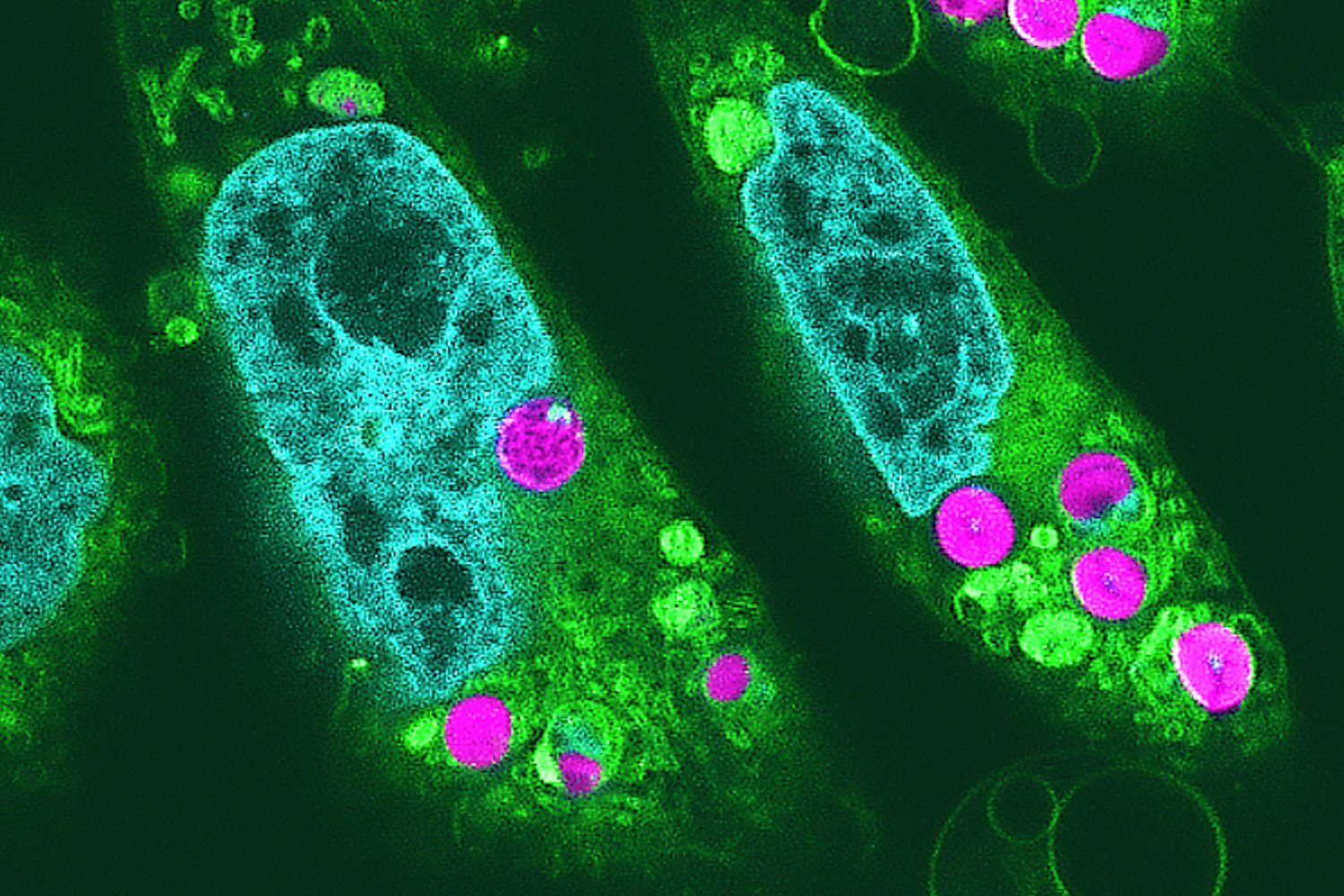

Scientists created this picture of the Mona Lisa using genetically modified E. coli bacteria. Such teeny little artists!

The Italian researchers weren’t just playing around with bacteria for fun. Rather, they were attempting to unite different attributes so they could control large populations of bacteria—perhaps to one day build microscopic transport devices, or even 3D print using bacteria.

“I think it’s an interesting proof of concept of possibly using bacteria as bricks to build structure on the microscale cheaply and easily,” study author Roberto Di Leonardo from the Sapiezna University of Roma told Gizmodo.

Evolution has produced lots of cool survival strategies, but all those traits don’t appear in the same organism. You know, fish are kind of dumb, but they can breathe underwater, while humans are less dumb but unfortunately susceptible to drowning. In this case, the researchers were interested in uniting the light-sensitive protein proteorhodopsin—basically a solar panel for cells—with the E. coli’s flagellum, a tiny tail motor. They hoped to create a system where the more light a bacterium received, the faster its tail would move.

The researchers spliced the proteorhodopsin-producing gene into the bacteria. Then, they replaced a projector’s lens with a microscope lens in order to project images onto a stage that held the bacteria, two micrometers per pixel. The researchers knew that slower-moving bacteria receiving less light would clump together, while faster-moving ones receiving more light would move farther apart. The clumping patterns would create the resulting image, where regions of more bacteria appear white and regions of less bacteria appear black. The researchers shone negatives in order to create the images.

There were still some issues, according to the paper—bacteria were slow to change positions, and the images came out fuzzy. So, the researchers set up a feedback loop where every 20 seconds, the bacterial positions were compared to the final desired image. Places where the bacteria over-accumulated were brightened to speed up and spread out the bacteria, and places where the bacteria under-accumulated were dimmed to slow down the bacteria and cause more clumping.

The researchers point out that there are other passive systems in which genetically modified bacteria selectively stick to surfaces. But with motion, bacteria assume their positions quicker.

Christina Agapakis, creative director at Ginkgo Bioworks who was not involved with the study, was impressed by the work. “This rules,” she told Gizmodo.

Will light-reactive bacteria ever power microscopic machines or become 3D-printed, living, functional bricks? Time will tell. but for now, they’re recreating the Mona Lisa.

[eLife]