With the release of Windows 10 RS5 the generic UAC bypass I documented in "Reading Your Way Around UAC" (parts 1, 2 and 3) has been fixed. This quick blog post will describe the relatively simple change MS made to the kernel to fix the UAC bypass and some musing on how it still might be possible to bypass.

As a quick recap, the UAC bypass I documented allowed any normal user on the same desktop to open a privileged UAC admin process and get a handle to the process' access token. The only requirement was there was an existing elevated process running on the desktop, but that's a very common behavior. That in itself didn't allow you to do much directly. However by duplicating the token which, made it writable, it was possible to selectively downgrade the token so that it could be impersonated.

Prior to Windows 10 all you needed to do was downgrade the token's integrity level to Medium. This left the token still containing the Administrators group, but it passed the kernel's checks for impersonation. This allows you to directly modify administrator only resources. For Windows 10 an elevation check was introduced which prevented a process in a non-elevated session from impersonating an elevated token. This was indicated by a flag in the limited token's logon session structure. If the flag was set, but you were impersonating an elevated token it'd fail. This didn't stop you from impersonating the token as long as it was considered non-elevated then abusing WMI to spawn a process in that session or the Secondary Logon Service to get back administrator privileges.

Let's look now at how it was fixed. The changed code is in the SeTokenCanImpersonate method which determines whether a token is allowed to impersonated or not.

TOKEN* process_token = ...;

TOKEN* imp_token = ...;

#define LIMITED_LOGON_SESSION 0x4

if (SeTokenIsElevated(imp_token)) {

if (!SeTokenIsElevated(process_token) &&

(process_token->LogonSession->Flags & LIMITED_LOGON_SESSION)) {

return STATUS_PRIVILEGE_NOT_HELD;

}

}

if (process_token->LogonSession->Flags & LIMITED_LOGON_SESSION

&& !(imp_token->LogonSession->Flags & LIMITED_LOGON_SESSION)) {

SepLogUnmatchedSessionFlagImpersonationAttempt();

return STATUS_PRIVILEGE_NOT_HELD;

}

The first part of the code is the same as was introduced in Windows 10. If you try and impersonate an elevated token and your process is running in the limited logon session it'll be rejected. The new check introduced ensures that if you're in the limited logon session you're not trying to impersonate a token in a non-limited logon session. And there goes the UAC bypass, using any variation of the attack you need to impersonate the token to elevate your privileges.

The fix is pretty simple, although I can't help think there must be some edge case which this would trip up. The only case which comes to mind in tokens returned from the LogonUser APIs, however those are special cases earlier in the function so I could imagine this would only be a problem when there might be a more significant security bug.

It's worth bearing in mind that due to the way Microsoft fixes bugs in UAC this will not be ported to versions prior to RS5. So if you're on a Windows Vista through Windows 10 RS4 machine you can still abuse this to bypass UAC, in most cases silently. And there's hardly a lack of other UAC bypasses, you just have to look at UACME. Though I'll admit none of the bypasses are as interesting to me as a fundamental design flaw in the whole technology. The only thing I can say is Microsoft seems committed to fixing these bugs eventually, even if they seem to introduce more UAC bypasses in each release.

Can this fix be bypassed? It's predicated on the user not having control over a process running outside of the limited logon session. A potential counter example would be processes spawned from an elevated process where the token is intentionally restricted, such as in sandboxed applications such as Adobe Reader or Chrome. However in order for that to be exploitable you'd need to convince the user to elevate those applications which doesn't make for a general technique. There's of course potential impersonation bugs, such as my Constrained Impersonation attack which could be used to bypass Over-The-Shoulder elevation but also could be used to impersonate SYSTEM tokens. Bugs like that tend to be something Microsoft want to fix (the Constrained Impersonation one was fixed as CVE-2018-0821) so again not a general technique.

I did have a quick think about other ways of bypassing this, then I realized I don't actually care ;-)

Tuesday 9 October 2018

Sunday 9 September 2018

Finding Interactive User COM Objects using PowerShell

Easily one of the most interesting blogs on Windows behaviour is Raymond Chen's The Old New Thing. I noticed he'd recently posted about using "Interactive User" (IU) COM objects to go from an elevated application (in the UAC sense) to the current user for the desktop. What interested me is that registering arbitrary COM objects as IU can have security consequences, and of course this blog entry didn't mention anything about that.

The two potential security issues can be summarised as:

The two potential security issues can be summarised as:

- An IU COM object can be a sandbox escape if it has non-default security (for example Project Zero Issue 1079) as you can start a COM server outside the sandbox and call methods on the object.

- An IU COM object can be a cross-session elevation of privilege if it has non-default security ( for example Project Zero Issue 1021) as you can start a COM server in a different console session and call methods on the object.

I've blogged about this before when I discuss how I exploited a reference cycle bug in NtCreateLowBoxToken (see Project Zero Issue 483) and discussed how to use my OleView.NET tool find classes to check. Why do I need another blog post about it? I recently uploaded version 1.5 of my OleView.NET tool which comes with a fairly comprehensive PowerShell module and this seemed like a good opportunity on doing a quick tutorial on using the module to find targets for analysis to see if you can find a new sandbox escape or cross session exploit.

Note I'm not discussing how you go about reverse engineering the COM implementation for anything we find. I also won't be dropping any unknown bugs, but just giving you the information needed to find interesting COM servers.

Getting Started with PowerShell Module

First things first, you'll need to grab the release of v1.5 from the THIS LINK (edit: you can now also get the module from the PowerShell Gallery). Unpack it to a directory on your system then open PowerShell and navigate to the unpacked directory. Make sure you've allowed arbitrary scripts to run in PS, then run the following command to load the module.

PS C:\> Import-Module .\OleViewDotNet.psd1

As long as you see no errors the PS module will now be loaded. Next we need to capture a database of all COM registration information on the current machine. Normally when you open the GUI of OleView.NET the database will be loaded automatically, but not in the module. Instead you'll need load it manually using the following command:

PS C:\> Get-ComDatabase -SetCurrent

The Get-ComDatabase cmdlet parses the system configuration for all COM information my tool knowns about. This can take some time (maybe up to a minute, more if you have Process Monitor running), so it'll show a progress dialog. By specifying the -SetCurrent parameter we will store the database as the current global database, for the current session. Many of the commands in the module take a -Database parameter where you can specify the database you want to extract information from. Ensuring you pass the correct value gets tedious after a while so by setting the current database you never need to specify the database explicitly (unless you want to use a different one).

Now it's going to suck if every time you want to look at some COM information you need to run the lengthy Get-ComDatabase command. Trust me, I've stared at the progress bar too long. That's why I implemented a simple save and reload feature. Running the following command will write the current database out to the file com.db:

PS C:\> Set-ComDatabase .\com.db

You can then reload using the following command:

PS C:\> Get-ComDatabase .\com.db -SetCurrent

You'll find this is significantly faster. Worth noting, if you open a 64 bit PS command line you'll capture a database of the 64 bit view of COM, where as in 32 bit PS you'll get a 32 bit view.

Finding Interactive User COM Servers

With the database loaded we can now query the database for COM registration information. You can get a handle to the underlying database object as the variable $comdb using the following command:

PS C:\> $comdb = Get-CurrentComDatabase

However, I wouldn't recommend using the COM database directly as it's not really designed for ease of use. Instead I provide various cmdlets to extract information from the database which I've summarised in the following table:

Command

|

Description

|

Get-ComClass

|

Get list of registered COM classes

|

Get-ComInterface

|

Get list of registered COM interfaces

|

Get-ComAppId

|

Get list of registered COM AppIDs

|

Get-ComCategory

|

Get list of registered COM categories

|

Get-ComRuntimeClass

|

Get list of Windows Runtime classes

|

Get-ComRuntimeServer

|

Get list of Windows Runtime servers

|

Each command defaults to returning all registered objects from the database. They also take a range of parameters to filter the output to a collection or a single entry. I'd recommend passing the name of the command to Get-Help to see descriptions of the parameters and examples of use.

Why didn't I expose it as a relational database, say using SQL? The database is really an object collection and one thing PS is good at is interacting with objects. You can use the Where-Object command to filter objects, or Select-Object to extract certain properties and so on. Therefore it's probably a lot more work to build on a native query syntax that just let you write PS scripts to filter, sort and group. To make life easier I have spent some time trying to link objects together, so for example each COM class object has an AppIdEntry property which links to the object for the AppID (if registered). In turn the AppID entry has a ClassEntries property which will then tell you all classes registered with that AppID.

Okay, let's get a list of classes that are registered with RunAs set to "Interactive User". The class object returned from Get-ComClass has a RunAs property which is set to the name of the user account that the COM server runs as. You also need to only look for COM servers which run out of process, we can do this by filtering for only LocalServer32 classes.

Run the following command to do the filtering:

PS C:\> $runas = Get-GetComClass -ServerType LocalServer32 | ? RunAs -eq "Interactive User"

You should now find the $runas variable contains a list of classes which will run as IU. If you don't believe me you can double check by just selecting out the RunAs property (the default table view won't show it) using the following:

PS C:\> $runas | Select Name, RunAs

Name RunAs

---- -----

BrowserBroker Class Interactive User

User Notification Interactive User

...

On my machine I have around 200 classes installed that will run as IU. But that's not the end of the story, only a subset of these classes will actually be accessible from a sandbox such as Edge or cross-session. We need a way of filtering them down further. To filter we'll need to look at the associated security of the class registration, specifically the Launch and Access permissions. In order to launch the new object and get an instance of the class we'll need to be granted Launch Permission, then in order to access the object we get back we'll need to be granted Access Permissions. The class object exposes this as the LaunchPermission and AccessPermission properties respectively. However, these just contain a Security Descriptor Definition Language (SDDL) string representation of the security descriptor, which isn't easy to understand at the best of times. Fortunately I've made it easier, you can use the Select-ComAccess cmdlet to filter on classes which can be accessed from certain scenarios.

Let's first look at what objects we could access from the Edge content sandbox. First we need the access token of a sandboxed Edge process. The easiest way to get that is just to start Edge and open the token from one of the MicrosoftEdgeCP processes. Start Edge, then run the following to dump a list of the content processes.

PS C:\> Get-Process MicrosoftEdgeCP | Select Id, ProcessName

Id ProcessName

-- -----------

8872 MicrosoftEdgeCP

9156 MicrosoftEdgeCP

10040 MicrosoftEdgeCP

14856 MicrosoftEdgeCP

Just pick one of the PIDs, for this purpose it doesn't matter too much as all Edge CP's are more or less equivalent. Then pass the PID to the -ProcessId parameter for Select-ComAccess and pipe in the $runas variable we got from before.

PS C:\> $runas | Select-ComAccess -ProcessId 8872 | Select Name

Name

----

PerAppRuntimeBroker

...

On my system, that reduces the count of classes from 200 to 9 classes, which is a pretty significant reduction. If I rerun this command with a normal UWP sandboxed process (such as the calculator) that rises to 45 classes. Still fewer than 200 but a significantly larger attack surface. The reason for the reduction is Edge content processes use Low Privilege AppContainer (LPAC) which heavily cuts down inadvertent attack surface.

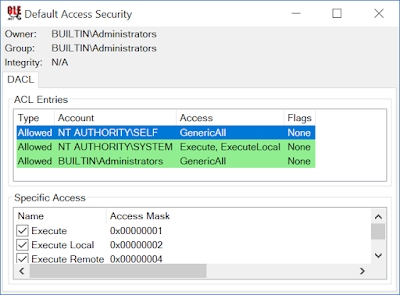

What about cross-session? The distinction here is you'll be running as one unsandboxed user account and would like to attack the another user account. This is quite important for the security of COM objects, the default access security descriptor uses the special SELF SID which is replaced by the user account of the process hosting the COM server. Of course if the server is running as a different user in a different session the defaults won't grant access. You can see the default security descriptor using the following command:

Show-ComSecurityDescriptor -Default -ShowAccess

This command results in a GUI being displayed with the default access security descriptor. You see in this screenshot that the first entry grants access to the SELF SID.

To test for accessible COM classes we just need to tell the access checking code to replace the SELF SID with another SID we're not granted access to. You can do this by passing a SID to the -Principal parameter. The SID can be anything as long as it's not our user account or one of the groups we have in our access token. Try running the following command:

PS C:\> $runas | Select-ComAccess -Principal S-1-2-3-4 | Select Name

Name

----

BrowserBroker Class

...

On my system that leaves around 54 classes, still a reduction from 200 but better than nothing and still gives plenty of attack surface.

Inspecting COM Objects

I've only shown you how to find potential targets to look at for sandbox escape or cross-session attacks. But the class still needs some sort of way of elevating privileges, such as a method on an interface which would execute an arbitrary executable or similar. Let's quickly look at some of the functions in the PS module which can help you to find this functionality. We'll use the example of the HxHelpPane class I abused previously (and is now fixed as a cross-session attack in Project Zero Issue 1224, probably).

The first thing is just to get a reference to the class object for the HxHelpPane server class. We can get the class using the following command:

PS C:\> $cls = Get-ComClass -Name "AP Client HxHelpPaneServer Class"

The $cls variable should now be a reference to the class object. First thing to do is find out what interfaces the class supports. In order to access a COM object OOP you need a registered COM proxy. We can use the list of registered proxy interfaces to find what the object responds to. Again I have command to do just that, Get-ComClassInterface. Run the following command to get back a list of interface objects:

PS C:\> Get-ComClassInterface $cls | Select Name, Iid

Name Iid

---- ---

IMarshal 00000003-0000-0000-c000-000000000046

IUnknown 00000000-0000-0000-c000-000000000046

IMultiQI 00000020-0000-0000-c000-000000000046

IClientSecurity 0000013d-0000-0000-c000-000000000046

IHxHelpPaneServer 8cec592c-07a1-11d9-b15e-000d56bfe6ee

Sometimes there's interesting interfaces on the factory object as well, you can get the list of interfaces for that by specifying the -Factory parameter to Get-ComClassInterface. Of the interfaces shown only IHxHelpServer is unique to this class, the rest are standard COM interfaces. That's not to say they won't have interesting behavior but it wouldn't be the first place I'd look for interesting methods.

The implementation of these interfaces are likely to be in the COM server binary, where is that? We can just inspect the DefaultServer property on the class object.

PS C:\> $cls.DefaultServer

C:\Windows\helppane.exe

We can now just break out IDA and go to town? Not so fast, it'd be useful to know exactly what we're dealing with before then. At this point I'd recommend at least using my tools NDR parsing code to extract how the interface is structured. You can do this by pass an interface object from Get-ComClassInterface or just normal Get-ComInterface into the Get-ComProxy command. Unfortunately if you do this you'll find a problem:

PS C:\> Get-ComInterface -Name IHxHelpPaneServer | Get-ComProxy

Exception: "Error while parsing NDR structures"

At OleViewDotNet.psm1:1587 char:17

+ [OleViewDotNet.COMProxyInterfaceInstance]::GetFromIID($In

+ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

+ CategoryInfo : NotSpecified: (:) []

+ FullyQualifiedErrorId : NdrParserException

This could be bug in my code, but there's a more likely reason. The proxy could be an auto-created proxy from a type library. We can check that using the following:

PS C:\> Get-ComInterface -Name IHxHelpPaneServer

Name IID HasProxy HasTypeLib

---- --- -------- ----------

IHxHelpPaneServer 8cec592c-07a1... True True

We can see if the output that the interface has a registered type library, for an interface this likely means its proxy is auto-generated. Where's the type library? Again we can use another database command, Get-ComTypeLib and pass it the IID of the interface:

PS C:\> Get-ComTypeLib -Iid 8cec592c-07a1-11d9-b15e-000d56bfe6ee

TypelibId : 8cec5860-07a1-11d9-b15e-000d56bfe6ee

Version : 1.0

Name : AP Client 1.0 Type Library

Win32Path : C:\Windows\HelpPane.exe

Win64Path : C:\Windows\HelpPane.exe

Locale : 0

NativePath : C:\Windows\HelpPane.exe

Now you can use your favourite tool to decompile the type library to get back your interface information. You can also use the following command if you capture the type library information to the variable $tlb:

PS C:\> Get-ComTypeLibAssembly $tlb | Format-ComTypeLib

...

[Guid("8cec592c-07a1-11d9-b15e-000d56bfe6ee")]

interface IHxHelpPaneServer

{

/* Methods */

void DisplayTask(string bstrUrl);

void DisplayContents(string bstrUrl);

void DisplaySearchResults(string bstrSearchQuery);

void Execute(string pcUrl);

}

You now know the likely names of functions which should aid you in looking them up in IDA or similar. That's the end of this quick tutorial, there's plenty more to discover in the PS module you'll just have to poke around at it and see. Happy hunting.

Sunday 22 July 2018

UWP Localhost Network Isolation and Edge

This blog post describes an interesting

“feature” added to Windows to support Edge accessing the loopback network

interface. For reference this was on Windows 10 1803 running Edge 42.17134.1.0

as well as verifying on Windows 10 RS5 17713 running 43.17713.1000.0.

I like the concept of the App Container (AC)

sandbox Microsoft introduced in Windows 8. It moved sandboxing on Windows from

restricted tokens which were hard to reason about and required massive cludges

to get working to a reasonably consistent capability based model where you are

heavily limited in what you can do unless you’ve been granted an explicit

capability when your application is started. On Windows 8 this was limited to a

small set of known capabilities. On Windows 10 this has been expanded massively

by effectively allowing an application to define its own capabilities and

enforce them though the normal Windows access control mechanisms.

I’ve been looking at AC more and it's ability

to do network isolation, where access to the network requires being granted

capabilities such as “internetClient”, seems very useful. It’s a little known

fact that even in the most heavily locked down, restricted token sandbox it’s

possible to open network sockets by accessing the raw AFD driver. AC solves this

issue quite well, it doesn’t block access to the AFD driver, instead the

Firewall checks for the capabilities and blocks connecting or accepting

sockets.

One issue does come up with building a generic

sandboxing mechanism this AC network isolation primitive is regardless of what

capabilities you grant it’s not possible for an AC application to access

localhost. For example you might want your sandboxed application to access a

web server on localhost for testing, or use a localhost proxy to MITM the traffic.

Neither of these scenarios can be made to work in an AC sandbox with

capabilities alone.

The likely rationale for blocking localhost is

allowing sandboxed content access can also be a big security risk. Windows runs

quite a few services accessible locally which could be abused, such as the SMB

server. Rather than adding a capability to grant access to localhost, there's

an explicit list of packages exempt from the localhost restriction stored by

the firewall service. You can access or modify this list using the Firewall APIs such as the NetworkIsolationSetAppContainerConfig

function or using the CheckNetIsolation

tool installed with Windows. This behavior seems to be rationalized as

accessing loopback is a developer feature, not something which real

applications should rely on. Curious, I wondered whether I had AC’s already in

the exemption list. You can list all available exemptions by running “CheckNetIsolation

LoopbackExempt -s” on the command line.

On my Windows 10 machine we can see two

exemptions already installed, which is odd for a developer feature which no

applications should be using. The first entry shows “AppContainer NOT FOUND”

which indicates that the registered SID doesn’t correspond to a registered AC.

The second entry shows a very unhelpful name of “001” which at least means it’s

an application on the current system. What’s going on? We can use my NtObjectManager PS module and it's 'Get-NtSid' cmdlet on the

second SID to see if that can resolve a better name.

Ahha, “001” is actually a child AC of the Edge

package, we could have guessed this by looking at the length of the SID, a

normal AC SID had 8 sub authorities, whereas a child has 12, with the extra 4

being added to the end of the base AC SID. Looking back at the unregistered SID

we can see it’s also an Edge AC SID just with a child which isn’t actually

registered. The “001” AC seems to be the one used to host Internet content, at

least based on the browser security whitepaper from X41Sec (see page

54).

This is not exactly surprising. It seems when

Edge was first released it wasn’t possible to access localhost resources at all

(as demonstrated by an IBM help article which instructs

the user to use CheckNetIsolation to

add an exemption). However, at some point in development MS added an about:flags option to enable accessing

localhost, and seems it’s now the default configuration, even though as you can

see in the following screenshot it says enabling can put your device at risk.

What’s interesting though is if you disable

the flags option and restart Edge then the exemption entry is deleted, and

re-enabling it restores the entry again. Why is that a surprise? Well based on

previous knowledge of this exemption feature, such as this blog post by Eric Lawrence you

need admin privileges to change the

exemption list. Perhaps MS have changed that behavior now? Let’s try and add an

exemption using the CheckNetIsolation

tool as a normal user, passing “-a -p=SID” parameters.

I guess they haven’t as adding a new exemption

using the CheckNetIsolation tool

gives us access denied. Now I’m really interested. With Edge being a built-in

application of course there’s plenty of ways that MS could have fudged the

“security” checks to allow Edge to add itself to the list, but where is it?

The simplest location to add the fudge would

be in the RPC service which implements the NetworkIsolationSetAppContainerConfig.

(How do I know there's an RPC service? I just disassembled the API). I took a

guess and assumed the implementation would be hosted in the “Windows Defender

Firewall” service, which is implemented in the MPSSVC DLL. The following is a

simplified version of the RPC server method for the API.

HRESULT

RPC_NetworkIsolationSetAppContainerConfig(handle_t handle,

DWORD dwNumPublicAppCs,

PSID_AND_ATTRIBUTES appContainerSids) {

if (!FwRpcAPIsIsPackageAccessGranted(handle)) {

HRESULT hr;

BOOL developer_mode = FALSE:

IsDeveloperModeEnabled(&developer_mode);

if (developer_mode) {

hr = FwRpcAPIsSecModeAccessCheckForClient(1, handle);

if (FAILED(hr)) {

return hr;

}

}

else

{

hr = FwRpcAPIsSecModeAccessCheckForClient(2, handle);

if (FAILED(hr)) {

return hr;

}

}

}

return FwMoneisAppContainerSetConfig(dwNumPublicAppCs,

appContainerSids);

}

DWORD dwNumPublicAppCs,

PSID_AND_ATTRIBUTES appContainerSids) {

if (!FwRpcAPIsIsPackageAccessGranted(handle)) {

HRESULT hr;

BOOL developer_mode = FALSE:

IsDeveloperModeEnabled(&developer_mode);

if (developer_mode) {

hr = FwRpcAPIsSecModeAccessCheckForClient(1, handle);

if (FAILED(hr)) {

return hr;

}

}

else

{

hr = FwRpcAPIsSecModeAccessCheckForClient(2, handle);

if (FAILED(hr)) {

return hr;

}

}

}

return FwMoneisAppContainerSetConfig(dwNumPublicAppCs,

appContainerSids);

}

What’s immediately obvious is there's a method

call, FwRpcAPIsIsPackageAccessGranted,

which has “Package” in the name which might indicate it’s inspecting some AC

package information. If this call succeeds then the following security checks

are bypassed and the real function FwMoneisAppContainerSetConfig

is called. It's also worth noting that the security checks differ depending on

whether you're in developer mode or not. It turns out that if you have

developer mode enabled then you can also bypass the admin check, which is

confirmation the exemption list was designed primarily as a developer feature.

Anyway let's take a look at FwRpcAPIsIsPackageAccessGranted to see

what it’s checking.

const WCHAR* allowedPackageFamilies[] = {

L"Microsoft.MicrosoftEdge_8wekyb3d8bbwe",

L"Microsoft.MicrosoftEdgeBeta_8wekyb3d8bbwe",

L"Microsoft.zMicrosoftEdge_8wekyb3d8bbwe"

};

HRESULT FwRpcAPIsIsPackageAccessGranted(handle_t handle) {

HANDLE token;

FwRpcAPIsGetAccessTokenFromClientBinding(handle, &token);

WCHAR* package_id;

RtlQueryPackageIdentity(token, &package_id);

WCHAR family_name[0x100];

PackageFamilyNameFromFullName(package_id, family_name)

for (int i = 0;

i < _countof(allowedPackageFamilies);

++i) {

if (wcsicmp(family_name,

allowedPackageFamilies[i]) == 0) {

return S_OK;

}

}

return E_FAIL;

}

L"Microsoft.MicrosoftEdge_8wekyb3d8bbwe",

L"Microsoft.MicrosoftEdgeBeta_8wekyb3d8bbwe",

L"Microsoft.zMicrosoftEdge_8wekyb3d8bbwe"

};

HRESULT FwRpcAPIsIsPackageAccessGranted(handle_t handle) {

HANDLE token;

FwRpcAPIsGetAccessTokenFromClientBinding(handle, &token);

WCHAR* package_id;

RtlQueryPackageIdentity(token, &package_id);

WCHAR family_name[0x100];

PackageFamilyNameFromFullName(package_id, family_name)

for (int i = 0;

i < _countof(allowedPackageFamilies);

++i) {

if (wcsicmp(family_name,

allowedPackageFamilies[i]) == 0) {

return S_OK;

}

}

return E_FAIL;

}

The FwRpcAPIsIsPackageAccessGranted

function gets the caller’s token, queries for the package family name and

then checks it against a hard coded list. If the caller is in the Edge package

(or some beta versions) the function returns success which results in the admin

check being bypassed. The conclusion we can take is this is how Edge is adding

itself to the exemption list, although we also want to check what access is

required to the RPC server. For an ALPC server there’s two security checks,

connecting to the ALPC port and an optional security callback. We could reverse

engineer it from service binary but it is easier just to dump it from the ALPC

server port, again we can use my NtObjectManager

module.

As the RPC service doesn’t specify a name for

the service then the RPC libraries generate a random name of the form

“LRPC-XXXXX”. You would usually use EPMAPPER to find the real name but I just

used a debugger on CheckNetIsolation

to break on NtAlpcConnectPort and

dumped the connection name. Then we just find the handle to that ALPC port in

the service process and dump the security descriptor. The list contains Everyone and all the various network

related capabilities, so any AC process with network access can talk to these

APIs including Edge LPAC. Therefore all Edge processes can access this

capability and add arbitrary packages. The implementation inside Edge is in the

function emodel!SetACLoopbackExemptions.

With this knowledge we can now put together

some code which will exploit this “feature” to add arbitrary exemptions. You can find the

PowerShell script on my Github gist.

Wrap Up

If I was willing to speculate (and I am) I’d

say the reason that MS added localhost access this way is it didn’t require

modifying kernel drivers, it could all be done with changes to user mode

components. Of course the cynic in me thinks this could actually be just there

to make Edge more equal than others, assuming MS ever allowed another web

browser in the App Store. Even a wrapper around the Edge renderer would not be

allowed to add the localhost exemption. It’d be nice to see MS add a capability

to do this in the future, but considering current RS5 builds use this same

approach I’m not hopeful.

Is this a security issue? Well that depends.

On the one hand you could argue the default configuration which allows Internet

facing content to then access localhost is dangerous in itself, they point that

out explicitly in the about:flags

entry. Then again all browsers have this behavior so I’m not sure it’s really

an issue.

The implementation is pretty sloppy and I’m

shocked (well not that shocked) that it passed a security review. To list some

of the issues with it:

●

The package family check isn’t

very restrictive, combined with the weak permissions of the RPC service it

allows any Edge process to add an arbitrary exemption.

●

The exemption isn’t linked to the

calling process, so any SID can be added as an exemption.

While it seems the default is only to allow

the Internet facing ACs access to localhost because of these weaknesses if you

compromised a Flash process (which is child AC “006”) then it could

add itself an exemption and try and attack services listening on localhost. It would make more sense if only the main MicrosoftEdge

process could add the exemptions, not any content process. But what would make

the most sense would be to support this functionality through a capability so

that everyone could take advantage of it rather than implementing it as a

backdoor.

Monday 25 June 2018

Disabling AMSI in JScript with One Simple Trick

This blog contains a very quick and dirty way to disable AMSI in the context of Windows Scripting Host which doesn't require admin privileges or modifying registry keys/system state which an AV such as Defender should pick up on. It's for information purposes only, I've tested this on an up-to-date Windows 10 1803 machine.

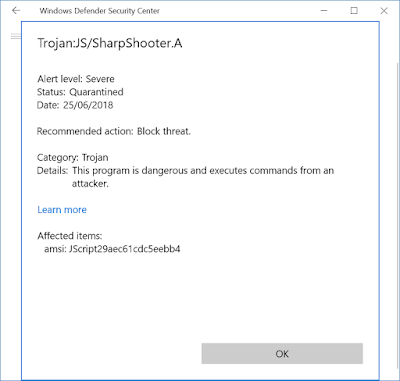

It's come to my attention that a default script file from DotNetToJScript no longer works because Windows Defender blocks it, thanks a lot everyone who contributed to getting my tools flagged as malware.

If you look carefully in the screenshot you'll see it shows that the "Affected items:" is prefixed with amsi:. This is an indication that the detection wasn't based on the file but due to behavior through the Antimalware Scan Interface. Certainly the script could be reworked to get around this issue (it seems to work for example in scriptlets oddly enough) but I'll probably never need to bother as I never wrote it for the use cases "Sharpshooter" uses it for. Still I had an idea for a way of bypassing AMSI which I thought I'd test out.

I was in part inspired to dig this technique out again after seeing MDSec's recent work on newer bypasses for AMSI in PowerShell as well as a BlackHat Asia talk from Tal Liberman. However I've not seen this technique described anywhere else, but I'm sure someone can correct me if I'm wrong.

These are somewhat interconnected. For example Tal Liberman mentions in his presentation (slide 56) that you could copy an AMSI using application to another directory and it will try and load AMSI.DLL from that directory. As this AMSI can be some unrelated DLL which doesn't export AmsiInitialize then the load will succeed but the rest will fail. Unfortunately this trick won't work here as the flag LOAD_LIBRARY_SEARCH_SYSTEM32 is being passed which means LoadLibraryEx will always try and load from SYSTEM32 first. Getting AmsiInitialize to fail will be a pain, and we can't trivially prevent this code load AMSI.DLL from SYSTEM32, so what do we do? We preload an alternative AMSI.DLL of course.

This results in a process called AMSI.DLL running. When JScript or VBScript tries to load AMSI.DLL it now gets back a reference to main executable and AMSI no longer works. From what I can tell this short script doesn't get detected by AMSI itself, so it's safe to run to bootstrap the "real" code you want to run.

To summarise the attack:

AFAIK this doesn't work with PowerShell because it seems to break something important inside the code which renders PS inoperable. Whether this is by design or not I've no idea. Anyway, I know this is a silly way of bypassing AMSI but it just shows that this sort of self-checking feature rarely works out very well when malware could very easily modify the platform which is doing the detection.

It's come to my attention that a default script file from DotNetToJScript no longer works because Windows Defender blocks it, thanks a lot everyone who contributed to getting my tools flagged as malware.

I was in part inspired to dig this technique out again after seeing MDSec's recent work on newer bypasses for AMSI in PowerShell as well as a BlackHat Asia talk from Tal Liberman. However I've not seen this technique described anywhere else, but I'm sure someone can correct me if I'm wrong.

How AMSI Is Loaded in Windows Scripting Host

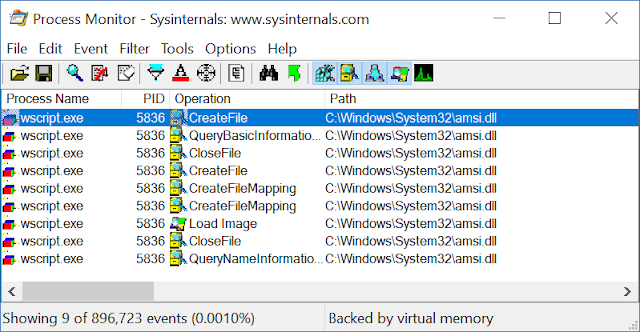

AMSI is implemented as an COM server which is used to communicate to the installed security product via an internal channel. A previous attack against AMSI was actually to hijack this COM registration as documented by Matt Nelson. The scripting host is not supposed to call the COM object directly, instead it calls methods via exported functions in AMSI.DLL, we can watch being loaded by setting an appropriate filter in Process Monitor.

We can use the stack trace feature of Process Monitor to find the code responsible for loading AMSI.DLL. It's actually part of the scripting engine, such as JScript or VBScript rather than a core part of WSH. The basics of the code are below.

HRESULT COleScript::Initialize() { hAmsiModule = LoadLibraryExW(L"amsi.dll", nullptr, LOAD_LIBRARY_SEARCH_SYSTEM32); if (hAmsiModule) { ① // Get initialization functions. FARPROC pAmsiInit = GetProcAddress(hAmsiModule, "AmsiInitialize"); pAmsiScanString = GetProcAddress(hAmsiModule, "AmsiScanString"); if (pAmsiInit){ if (pAmsiScanString && FAILED(pAmsiInit(&hAmsiContext))) ② hAmsiContext = nullptr; } } bInit = TRUE; ③ return bInit; }

Based on this code we can see it loading the AMSI DLL ① then calling AmsiInitialize ② to get a context handle. The interesting thing about this code is regardless of whether AMSI initializes or not it will always return success ③. This leads to three ways of causing this code to fail and therefore never initialize AMSI, block loading AMSI.DLL, make AMSI.DLL not contain methods such as AmsiInitialize, or cause AmsiInitialize to fail.HRESULT COleScript::Initialize() { hAmsiModule = LoadLibraryExW(L"amsi.dll", nullptr, LOAD_LIBRARY_SEARCH_SYSTEM32); if (hAmsiModule) { ① // Get initialization functions. FARPROC pAmsiInit = GetProcAddress(hAmsiModule, "AmsiInitialize"); pAmsiScanString = GetProcAddress(hAmsiModule, "AmsiScanString"); if (pAmsiInit){ if (pAmsiScanString && FAILED(pAmsiInit(&hAmsiContext))) ② hAmsiContext = nullptr; } } bInit = TRUE; ③ return bInit; }

These are somewhat interconnected. For example Tal Liberman mentions in his presentation (slide 56) that you could copy an AMSI using application to another directory and it will try and load AMSI.DLL from that directory. As this AMSI can be some unrelated DLL which doesn't export AmsiInitialize then the load will succeed but the rest will fail. Unfortunately this trick won't work here as the flag LOAD_LIBRARY_SEARCH_SYSTEM32 is being passed which means LoadLibraryEx will always try and load from SYSTEM32 first. Getting AmsiInitialize to fail will be a pain, and we can't trivially prevent this code load AMSI.DLL from SYSTEM32, so what do we do? We preload an alternative AMSI.DLL of course.

Hijacking AMSI.DLL

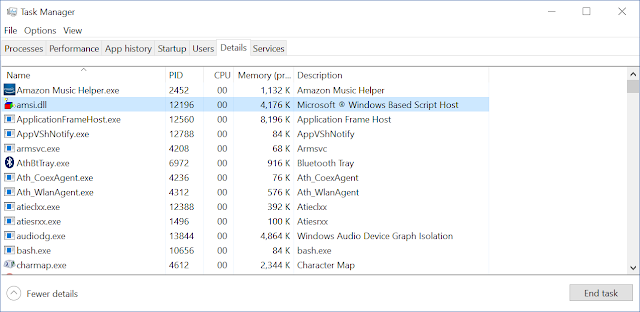

How do we go about loading an alternative AMSI.DLL with the least amount of effort possible? Something which perhaps not everyone realizes is that LoadLibrary will try and find an existing loaded DLL with the requested name so that it doesn't load the same DLL twice. This works not just for the name of the DLL but also the main executable. Therefore if we can convince the library loader that our main executable is actually called AMSI.DLL then it'll return that instead. Unable to find AmsiInitialize exported this should result in AMSI failing to initialize but continuing to execute a script without inspecting it.

How can we change the name of our main executable to AMSI.DLL without modifying process memory? Simple, we copy WSCRIPT.EXE to another directory but call it AMSI.DLL then run it. Wait, what? How can we run AMSI.DLL, doesn't it need to SOMETHING.EXE? On Windows there's two main ways of executing a process, ShellExecute or CreateProcess. When calling ShellExecute the API looks up the handler for the extension, such as .EXE or .DLL and performs particular actions based on the result. Generally .EXE will redirect to just calling CreateProcess, where as for .DLL it'll try and load it in a registered viewer, on a default system there probably isn't one. However, CreateProcess doesn't care what extension the file has as long as it's an Executable File based on its PE header. [Aside, you can actually execute a DLL using the native APIs, but we don't have access to that from WSH]. Therefore, as long as we can call CreateProcess on AMSI.DLL which is actually a copy of WSCRIPT.EXE it will execute. To do this we can just use WScript.Shell's Exec method which just calls CreateProcess directly.

var obj = new ActiveXObject("WScript.Shell");

obj.Exec("amsi.dll dotnettojscript.js");

This results in a process called AMSI.DLL running. When JScript or VBScript tries to load AMSI.DLL it now gets back a reference to main executable and AMSI no longer works. From what I can tell this short script doesn't get detected by AMSI itself, so it's safe to run to bootstrap the "real" code you want to run.

To summarise the attack:

- Start a stub script which copies WSCRIPT.EXE to a known location but with the name AMSI.DLL. This is still the same catalog signed executable just in a different location so would likely bypass detection based purely on signatures.

- In the stub script execute the newly created AMSI.DLL with the "real" script.

- Err, that's about it.

AFAIK this doesn't work with PowerShell because it seems to break something important inside the code which renders PS inoperable. Whether this is by design or not I've no idea. Anyway, I know this is a silly way of bypassing AMSI but it just shows that this sort of self-checking feature rarely works out very well when malware could very easily modify the platform which is doing the detection.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)