What rising inflation means for you: HUGO DUNCAN on why it dashes hopes of a Christmas Bank of England rate cut

There will be no early Christmas present from the Bank of England.

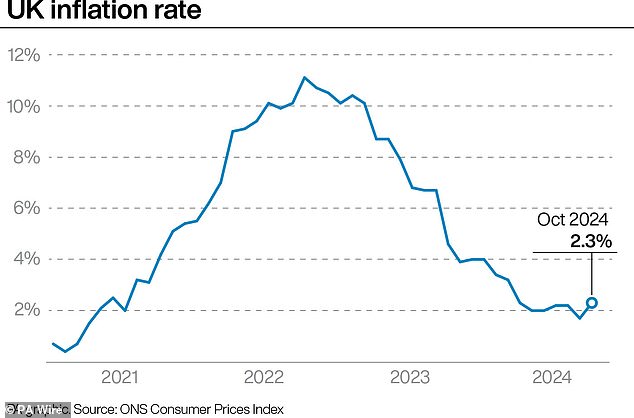

The jump in inflation announced today – from 1.7 per cent in September to 2.3 per cent in October – has dashed any lingering hopes of another interest rate cut this year.

The cost of living has once again been driven higher by the rise in household energy bills - the price cap went up from £1,568 to £1,717 per year at the start of last month.

Every household the country will be feeling the impact of more expensive heating right now as an Arctic blast sweeps across Britain.

A further rise in the price cap is expected in January - adding yet more pressure to household finances and inflation.

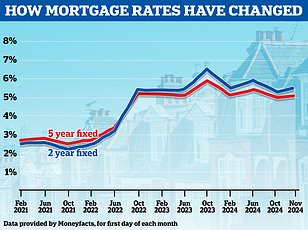

Inflation has a direct bearing on the cost of borrowing – and in particular the cost of mortgages facing millions of homeowners and those seeking to get on the housing ladder.

Inflation spiked to 2.3 per cent in October as fears grow over the impact of the Budget and global trade tensions

The jump in inflation announced today, from 1.7 per cent in September to 2.3 per cent in October, has dashed any hopes of another interest rate cut by the Bank of England (file image)

This is because the Bank of England typically raises interest rates to bring inflation under control and cuts rates when inflation is no longer a threat.

And today's news does not make pretty reading for those hoping for a round of rapid-fire rate cuts.

The jump in inflation from 1.7 per cent to 2.3 per cent was the biggest single month increase since October 2022 - though inflation was a punishing 11.1 per cent back then.

And the 2.3 per cent rise in prices on a year earlier was greater than feared.

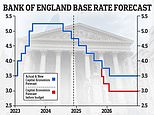

That means the Bank of England is less likely to cut interest rates in the coming months.

Indeed, the next move may not come before the spring. Just a few weeks ago it was hoped there would be a succession of cuts in the coming months.

The rates set by the Bank feed through to how much lenders charge borrowers for mortgages.

Mortgage rates soared as the Bank raised interest rates from an all-time low of 0.1 per cent in December 2021 to as high as 5.25 per cent in August 2023 to bring inflation down from its peak above 11 per cent.

There rates stayed until August this year when the Bank cut to 5 per cent. It cut them for a second time this month to 4.75 per cent.

The reductions have so far been far slower than many would have wanted – meaning mortgage rates remain high.

But it's not just the impact of higher energy bills on todays inflation rate that is giving the Bank cause for concern.

The Chancellor's Budget is also seen as a threat to inflation - with the boost to the minimum wage and increase in national insurance contributions paid by employers likely to lead to higher prices while also costing jobs.

Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey only yesterday warned that measures introduced by Rachel Reeves mean further rate cuts must be 'gradual'.

In other words, the Chancellor's spending splurge - paid for by higher taxes and more borrowing - risks making mortgages more expensive than they may otherwise have been.

Another hit to the 'working people' she promised to help.

Global events also have a bearing on borrowing costs in the UK – from Donald Trump's election in the US to the impact on energy prices of war in Ukraine and the Middle East.

But while a rate cut for Christmas now seems improbable, the outlook for inflation means interest rates are likely to fall again next year.

The problem for many, however, is the cuts may not come as fast as they would like.