Freedom was first sighted in our Catskills town on April 13. He looked undernourished with ribs showing through his coat. But he was also skittish, and although the woman who found the dog managed to pick him up, he wriggled free before she could put a collar on him and then disappeared in the direction of Broad Street. The dog looked like a Shiba Inu, a small sturdy Japanese breed originally used for hunting. At least one person on the town’s Facebook page wondered if he was a fox. The error was understandable. Shiba Inus resemble stocky foxes with jaunty curled tails. The tail and their narrow eyes make it easy to see them as jokers, tricksters, clowns. They also have a rep as escape artists.

A Shiba Inu is not a mutt. A purebred puppy can go for $3,500. But no owner came forward to claim this one. The fugitive made more appearances around the village. Rumors circulated: There was an owner, but this person was keeping a low profile because they’d rescued the dog from a predecessor who had abused him. The dog had a name, maybe Kaluw. This might have made it easier to capture if you knew how to say Kaluw. Was it Dutch? “Shame on the owner who doesn’t care for this dog,” someone posted. The reply came: “Let’s not even refer to him as the owner any longer, he obviously doesn’t give a crap.”

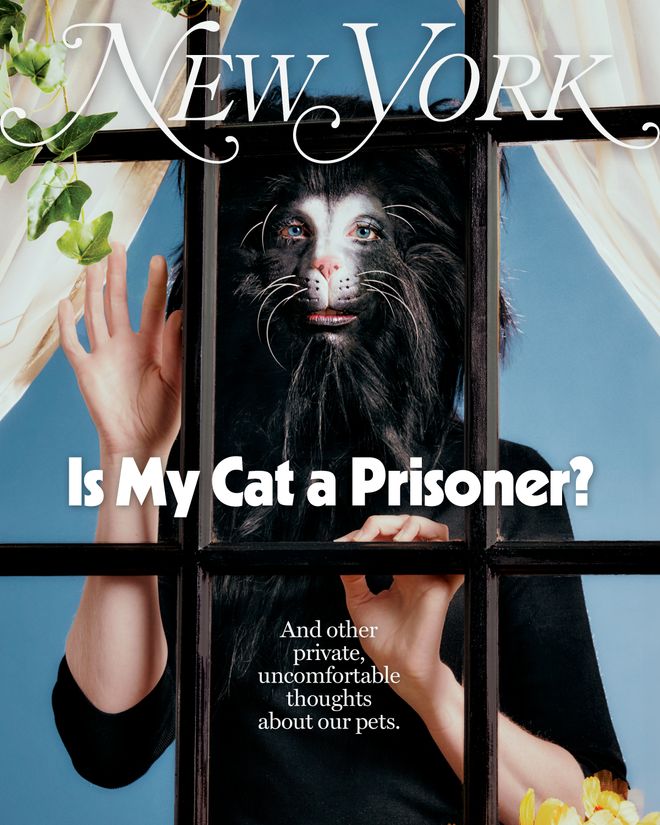

In This Issue

A month passed. The dog popped up everywhere. There were people who wanted to feed him, including one woman who announced she was staking out the playground “holding stinky hot dogs to the wind.” Jamie Hyer-Mitchell, the proprietor of Hyer Ground Rescue, warned that feeding the Shiba would make it harder to lure him into one of the traps that had been set up along what by now was understood to be his route. Was the Shiba Inu suffering? Was he, as some said, emaciated and limping? Others said he was eating handouts and trying to play with the dogs he came across. My wife said she saw him trotting. She thought he looked okay. We had decided he was neglected and abandoned, but what if he really was living his best life? Maybe he wanted to be free. “Free to go where he wants,” somebody posted. “No one telling him no!” And so people started calling him Freedom.

My sense is that this wasn’t so much a position as a vibe. People liked the idea of a dog slipping off the leash, dodging the dogcatcher (or, in our town, the DCO — the dog-control officer), outwitting and outrunning all pursuers. The writer Scott Spencer recalls watching a sheepdog demonstration at the annual sheep and wool festival in Rhinebeck when one of the dogs broke training and began chasing the sheep. Other dogs joined in. The sheep wheeled in panic, their eyes rolling, spittle flying from their mouths. “And the people watching went crazy!” Spencer says. “They were cheering! They loved seeing the norms being broken.” I think the Freedom Faction felt the same. Maybe the older members remembered the old Dylan song: “If dogs run free, then why not we?”

There’s a school of thought that pet ownership is inherently immoral since it entails treating an animal not as an autonomous living being but as a piece of property. The animal-rights activists Gary L. Francione and Anna E. Charlton argue that “if animals are property, they can have no inherent or intrinsic value. They have only extrinsic or external value. They are things that we value. They have no rights; we have rights, as property owners, to value them. And we might choose to value them at zero.” This might seem purely academic, but whoever owned the Shiba Inu appeared to have placed little value on him — not enough, at any rate, to have kept him from straying or to ask the community for help getting him back.

Speaking of norms, a dog’s norm “is to sit patiently while you fill its bowl and come when you call it,” Spencer tells me. “And though people may love seeing a dog run free, a dog running free doesn’t live long.” Dogs aren’t wild creatures. They’re creatures that came into being through domestication. They want what humans can give them: regular meals and a soft place to sleep. Dogs that lack those things are usually feral or homeless or abandoned, and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, whose The Hidden Life of Dogs may be the best and most loving dive into canine psychology, says that such dogs are “not living under conditions that are natural to them, any more than are wild animals in captivity, imprisoned in laboratories and zoos.” Without their partners in domestication, they’re under stress. Much of the Shiba Inu’s behavior suggested that he was, too. The ceaseless, restless scurrying, the approaches to other dogs that turned to flight when a human came too close, suggested a being torn between loneliness and fear. With each day he remained on the loose, the greater the risk that he’d be struck by a car or killed by a coyote or fisher cat.

Freedom was captured on May 15 by a team of rescuers, including Hyer-Mitchell. They found the dog in a fenced-in yard; all they had to do was close the gate to capture him. “And I say captured, not rescued, because it was too a capture — you can say whatever you want,” Hyer-Mitchell says. Back at the shelter, she assessed how Freedom felt about his freedom or lack thereof. “He was shaking like a leaf, and he was covered with ticks,” she says. “But he was the sweetest dog. There was absolutely no fighting, no fear-biting, no struggling.” She thought he was relieved: “You could tell he was exhausted.”

Freedom’s former owner was given a chance to make a case for reclaiming his property and either declined that chance or was turned down, but in any case he was ticketed for having a dog running at large and without a tag. The dog was rehomed with another family, which already had a Shiba Inu. I hope the two dogs have become friends. The runaway became a village meme. On the community Facebook, you can see a mural of his squinty little face grinning out at the village he mesmerized and confounded. He’s been given back his old name, which turns out to be not Freedom or Kaluw but Loki. Some of his fans still speak wistfully of his time on the run. “I know he’s better off where he is,” one tells me, “but his soul wanted to run among the village freely.”

Is My Cat a Prisoner? And other ethical questions about pets like …

➭ Are We Forcing Our Pets to Live Too Long?

➭ Am I a Terrible Pet Parent?

➭ Why Did I Stop Loving My Cat When I Had a Baby?

➭ What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets?

➭ I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

➭ Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior?

➭ Should I Give My Terrier ‘Experiences’?

➭ Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl?

➭ Are We Lying to Ourselves About Emotional-Support Animals?

➭ Does My Dog Hate Bushwick?

➭ How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug?