Fertility has become a major target for regenerative medicine. What if, the thinking goes, science and medicine could be used to simply restore fertility to women who for one reason or another no longer have it? In mice, scientists have now done just that.

In a new paper out Tuesday in Nature Communications, scientists at Northwestern University report that they successfully removed a mouse’s ovary and replaced it with a 3D-printed one made from its own ovarian follicles. What’s more, using those bioprosthetic ovaries, the mice were able to ovulate just like normal, mate, give birth to healthy mouse pups, and even nurse them.

“The idea would be that a young cancer patient who has to undergo chemotherapy would have an ovary taken out before the first sterilization treatment, that tissue preserved, her ovarian follicles isolated and then when she’s ready we could give her a new ovary,” Teresa Woodruff, a reproductive scientist and director of the Women’s Health Research Institute at Northwestern told Gizmodo.

But that’s not even the coolest part. In recent years, other scientists have actually pulled off this feat in mice using 3D-printing a few times. But human ovaries are a lot bigger and more complicated than mouse ovaries, and there has been concern that the material and method of constructing the ovaries wouldn’t hold up if you tried the same thing in people.

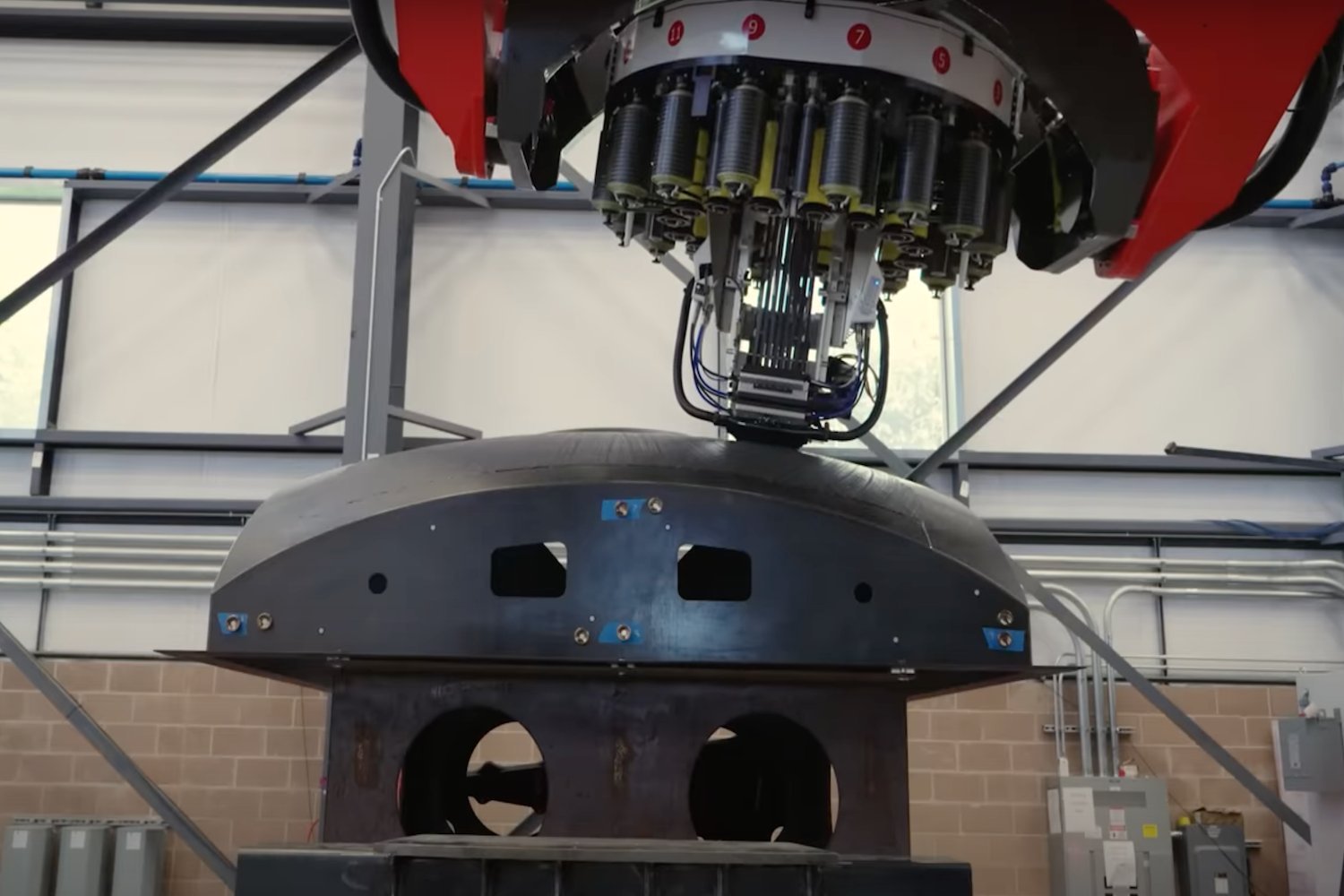

“Our real advance here was to use gelatin, a biomaterial that makes up most of our soft tissue, and make an ovary proxy,” said Woodruff. “That’s going to be important for the whole field of tissue engineering.”

Woodruff and her team were able to make a structure that was rigid enough to stand up to surgery, but also porous enough to work with the mouse’s body tissues. They also found that the pattern in which the new ovary was printed had a significant impact on whether the ovary prosthesis actually worked.

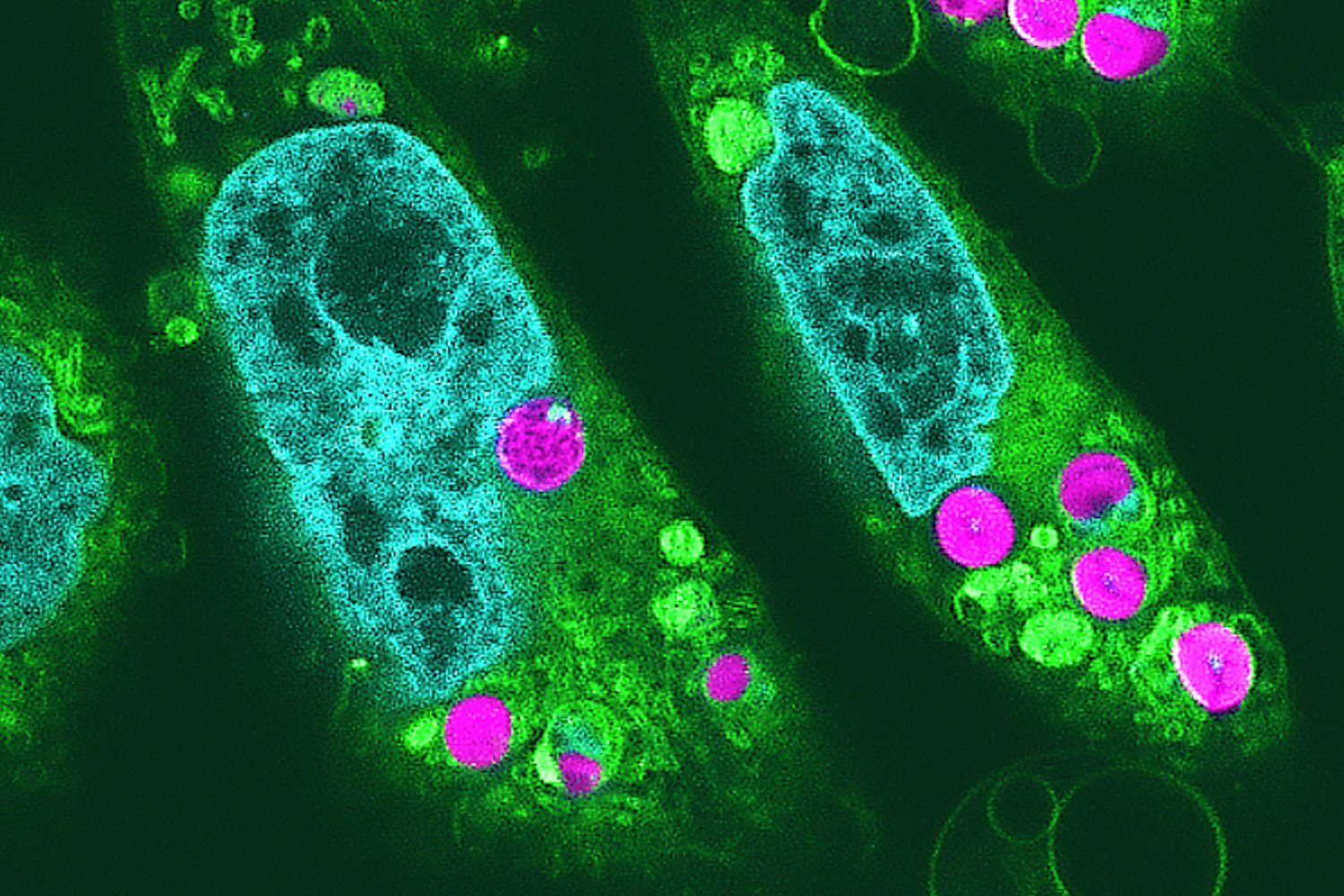

Here’s how it works: Scientists removed mouse ovaries in order to sterilize them, then preserved the ovarian tissue and isolated its hormone-producing cells that support immature eggs. Using a 3D-printer and gelatin, they then printed the basic structure of the ovary, and dosed it with the cultured ovarian follicles. These ovaries were then surgically transplanted back into the mice, where their egg cells then began to mature and ovulate. Blood vessels formed that allowed hormones to circulate within the mouse bloodstream to take care of all the other parts of pregnancy, like lactating after birth.

And eventually, the mice gave birth to pups. The pups were also engineered to glow, as a way to keep track of which ones were born from mothers with the bioprosthetic organs.

Woodruff said that the ultimate goal was not just to allow women to get pregnant, but to restore the total health of a woman’s endocrine system.

“Some people just think of the ovary as fertility,” she said. “But it’s more than that. It’s part of the overall system of a woman’s health.”

There is a lot of interest in using cutting edge technology to restore and improve fertility—and a lot of crazy plans for how to do it. Woodruff’s work, though, may be one of the most realistic approaches yet. Already, it has been proven to work in mice several times over. At this point, much of what’s needed is hammering out the details of how it will best translate to people. Woodruff hopes to address some of the challenges—like finding a method of printing that creates the best chances of the egg cells maturing, and a material that will create a durable organ that lasts in humans.

Woodruff’s lab has been on the hairy edge of fertility technology several times over. Earlier this year, her lab use tissue cultures to create a miniature 3D model of the female reproductive tract, a “period in a dish.” And they have successfully grown immature egg cells into mature ones in a lab. Federal funding rules have prevented her from taking that research any further and fertilizing the egg to see how it continues to develop, but she’s seeking non-government funding to continue it.

The lab’s work will next be tested in pigs, and there is a fair amount of work to be done before its ready for humans. But, Woodruff says, that won’t be too far in the future.

“This is less than 10 years away people,” she said. “We’re just not there yet.”