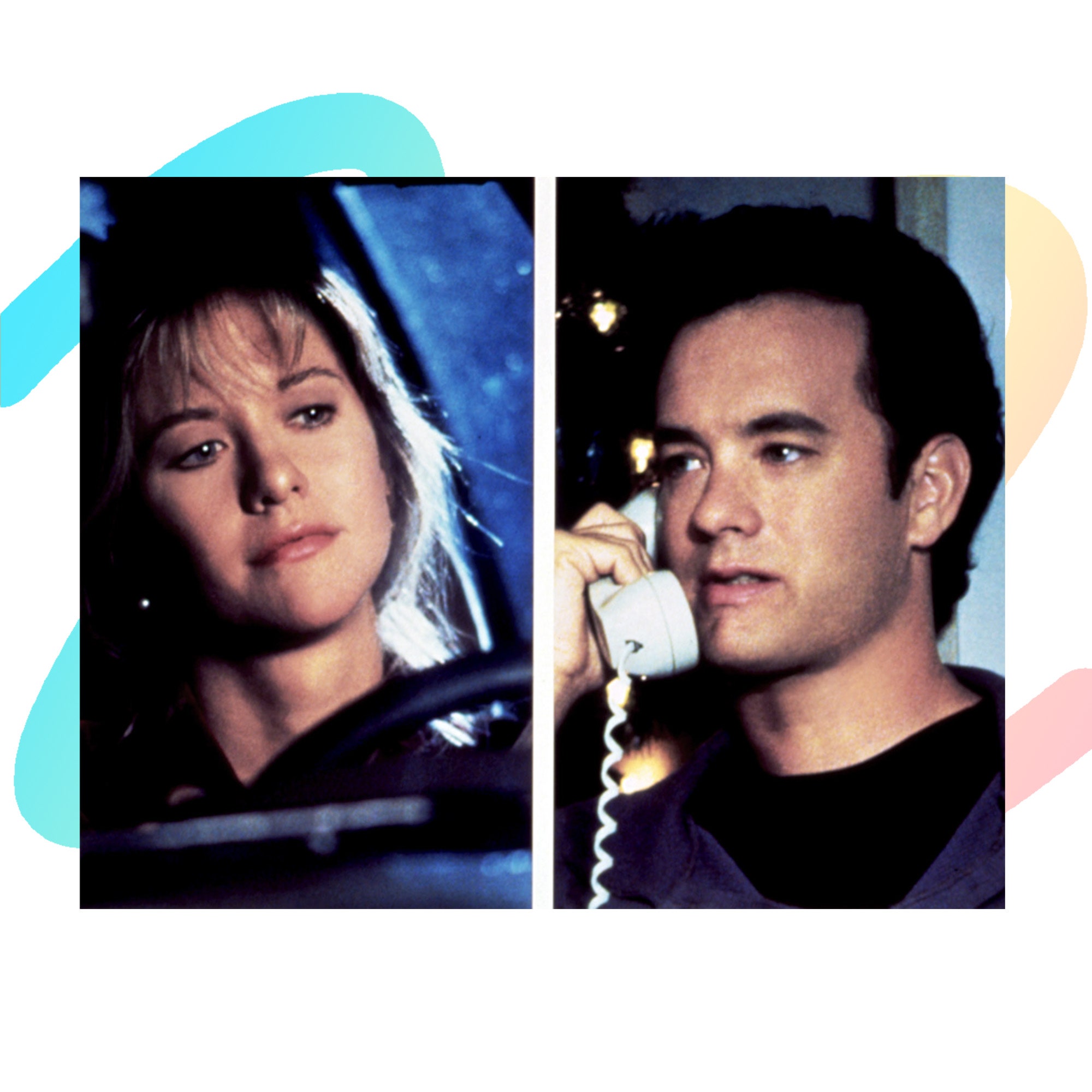

“Shall we?” Tom Hanks’s Sam asks Meg Ryan’s Annie, lifting his hand toward hers as a slight breeze blows and the music swells. The Seattle widower and Baltimore journalist finally meet—where else—atop the observation deck of the Empire State Building on Valentine’s Day, as Sam’s son, Jonah (Ross Malinger), looks on adoringly. This is only the start of their romance, but it’s the end of Sleepless in Seattle, released 30 years ago and now remembered as one of the best romantic comedies of all time.

Unfolding during the typically dreary period between Christmas and Valentine’s Day, Annie and Sam’s cross-country meet-cute begins with a Delilah-style radio show, which Jonah calls into with one request: find a new wife for his father. At one point, Sam gets roped into joining the call. Once on the line, he heartbreakingly describes the moment he fell in love with Jonah’s mother. “I knew it the very first time I touched her,” he says. “It was like coming home, only to no home I’d ever known.” Thousands of miles away, Annie is one of many listeners entranced by the story, maybe by the mere sound of Sam’s voice. A journey to meet him ensues.

“You don’t want to be in love. You want to be in love in a movie,” Annie’s best friend, Becky (Rosie O’Donnell), says—both a warning to the character and summary of why Sleepless in Seattle, directed by Nora Ephron from a screenplay by Ephron, David S. Ward, and Jeff Arch, endures three decades later.

Nominated for two Academy Awards and one of the highest-grossing films of 1993, Sleepless is the kind of movie that both comforts and confounds. “What if someone you never met, someone you never saw, someone you never knew was the only someone for you?” its tagline reads, a premise as fitting of a horror film as a romance. Repeat viewings lay bare the movie’s small pleasures—a kid-aged Gaby Hoffmann booking Jonah’s flight to New York, Rob Reiner explaining new-fangled ’90s dating to a stupified Sam—but can also leave the viewer dazed. As Roger Ebert wrote in his review, “Sleepless in Seattle is as ephemeral as a talk show, as contrived as the late show, and yet so warm and gentle I smiled the whole way through.”

Writer-director Nora Ephron, who sandwiched Sleepless in between 1989’s When Harry Met Sally and 1998’s You’ve Got Mail, understood the mix of sour and sweet required to get one love-drunk. According to film producer Gary Foster, Ephron was hired as “a slightly cynical New Yorker who was looking to put a little edge in the fairy tale.” As Ephron told Rolling Stone in 1993, she was merely “looking for a cash infusion.” But she had her directive in mind, once declaring of the film: “Our dream was to make a movie about how movies screw up your brain about love, and then if we did a good job, we would become one of the movies that would screw up people’s brains about love forever.”

In Ephron’s hands, the script was imbued with her biting East Coast wit, including a pre-Seinfeld “Soup Nazi” reference. (At one point, Annie enters her office at The Baltimore Sun to hear the tail-end of a coworker’s pitch: “he’s the meanest guy in the world, but he makes the best soup you’ve ever eaten.”) There’s also the following interoffice exchange:

Coworker: It’s easier to be killed by a terrorist than it is to find a husband over the age of 40.

Annie: That’s not true.

Becky: But it feels true.

(Sidenote: there’s a very similar riff on this joke in 2006’s The Holiday, made by Nancy Meyers, the Pepsi to Ephron’s Coke.)

But it also retained the genre’s unabashedly romantic DNA. By the time Ephron, the film’s fourth attached writer, got to the script, 1957’s An Affair to Remember had already become a character in the movie, much to Ephron’s chagrin. When she first watched the Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr–led romance, “I was a hopeless teenage girl awash in salt water,” Ephron told Rolling Stone. As an adult, she continued, “I now look at this movie and say, ‘What was I thinking?’” She got downright disdainful about it in another interview, calling Affair a “weepy” film that appeals to “one’s deepest masochistic core…. It’s really kind of hooking into those pathetic female fantasies.”

Ephron realized that the only way to comment on the expectations elevated by movies like An Affair to Remember or 1939’s Love Affair, was to write a movie just like them. “We’re trying to have our cake and eat it too,” she told Rolling Stone. “We’re trying to be smart, sophisticated, and funny about movies like this, but we want to be one too.”

That’s never more clear than in the scene where Rita Wilson (Hanks’s real-life spouse plays his character’s sister in Sleepless) summarizes An Affair to Remember in tearful detail. “There’s no reason for it,” Ephron would later admit. “It doesn’t move the plot along. You just can’t imagine the movie without it because it is what the movie it is.”

But unlike more recent romantic comedies, Sleepless doesn’t condescend to its audience or turn its nose up at the notion that movies warp matters of the heart. “Marriage is hard enough without bringing such low expectations into it,” Annie’s sidelined fiancé Walter (Bill Pullman, who got his due as Sandra Bullock’s one-and-only in 1995’s While You Were Sleeping) says during their frills-free breakup. Better to reach for the stars than settle for scraps, Ephron believed. “We all have unrealistic expectations,” she said, “but that’s no reason why we shouldn’t be in love in some way that feels important and magical.”

That combination of sentimentality and skepticism makes Sleepless sing. At the start of the movie, both Annie and Sam have sworn off idealism for different reasons. Sam had that kind of love with his late wife, Maggie (Carey Lowell), a type of magic he believes couldn’t happen twice. And Annie merely rejects the stuff, settling for safe with poor, well-meaning, allergy-prone Walter. “Destiny is everything we invented because we can’t stand the fact that everything that happens is accidental,” Annie says within the same movie where she ends up stalking Sam and Jonah both on the internet and in real life.

It’s that very transformation—a surrendering of reality in service of the intangible—which propels Billy Crystal toward that New Year’s Eve party, hoists that boombox above John Cusack’s head, gets Julia Roberts to ask Hugh Grant to love her, and yes, pull Annie and Sam toward the same New York City landmark despite having never spoken a word to each other. As Ephron told Rolling Stone, “There’s no one who’s more romantic than a cynic.”

Thirty years after that hallowed meeting, Sleepless can still charm optimists and nonbelievers alike. And although it’s clear that Ephron knew all—from the importance of a good salad dressing recipe to Deep Throat’s identity—she once laughed off her potential legacy as “a queen of romance,” telling Rolling Stone, “What a hilarious notion that it would be me!” But destiny, as it often does, seems to have intervened.

Presenting the 31st Annual Hollywood Issue

The 2025 Hollywood Issue: Zendaya, Nicole Kidman, and 10 More Modern Icons

Glen Powell’s Secret: “I Try to Think Audience First, Rather Than Me First”

Zendaya on Acting With Tom Holland: “It’s Actually Strangely Comfortable”

Nicole Kidman Talks Babygirl, Losing Her Mother, and a “Terrifying” New Role

Dev Patel’s Long-Ranging Career, From “the Little Rash That Won’t Go Away” to Monkey Man

Sydney Sweeney on Producing and Misconceptions: “I Don’t Get to Control My Image”

Zoe Saldaña Won’t Quit Sci-Fi, but She “Would Like to Just Be a Human in Space”

A Cover-by-Cover History of Hollywood Issue