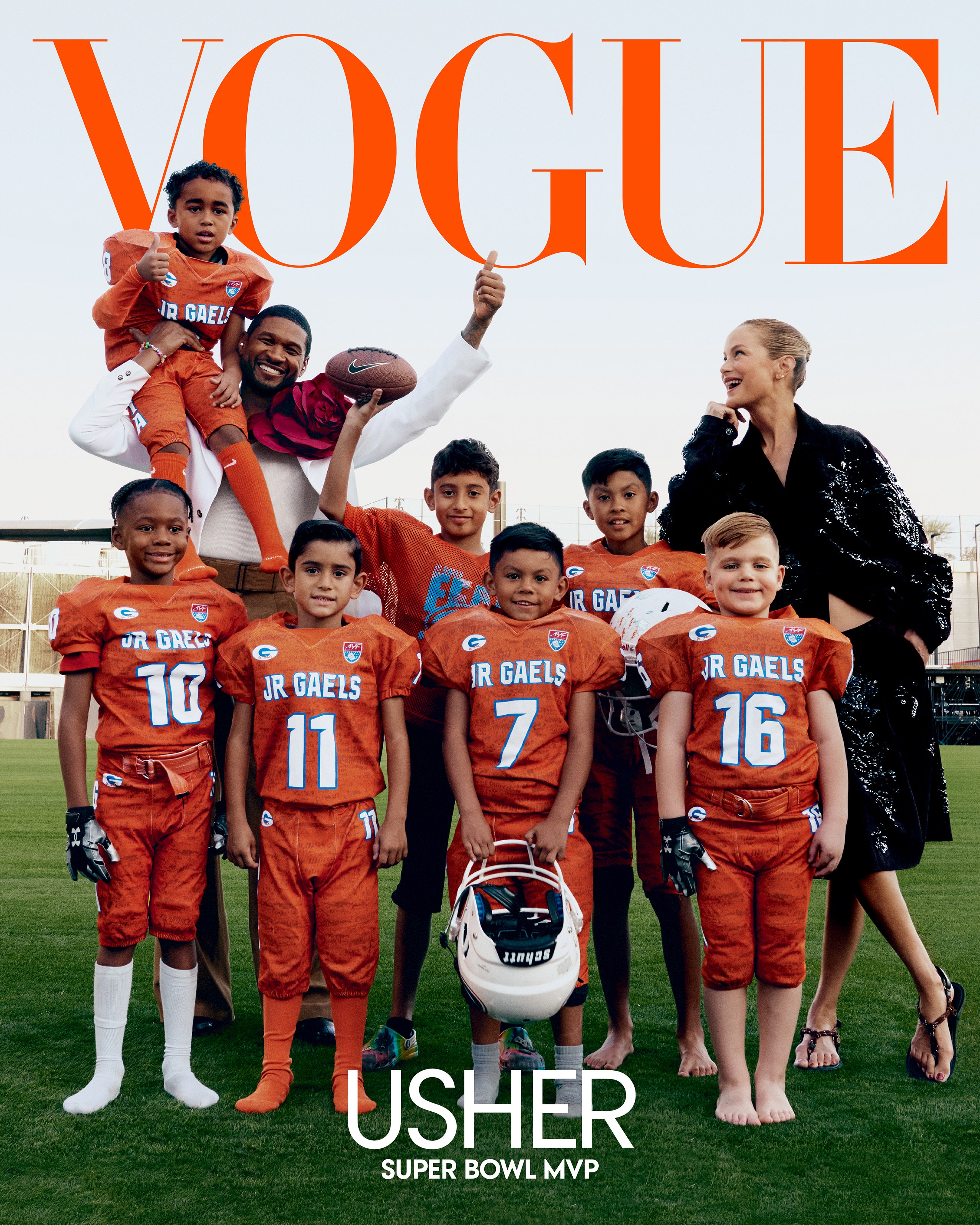

Usher’s longtime barber Shawn “Shizz” Porter refers to Usher’s stage presence with words like ordained. “You should have a spotlight every day of your life!” he shouts as Usher serenades model Carolyn Murphy for Vogue. Murphy, aglow, fans herself after the shoot: “I have the best job in the world.” (Later, Murphy carried the fire-hydrant-size arrangement of hydrangeas Usher had delivered to her dressing room with her to dinner. “What a gentleman, truly a rarity,” she said. She saved the accompanying note for her scrapbook and planned to show it to her daughter, Dylan, back home in LA. “So she’ll think I’m cool.”) Vogue’s photographer Campbell Addy says he knows every Usher song: “I used to buy the CDs and just study the lyrics in the liner notes. Come on: It’s Usher.” Sure, there was that late-aughts ebb, but now there’s just so much flow. “Every night I walk out and I’m present before I walk on the stage,” Usher says the next day at his house. “Maybe no one else knows that I’m doing this, but I’ll walk over to the edge of the stage and I look up there.” He angles his head up at the invisible fans in the invisible rafters, a blur of happy screams and sparkly outfits who dance and selfie and party the night away as if life begins and ends at the Dolby theater at the Park MGM, “and I can remember when nobody was in here, and it was hard, and it felt like nobody was going to come. But I see them having a great time and I’m like, Here it is—” There’s that million-dollar smile. “Honor that moment. Now go have a good time.”

When we meet, Usher has just been handed the key to the city (October 17 is now officially Usher Raymond Day in Las Vegas), though by the looks of his social media tags that month, he seems like the prince of Paris. He’d put on a 12-day residency at La Seine Musicale—a Paris version of the Vegas performance (attended by Pharrell, Christian Louboutin, and Gabrielle Union and Dwyane Wade, among others) that synced up in time with the shows, and so he’d gone to some (Valentino, Chanel, Marni, Balenciaga), as well as various dinners and galas, all dressed in the season’s best. He sort of stole the show, I tell him. He shrugs, faux-demure. (Usher doesn’t brag.) “You know you were a hit,” I nudge. “It worked,” he grins. It sure did: Rousteing compares his talents and cultural weight to that of Michael Jackson or Prince. “I think he’s one of the few artists that knows how to play with a wardrobe and feel confident enough to push boundaries and have his own style and his own identity without trying to be someone else,” the designer says. “When he came to my show for the first time in 2020, I was crying. It reminded me of when I was younger and unknown and dancing to his songs, and I was just like, Wow, this is such a big thing to have Usher here in this room.”

Fashion has always been important to him, Usher says. He grew up in Chattanooga, Tennessee, with a mother and grandmother who took great pride in the way he and his brother dressed for church. “I think my mom, she really strived to make certain that we always looked well put together,” Usher says, “and that we understood the importance of Sunday, but more than anything we understood the idea of putting something on that made you feel better, that made you feel good, feel special.” He’s drawn on those early style codes—the perfectly tailored suits, the ultra-shined shoes, the posture, the effort—his entire life, along with some glamour and glitz from the music world: Berry Gordy, Teddy Pendergrass, the Commodores, Lionel Richie. “He’s suave,” says Saunders, and it’s worth noting Usher also cites a dash of debonair Paul Newman, Burt Reynolds with his exposed chest and Porsche sunglasses, and Gene Kelly’s grace and athleticism as part of his style ethos. “I always present myself as a gentleman,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be super dressed up, but you know, tailored, and making sure there’s some thought.” Usher never wants you to think that he doesn’t care about the way you see him, or the way that he sees himself.

These days he finds himself using the rare quiet moment to think about what he might do next. His own clothing line could be in the cards. It’s on a list of possible post-residency endeavors whose common theme is that they don’t require him to sweat it out on stage for three-plus hours, three nights a week: “I love it, don’t get me wrong,” he says. “But man. Shit. I’m not looking to be 60 years old up there.” That list of possible next projects? It’s not short. He’s a collaborative guy who doesn’t much like to sit still. “I was the kid who never wanted to stop,” he says. “I still am.” Las Vegas isn’t exactly home—that’s Atlanta, where he’ll likely return after this stretch is over—but he’s not done with it. The city did more than throw open its doors and provide a stage for him; it became a kind of incubator. He arrived in 2021, and they showed him the Colosseum at Caesars and just said dream, he tells me. And he did, through the end of that first sold-out residency and over to a new one at Park MGM, and suddenly more was happening, like his NPR Tiny Desk Concert, of all things, where his charm nearly broke the internet, and more of those sold-out shows and the adoration poured in, because maybe we’d forgotten just how good those songs were, and how many of them there are, and how great he was at performing them. And then Jay-Z called up to tell Usher he wanted him to do the Super Bowl, and he decided to whip up a new album, his first in six years, set to debut three days prior (Feb 9th). It’s no wonder we’re wondering what he might be dreaming next.

First, he’s got to clear the Super Bowl–size hurdle of the next few months. “Every day I’m kind of sitting here and I take a moment to just look at where we’re going to be, which is right there,” Usher says, pointing out the shining black glass oval of Allegiant Stadium from his seat at the table. The halftime show is famously just 13 minutes long, with eight minutes only to set up the stage, and zero room for error. “It has to be perfect,” Usher says. Thirteen minutes is not a very long time for someone who likes to dazzle with interactive experiences and elaborate set design, for someone with several decades of hits and a deep bench of collaborators. “I’ve been doing this for 30 years,” Usher says. “I want people who have been a part of that journey to feel like it’s a celebration for everybody, for all of us, from the beginning up until this point.”

The specifics are still under wraps, but in mid-January, during a break on the Bel Air set of a glossy new music video for an afrobeat-inflected earworm off Coming Home (20 tracks of absolute bangers, by the way, that will make fans of his oeuvre exceptionally happy), Usher sits down to share a few hints about halftime. Yes, there will be skating, and the killer choreography you might have come to expect; there will be at least one major costume change; and perhaps most pivotally, there will be some important guests. “This night was specifically curated in my mind to have R&B take the main stage,” he says, and he’s pulled together people who represent, for him, the genre’s architects. “Not just R&B music, but R&B performance, R&B connection, R&B spirit.” He’s been thinking about legendary Vegas showmen like Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley while diving deep into the details—he's dedicated to the minutiae of his performances, he says, but he’s been working on “letting go." It has to be a perfectly orchestrated and (much rehearsed) 13 minutes that also has to be approved by the NFL, but he promises that the audience will feel that they are personally being serenaded. “I’m literally speaking to every woman,” he says, “I want to make it feel like that.” It will be a celebration of everything he’s done and everywhere he’s been, and it will sit comfortably with the iconic performances of Super Bowls past. He’s been thinking a lot lately about Michael Jackson, and Prince, and what R&B represents in a country where it wasn’t so long ago that Black performers like him had to walk through the kitchen in order to be on the stage. “I’m thinking about the fact that I’ve been able to walk through the front door as a result of their sacrifice and ability. So I’m carrying a little bit of that,” he says. “It’s made me feel joyous. It made me feel like I want to go out there, and I want the world to smile when they look at me. I want them to feel something, and feel my passion, my love, feel like I was the right person to sit in this position, and I was the right person to bring this kind of energy and love and connection to the entire world.” Not just because of the songs, or the hit records, but because of him: that famous onslaught of love shaking Vegas one more time. “People will tune in for a football game, but I hope when they look at that halftime performance, I'm hoping they walk away with something that’s healing them,” he says. “Something that makes them feel hopeful, and not just look at the past, but have hope for the future, and have hope for a different type of future than we’re looking at right now in the present.”

In Henderson, from where he sits, he can see the city, the Strip, the surrounding Mojave Desert. He sees the blank spots, the places that might benefit from a little of Usher’s investment, his strategy, his way of approaching life. The view puts him in the mood to think about building. Is it about investing in the underserved local communities, giving them places to go, and learn, and be healthy, be creative? He could build a restaurant or a boutique hotel, or do something with the style of immersive theater that he loves, experiences that require people to get off their phones and be present, to lead them back to that mirror, back to themselves. It’s all still on the table, once he gets the next few months off his plate. It’s a bit like he’s Superman in his Fortress of Solitude, strategizing how to save Las Vegas, I say. He slides down in his seat and taps his fingers together in front of his nose, mastermind-style. “I’m a dreamer, man,” he says. “I am about the fan experience, trying to figure out how to give them something that’s going to make them feel something, make them feel like they had a piece of it, you know?”

He straightens up and looks at the city skyline again, hanging like a mirage over his swimming pool. Scarlett has wandered over to nap in the sun. Sire and Sovereign are inside trying on their Halloween costumes (Mario and Princess Peach). His chef wants to know if we’re hungry. Jenn apologizes but reminds us that he’s running behind, he’s got a day full of meetings and another show to prepare for tonight. The Usher universe whirls onward and upward. “You know, everybody’s always talking about my being the king of something,” he says, and they are, traditionally of R&B, more recently of Las Vegas. “I’m not invested in that. I thank you, I thank you very much. That means I work really hard to be the king of something,” he says, turning back to look at me, making sure I really see. “But a kingdom. That is going to last longer.”

In this story: For Usher: hair, Shawn “Shizz” Porter; makeup, Lola Okanlawon. For Carolyn Murphy: hair, Evanie Frausto using Bumble and Bumble; makeup, Raisa Flowers.