Q&A conducted by Laura E.P. Rocchio

Tony Willardson

Executive Director

Western States Water Council

Tony Willardson has been thinking about water for a long, long time.

Since joining the Western States Water Council as a research analyst in 1979, he’s worked his way to become the executive director of the waterwise Council. Along the way, he’s seen many concepts for staving off water shortages in the U.S. West, from ultimately untenable large-scale water transfers (like one idea for transferring water from Alaska’s Yukon) to an array of conservation incentives and technologies.

But one concept has stood out among the rest for its versatility, fiscal feasibility, and broad scale relevance: the use of Landsat satellite data to accurately calculate field-level water use.

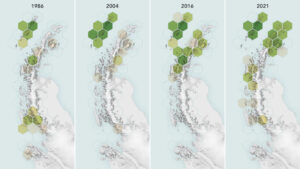

Landsat, with its medium spatial resolution, measurements made across the visible and infrared spectrum, bi-monthly or better data collections, and rigorous calibration, is uniquely suited to monitor something called evapotranspiration, or ET. ET estimates capture the combined amount of water that is lost to the atmosphere from evaporation from soil and transpiration (think sweat) from plants. Water lost to the atmosphere is water consumed—it does not return to the local water system.

So, ET, in effect, is an estimate of consumptive water use.

In the U.S. West, water rights are determined by seniority (who used the water first) and “perfection” (how much water has been consistently and beneficially used over time). Senior perfected rights are valuable vested private property rights, so accurately tracking consumptive water use is paramount.

Among Landsat’s many spectral measurements, it is the thermal infrared band that is most integral to ET calculations; the relative temperatures of agriculture fields show the energy balance flux that is driven by ET.

When the thermal infrared measuring capability—and thereby its ability to measure consumptive water use—was eliminated from the planned Landsat 8 satellite in the early 2000s, Willardson and the Western States Water Council (WSWC) joined with western governors and western U.S. Senators to communicate what that loss would mean for water management in the West.

A thermal infrared sensor was subsequently funded and added back onto Landsat 8—maintaining the thermal record begun by Landsat 4 in 1982.

Since that time, Landsat has only grown in importance for western water management with the advent of OpenET for easy access to Landsat-based water consumption estimates. Recently, a 2023 pilot study by the Upper Colorado River Basin used OpenET to determine how much water farmers might choose not to divert and to leave in local streams as part of a voluntary, temporary, compensated conservation pilot program. An estimated 37, 810 acre-feet (~12.3 billion gallons) of water was conserved at a cost of just under $16 million.

And over the last decade, the WSWC has worked with western governors to build a water rights database that includes data for 2.5 million water rights across its 18 member states. A new tool is now being developed by the WSWC that combines that database with OpenET information to promote water conservation in the West and facilitate the transfer of water from one use to another on a voluntary basis.

With Landsat-based ET embedded in more and more water rights and conservation tools, Willardson and the WSWC are eager to see Landsat Next with its higher spatial resolution, more frequent observations, and additional spectral bands, built and launched. Willardson penned a letter to NASA and the Department of the Interior in August 2024 sharing that sentiment.

Talking with Tony

Willardson is a person who exudes goodwill. His kind nature is almost palpable, and there’s a glint in his eye that conveys the energy of the possible. We had the opportunity to speak with him recently about Landsat’s role in western water management.

Here are highlights from our conversation:

The Western States Water Council has been advising U.S. Western Governors since 1965 on water policy issues. When did the WSWC become aware of Landsat—and its thermal data—for managing water?

Our involvement with Landsat began in 2005 when we wrote the then-NASA administrator Michael Griffin, as well as NOAA, and USGS about our interest in the Landsat program.

Landsat had been brought to our attention by the state of Idaho. Their Department of Water Resources had been using Landsat as a primary method to measure consumptive crop water use.

It didn’t take much imagination to understand the potential of the tool, given that 70–80% of water use in the West relates to agriculture and there has not been—and still isn’t—a great way to directly measure that water use.

Idaho had really invested in the thermal data from Landsat 5 and Landsat 7 and had built their business processes around that information. And soon after that, I think by 2008, there were at least 10 western states using thermal infrared imagery in some manner to manage their water resources.

When NASA dropped the thermal imager from Landsat 8, that was a concern—particularly in Idaho. So, they raised the issue with the Council.

In a letter to NASA and DOI, you recently wrote:

Landsat is the only operational satellite having both thermal data and a spatial resolution fine enough to map water-resources use at the level of agricultural fields.

How would you describe the impact that Landsat has had on data availability for water managers and timely information for decision makers?

Landsat has been a catalyst for innovation in administering water rights. Now we can be much more precise in measuring and monitoring and then administering rights.

Landsat is on a field scale. The resolution can be at a field scale, which has been very important so you can look at the individual fields or a crop circle and look at differences in use across that field. Or you can look at it across the whole state of Nebraska.

Why is Landsat data continuity and the launch of Landsat Next important in the eyes of the Western States Water Council?

It is critical given the situation in the West. While we’ve had a couple of good years recently, that follows 22 years of drought. We’re not going to see a lot of development of new water sources. Many streams are over appropriated and groundwater aquifers too. The climate hasn’t been cooperative. So, we’re going to face shortages more and more in the future. We’re going to have to make do with what we have and that’s going to require marketing and trading. Landsat lets us more carefully measure and monitor what is being used according to the rights.

That is why we are so interested in maintaining the capabilities on Landsat Next.

Landsat Next will provide continuity and improvements like a shorter return time and a finer resolution that I think is really going to benefit users in the future.

And, it is not only that it is valuable to us. It is something that’s used worldwide.