This story was featured in The Must Read, a newsletter in which our editors recommend one can’t-miss story every weekday. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Three stone deities stand watch over the entrance of the Asian Garden Mall, in Orange County’s Little Saigon. The mall is a cultural hub for Southern California’s enormous Vietnamese population. Old men sit nearby, smoking and talking heatedly over newspapers—actual newspapers—beneath a waving South Vietnamese flag. A steady stream of visitors approach to take photos in front of the façade.

Among them, more naturally than you might imagine possible, comes John Mulaney, pushing a stroller and pausing to rub the belly of a stone Buddha for good luck. Alongside are his mother-in-law, Dung Kim Schmid, and her husband, a mild-mannered retired optometrist named Sam. They are visiting Southern California from Oklahoma City on the occasion of the arrival of the stroller’s occupant: Mulaney and wife Olivia Munn’s second child, a daughter named Méi June.

They stop to regard the deity statues: Phuoc representing fortune; Loc, prosperity; and Tho, longevity. “Would you really want the longevity if you don’t have the prosperity and fortune?” Mulaney muses, though it wasn’t all that long ago that he was in danger of having exactly the opposite problem.

If this seems a strange place to find yourself at the start of a profile of John Mulaney, you might consider how John Mulaney feels. Once such a consummate urbanite that you half expected to see a pigeon on his head and his pockets stuffed with takeout menus, today he looks every inch a suburban dad, in his white lace-up Vans, olive jeans, long-sleeve shirt. Only days ago, he and his family, which also includes Malcolm, who is nearly three, moved into a new house overlooking the ocean. With Méi came a massive, new three-row SUV, though, frankly, it seems like a lot of car for John Mulaney, much less a tiny baby.

Sometimes, he says, he imagines himself a character in the TV show Quantum Leap who somehow ended up in the body of a dad at Sky Zone, the chain of indoor trampoline parks. “I would come to in all these foam blocks, which have absorbed a lot of human sweat over the years and are very hard to climb out of, with my son standing above me,” he says.

Here are the facts of how the past four years led him to this peculiar place: In 2020, while living in New York City, he entered rehab, for addiction to cocaine and a smorgasbord of pharmaceuticals. He and his wife, Anna Marie Tendler, split up. He relapsed. He went back to rehab, this time with the help of a starry intervention that has since passed into legend thanks to his Emmy-winning Netflix special, Baby J. This time, the sobriety stuck. Soon after, he connected with Munn and, soon after that, it became known that she was pregnant.

This cascade of revelations about his personal life came as a surprise to fans who thought they knew Mulaney better than they did. Some of those fans freaked out. Parasocial became the word of the moment.

Once Mulaney and Munn decided to raise their son together, Mulaney moved to Los Angeles where, among other things, he eventually produced the six-night fever dream of a talk-show experiment, John Mulaney Presents: Everybody’s in L.A., 12 new episodes of which are scheduled to air live on Netflix sometime in late February.

Inside the mall, we pass by jewelry and clothing stores; gift shops filled with dragon figurines and bobblehead Buddhas; a food court offering pho, congee, and plates of sea snails in various sauces. We find a bench near a stage with a banner wishing everybody a happy Tet Trung Thu, or Mid-Autumn Festival.

Another metaphor he likes, appropriate for his new Oklahoman family: “It was like a tornado picked me up, head to toe, hip to hip. And I landed somewhere extremely lucky and nice, where I’m having the best time in life.”

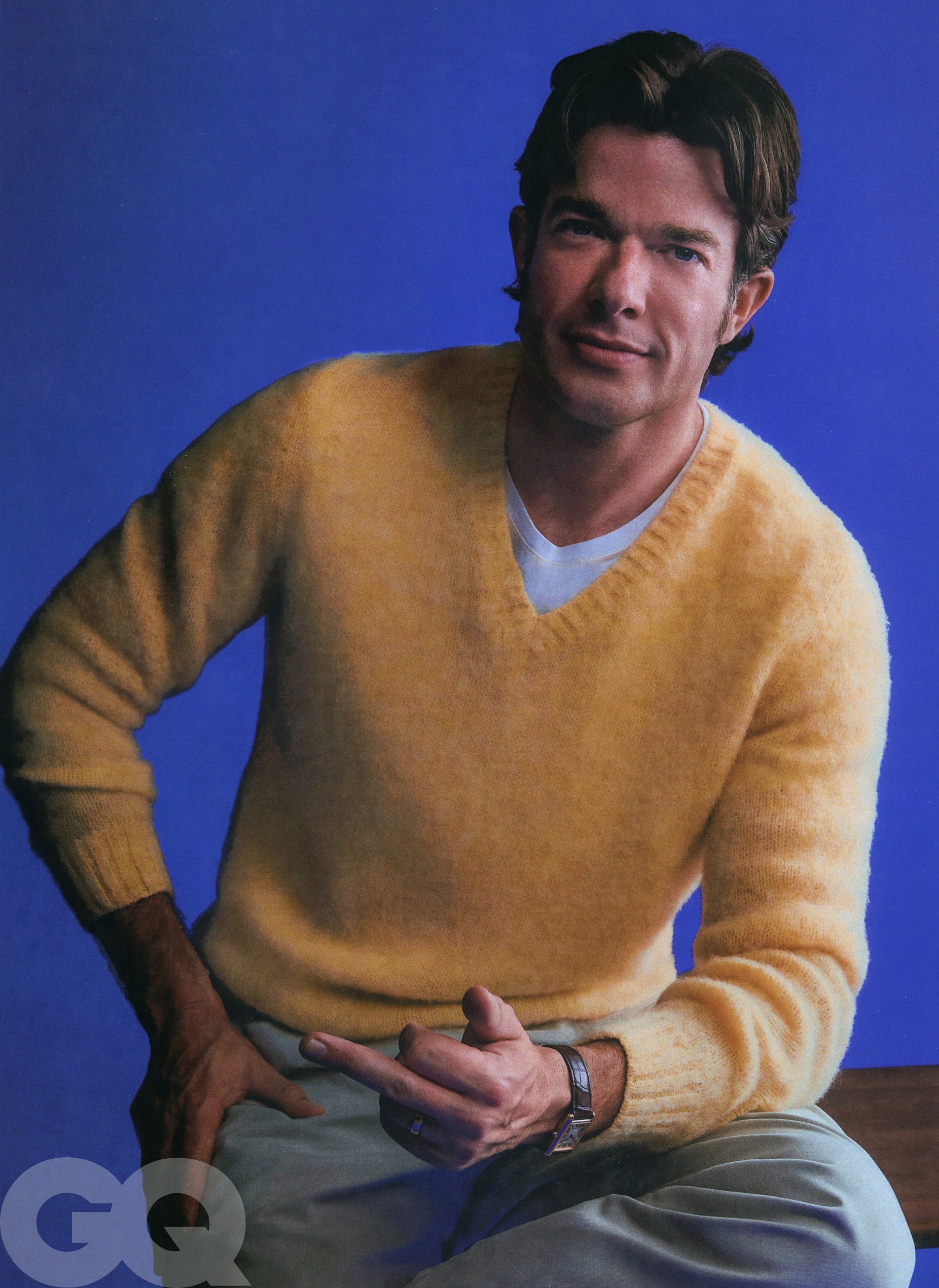

Indeed, if this is Oz, it seems to suit him. He has always been handsome, but time and sobriety have both softened and strengthened his features. Gone is the jangled angularity of a character in a hand-cranked Kinetoscope about to break into the Charleston. In its place, an unexpected superhero jaw. His old drug habits, as he describes them, were an exhausting back-and-forth of self-medication for a litany of supposed infirmities, more like biohacking than partying. But when the drugs went, so did the infirmities.

“There was a time when I would have told you that I could not fly, sleep, or perform unless I had a Klonopin,” he says. “I thought I had serious light sensitivity onstage. Spotlights had to be at a super-low grade. The front row had to be lit, because I thought I had a spatial…not vertigo, but something like that. I would have said, ‘It sucks, because I don’t always want to take Klonopin and Xanax, but I have to.’ ”

What about the ADHD he so often mentioned in his act? Funny thing: When he reluctantly allowed himself to be tested in rehab, he turned out not only to not have the condition but to possess “superior retention of facts and details.” This is something that would not surprise the audiences in front of whom he makes a habit of doing 10 tight minutes of site-specific material on Cincinnati or Biloxi or Charlotte while many touring comedians might hardly remember what city they are in.

Today happens to be Mulaney’s mother-in-law’s 69th birthday. Everybody calls Miss Kim “Miss Kim,” including her husband, to whom she has been married for nearly 25 years. She left Saigon with her mother and eight siblings in 1975. Miss Kim’s become something of a cult figure since she began popping up on Mulaney’s Instagram feed and in the stories he tells on talk shows. In August, she came along to an appearance on Late Night With Seth Meyers, where she stole the show while sitting in the audience. “If I did a perfectly accurate impersonation of my mother-in-law, it would be a career ender,” Mulaney acknowledged that night. That he eventually went for it and nevertheless avoided cancellation may be due in part to the affection between the two being so palpably genuine.

“John has seamlessly fit in with my mom and aunts in a way that I have never been able to,” says Munn, with a hint of an eye roll. “They love the same movies. They love the same Vietnamese gossip.”

Mulaney confirms, “Every day I can be like, ‘Have you talked to Phung today? Have you talked to Hoan? What’s going on with her cataracts?’ It’s my own reality show. A series that never ends.”

Munn calls the pair “the new Oh, Hello,” referring to the alter kaker duo that Mulaney and his college friend Nick Kroll periodically portray.

When I ask Miss Kim how she feels about her newfound fame, she makes it clear that there’s nothing new about it. “I am Olivia Munn’s mother!” she says, mock indignant, as she and Sam go off in search of T-shirts. The last time Mulaney hosted Saturday Night Live, he wore a shirt with Malcolm’s Chinese astrological sign, the golden ox. With another hosting gig coming up—his sixth—he wants one with Méi’s, the wood dragon.

Méi, who was born to a surrogate only 11 days ago, is impossibly fresh, hands still covered with tiny white mittens to prevent her from scratching herself. Mulaney lifts her gingerly from the stroller, like a bag of limes, supporting her neck as he reaches for a bottle of formula. “Méi, I am so…curious about you,” he tells her.

From the moment of Malcolm’s birth, in 2021, Mulaney has very publicly embraced fatherhood. “I’ve always been good at working with and for unreasonable people—people that are just against logic and the rules of time and space,” he says. “Malcolm sometimes feels like one of those bosses: ‘Why is your hair wet?? Make it dry!’ And I’m like, ‘That’s actually one of the more difficult things to do quickly!’ ”

In short, he seems like a happy man who is understandably eager to demonstrate his happiness. He’s allowed his hair to get longer and scruff to grow on his face. Nothing you might even notice on another face, but if you’re inclined to see facial hair as the most obvious way for men to externally broadcast internal change, it may be the most significant tonsorial development in comedy since David Letterman went full hillbilly. What it feels like is a sign that Kid Gorgeous, Baby J, the Comeback Kid, the wunderkind who is perpetually New in Town, has come into his manhood.

“I can be really set in my ways, in some ways,” Mulaney says. “But I am very good at major transformations.”

The first, as he tells it, came when he arrived in New York at age 23. Growing up in Chicago, he had told his parents early that he wanted to be a stand-up. At Georgetown University, he joined an improv group with Kroll and Mike Birbiglia. But, he says, “I had erratic work habits. I was very disorganized. In a sense I was always ambitious, but I wasn’t like, ‘I’m going to direct every play in high school.’ I wasn’t all over it in any way.”

In New York, a switch flipped. “I just hit the ground running. It was all of a sudden this total focus and drive to do as much stand-up as possible,” he says. “I didn’t drink alcohol anymore. I didn’t take any drugs. I was just totally dedicated to one thing, kind of monastically, and it was awesome.”

His comedic gifts—linguistic, physical, theatrical—are evident from his earliest performances. He is an excellent impressionist but deploys the gift almost casually, like a dagger he has the luxury of keeping strapped to his ankle. He is expert at leading an audience deep into the thicket of a joke’s setup and then pausing just long enough to allow them to arrive at the punch line right before he does. When it works best, a single word—say, gradually, in a segment of Baby J about his dismay at not being recognized in rehab—detonates like a bomb.

“He presents to the audience, ‘I am in control. I’m not particularly interested in which of these jokes you like and which you don’t, and no matter what happens, I am going to be having a very fun time,’ ” says Seth Meyers, describing what makes Mulaney such a good talk show guest (arguably the most perfect of his many talents) in terms that apply equally to his stand-up. “You just want to be on that ride with him.”

Mulaney auditioned for Saturday Night Live before the 2008–2009 season but did not make the cast. Instead, he got hired as a writer. Mulaney’s friend and frequent writing partner Simon Rich recalls watching his audition tape that year, before the staff convened—in particular, a bit deconstructing Law & Order extras. “I remember very distinctly thinking, I really, really hope that I get to write with this person,” Rich says. “Part of his genius is his precision and his absolute mastery of language. You never want to paraphrase a Mulaney joke, because they’re so perfectly constructed and crystalline. If you don’t get it word-perfect, you’re not doing it justice.”

Mulaney spent only four full seasons at SNL, but they remain a core part of his identity, even as the pervasive hold the show maintains on the American imagination amuses him. “We’re like the post office,” he says. “You hate us, but you love us. At the end of the day you go, ‘Look, they worked hard and got it done,’ but you groan at our existence. I have found that I will never need another topic to talk about. It’s like our World War II. At any event, any dinner I go to, anywhere in the world. This look comes into their eye as if you’re saying, ‘I’m an outlaw.’ Like, ‘Yeah, before this I was a cowboy.’ ”

Rich estimates that he and Mulaney, along with their writing partner Marika Sawyer, wrote some 250 sketches, including frequently taking on the host’s monologue, on the theory that it was one segment that could never be cut. He says it was Mulaney’s versatility that stood out. “He was able to write jokes that would allow every single cast member, and the host, to score, which is really hard,” he says.

So consummate a writer was Mulaney that Rich was almost surprised when he finally saw him perform his own stand-up: “I knew instantly that not only should this person be head writer of SNL someday, but this person should probably be a globally famous stand-up comic.”

The thought had crossed Mulaney’s mind too. In 2009 he was featured on Comedy Central Presents… and released an album titled The Top Part. In 2012 came the special New in Town. He had always thought of himself as part of an alternative-comedy scene that had a home at clubs like Pianos and Rififi in New York and Largo in LA but was ultimately relatively niche. “I didn’t feel like we were Black Flag or anything—and I was on the straighter edge of it—but it did feel like we were weirder than the norm,” Mulaney says.

Now though, he began to notice that he was getting just as big laughs on the road as he was in New York clubs. “I might’ve been in Madison, Wisconsin,” he recalls. “It was, like, 2013. It was older parents at the show with their teen kids, and they both seemed to enjoy it. I thought: This plays in the East Village, but it’s also working in Wisconsin. Maybe we should see how far we can push it.”

It was around this time that Mulaney started wearing a suit. There is something disorienting about going back to Mulaney’s early stand-up and finding him in a button-down shirt, oversized jeans, and sneakers. An aha moment came while headlining a club called Laughing Skull Lounge, in Atlanta, where all six comics on the bill wore that exact nerdy-white-guy outfit—and so did everyone in the crowd.

“I remember thinking, They paid money to see something. Why does it look like one of the audience members is standing onstage talking?” he says.

Suits do a lot of work in Mulaney’s story: as uniform, as shield, as plumage, and as camouflage. He is reminded of his son’s recent fascination with Elvis, especially the 1968 NBC Comeback special in which Presley appears, resplendent, in head-to-toe leather. “There’s something about someone who’s like, I’m the entertainer here,” he says. Indeed, one can draw a line from Elvis’s getup to Eddie Murphy’s leather outfits in Delirious and Raw to Mulaney’s maroon suit in Baby J—with, he points out, Richard Pryor’s red tuxedo from Live on the Sunset Strip somewhere in between.

Those sorts of names are helpful in grasping the shape of Mulaney’s ambition. “I consciously thought, What if you did Spalding Gray with the energy of Bernie Mac?” he says. “What if what you were saying was really confessional and had an edge to it; the language was specific and nuanced; it was personal and contradictory, dark, suicidal, whatever it was—but you kept selling it with this big showbizzy energy. How big could I scale it? How big can you sell weird and specific?”

The merging of stand-up with what we once would have called “one-man shows”—and its attendant confusions—is hardly limited to Mulaney. But his work proved to be an especially well-crafted Trojan horse for smuggling the Performing Garage into the Hollywood Bowl. In 2015’s The Comeback Kid, he delivers an extended set piece about going with his mother to meet Bill Clinton, who had been a Yale classmate of both his parents. It is, as he points out, not the most universally relatable story.

“I’m just going to see,” he says he thought. “I’m going to see if you can do a nine-minute story about this and just hit it as though you’re doing the best bit about dating ever. I’m going to tell this long story about how my parents had a complicated relationship with the Clintons, and how it sort of plays into how me and my dad relate to each other, and I am going to go onstage and fucking annihilate with it.”

Baby J, conversely, played a shadow version of the same trick. “It’s like: Okay, this is the most confessional one, so it’s going to be all jokes,” he says. “There is no moment that isn’t supposed to be very entertaining.”

Spalding Gray, who died by suicide in 2004, remains a North Star for Mulaney and an open influence. Gray’s widow, Kathie Russo, gifted Mulaney the pull-down map of Southeast Asian bombings Gray used in his breakthrough monologue, Swimming to Cambodia, a prop that Mulaney paid tribute to in Everybody’s in L.A. He says he modeled the rhythm of one of his more memorable early story-jokes, about being mistaken for a stalker in the subway, on Gray’s description of skiing down a mountain in his monologue It’s a Slippery Slope.

As it happens, that show is in part about Gray leaving his wife—who had been a longtime presence in his work and whom audiences had reason to believe they knew—to suddenly start a family with Russo. “It borders on extremely unlikable,” Mulaney told Pitchfork in 2018 for a list of his favorite comedy albums. He recalled Gray telling Terry Gross at the time that he was not a nice guy. “Not a lot of people will admit that,” he said. “And maybe more people should.”

By every account, Mulaney is a nice guy. It’s hard to imagine a person more lavishly friended up—particularly in what are supposedly the schadenfreude-soaked worlds of comedy and entertainment, not to mention drug addiction. In the deeply intertextual universe of modern comedy—in which events appear first as reality, then as a talk show bit, then part of a special, on a podcast, in a fictionalized meta-show, an animated version of a fictionalized meta-show, and so on—his intervention, featuring the likes of Kroll, Meyers, Fred Armisen, and Natasha Lyonne, has taken on such a level of romance that people openly wish they had been there. (“It was not funny,” Kroll had to pointedly correct the comic Bert Kreischer while on his podcast.) Mulaney’s post-rehab tour of late-night shows was like a seminar on supportive, sensitive masculine friendship: He and Stephen Colbert waxed philosophical about A Man for All Seasons; he and Meyers exchanged “I love you”s.

Mulaney swears he has non-comedian friends—the constitutional lawyer and onetime acting solicitor general Neal Katyal, for one—and even some that aren’t famous. But, he says, “I have more in common with every comedian than I do with any other person.”

“John is a very good friend. He’s a thoughtful person and I think that his group of friends reflect that type of human being,” says Jimmy Kimmel, in whose guest house Mulaney briefly lived after leaving rehab in 2021 and with whom he is on several group texts, including one “almost exclusively about the band Kiss and their merchandising opportunities.” Upon leaving, Kimmel says, Mulaney left a framed photo of himself as a thank-you gift. When Méi was born, Mulaney texted Kimmel asking how much he should tip the hospital security guards.

“I do have that sunnier, cornier side,” Mulaney says. “I really have said hello to balloons before.”

At the same time, for all of its tour de force comedy, Baby J did have a couple of barbed thesis statements. One was: “Likability is a jail.” The other was: “Don’t believe the persona.”

Mulaney declines to talk about his first marriage; he is also conspicuously absent from Tendler’s memoir, published earlier this year. Of the period of tabloid fever in the year after it ended, he says, “You might think this is bullshit, but it feels very distant.”

(In retrospect, Mulaney’s old bits about matrimony were straight out of the borscht belt, a place where, legendarily, “marriage isn’t a word, it’s a sentence.”)

The whole thing was a lesson in the ruthlessness of appearances: Take away the suit, the haircut, all the other affects of a former altar boy, and perhaps more people would have noticed that Mulaney’s act was as drug soaked as a 1970s Stones record. The very first track of his first comedy album was titled “Blacking Out and Making Money.” Surely, there was a kind of willful blindness at work.

What he says about it is this: “I very much tried to tell everyone.”

But wasn’t he also trying to hide his darker tendencies, I ask. Didn’t he make a habit of telling us exactly how harmless he was, just in case our first impressions weren’t convincing enough? From The Comeback Kid: “I’m so open and vulnerable, I look like a doll that you point out molestation on.” From New in Town: “I look like I was just sitting in a room in a chair eating saltines for, like, 28 years.”

“What I said,” he interrupts me to say, “is that I look harmless.”

A few years into his career, Mulaney had the nagging thought that he wished he’d started out with a stage name. “I don’t like when they say the same name that I had when I was 10. I don’t always like reading that name out there,” he says. “I wonder if it’s nice, when you see ‘so-and-so sucks,’ you go, ‘That’s not me, actually.’ I always wondered if that helped performers be like, ‘I’m not Dean Martin. So be mad at that thing all you want.’ ”

I say that it sounds like another way to insist that the person who is on stage performing is not actually him.

“Except, and this is the problem,” he says. “That is also the person who is the most me.”

Olivia Munn’s favorite story about Mulaney and his father, Charles W. Mulaney Jr., involves John, at seven or eight, begging to take his father’s old briefcase to use as a school bag. “I said, ‘Dude, did all the kids make fun of you?’ ” she says. “And he said, ‘No. The next day they all had them too.’ ”

The elder Mulaney, a corporate lawyer, is the other persona who runs through Mulaney’s work, a formidable embodiment of adult responsibility that Mulaney simultaneously idolizes and resents. The classic Charles story, from The Comeback Kid, involves taking the family through a McDonald’s drive-through on a road trip, ordering a single black coffee for himself, and driving on. When Mulaney first told his father that he wanted to be a stand-up comedian, Charles’s response was confusion: “Best-case scenario, you’re like what, Steve Martin?”

Mulaney says his father’s attitude has since evolved. “I think he enjoyed seeing, ‘Oh, it’s a thing people do respect,’ which was fun for me to watch. I didn’t need them to suddenly become stage parents or love everything I say or even think that comedy’s important, or some shit. I don’t need that,” he says.

Either way, it’s another data point about suits—i.e., why putting one on to go to work might have had particular appeal for this particular comedian. And then there’s what Munn says Mulaney told her, shortly after they decided to have their first baby together: “He said, ‘I want to come home and wear a suit every day. I want him to see his father come in and wear a suit and be proud of how he presents himself to the world.’ ”

The day after exploring Little Saigon, we are at Mulaney and Munn’s new house in Orange County. There are a few extra couches standing around, but otherwise the family seems to be settling in to their new digs nicely. Munn is feeding Méi a bottle. Malcolm rolls around in front of Inside Out before dragging himself away to join the adults at the table. Miss Kim is getting great pleasure out of cutting up a durian, the notoriously stinky fruit, which she picked up at the grocery near Asian Garden Mall, and watching the family’s range of reactions from intrigued to disgusted.

Mulaney and Munn had met just once (at Seth Meyers’s 2013 wedding) before reconnecting in early 2021. Mulaney had left rehab and was casting around for a new place to live in New York. Munn referred him to a friend; he sent thanks. The ensuing relationship, such as it was, was brief. If the tabloids thought they had a scoop about them dating, the joke was on them, because it was never true: They were just having a baby.

“It wasn’t anything close to ‘dating,’ ” Munn says. “I barely knew him.” Still, when she told Mulaney she was pregnant, she says, he was immediately eager for her to have the baby. “It wasn’t necessarily ‘We’re going to be married and live together’ or any of that, but it was ‘I will be involved in some way.’ ” Munn assumed they would co-parent. For most of the pregnancy, she lived in LA while Mulaney was in New York. Every few weeks they would talk or he would visit.

Mulaney can seem weary, if not a little irritated, to be still talking about his drug problems. After all, it’s been four years since his intervention and another several years of talking about it in the material that grew into Baby J. But one of the unintended consequences of his “just jokes” strategy in that special may have been leaving an empty space in the public mind about where the suffering took place.

From our point of view, one moment he was clean and the next time we saw him he was…clean! And being pretty funny about it. Even the notorious GQ interview that Mulaney ended the show reading from, saying he had no memory of doing it, turned out to be pretty good! Mulaney breaks down the legal doctrine governing parody. He comes up with a good idea for a talk show interviewing old people. He makes a poignant point about COVID increasing compassion and ends on a good joke. If rock bottom is eating Froot Loops while giving sparkling quotes, one might think, I’ll take it.

Mulaney politely but firmly makes it clear that this is very stupid. He tells a story about doing so much cocaine in his New York apartment one night that he was afraid he would die, but also felt unable to go to the urgent care next door. “I left the door to my apartment open. I can’t explain the logic, but I was going to hit the door buzzer and tell the doorman to run and get the paramedics. I think I was worried I wouldn’t be able to dial and explain, and I didn’t want them to have to break the door down. I just sat on the rug and slowly came down. And I thought, Okay, this is insane. I’m going to totally slow down. That was like a Tuesday. And Thursday night, I did it again.”

In the years since, he has been asked to participate in several other people’s interventions, and he finds himself having to manage the expectations of the interveners. “I’m not saying don’t do it, but define your goals here,” he tells them. The important thing, in the moment, is to simply stop the person from dying. “But that will not immediately mean that you like them again right away, or that they are okay with you.”

Munn fills in some more of the picture of Mulaney’s own post-rehab period. “It was like watching a man in a tsunami,” she says. “I was watching someone newly sober, at the edge of a cliff, and I didn’t know him well enough to help him.” He told her that he was afraid he would relapse. The troubles, though, never seemed to be about the coming baby. “That’s the one thing that made him seem light and happy. I remember he was really excited to tell his parents.”

Occasionally, she would go to see him perform. “In my head, I’m thinking, I don’t know really what’s happening with this guy. It feels pretty shaky,” she says. “But then I would see him at the Troubadour and be like, ‘Man, he’s on fire. He’s just that phenomenal.’ ”

When she was about six months pregnant, Munn says, she staged a mini-intervention of her own, getting more involved in his recovery but still not sure what shape the relationship would take. The two agreed that Munn would give him random drug tests, a ritual they still practice. “It’s like a relief,” he says. “I like to be able to not even have that be a question in her or anyone else’s mind. Something about peeing in that cup is like, I’m walking this walk. It gives me confidence.”

It was only two months before Malcolm was born that the two decided that they would attempt to raise him as a couple.

It amuses Mulaney that Malcolm is growing up a California kid. “His hair curls in the California air,” he says. “When we’re in Chicago, he has straight little John Mulaney hair. Until my late 20s, Malibu was a funny word to me. It was like saying Zanzibar.”

He and Malcolm recently spent a day driving around Los Angeles, checking out potential soundstages for the new edition of Everybody’s in L.A. The exact name is still being debated—there may be a “Live” thrown in there—but Mulaney says the rest of the show will be the same, down to Richard Kind acting as sidekick: a fascinating, purposefully messy attempt to illuminate his new home that is equal parts Tonight Show, Jerry Lewis telethon, and City of Quartz.

“Doing the show really made me enjoy LA,” he says. “Something clicked where I was like, ‘Oh, this feels like the future.’ There’s so much going on: aerospace, shipping, agriculture, industry. This Hollywood thing is pretty tiny.” He says Jonathan Gold, the late Pulitzer Prize–winning food critic and LA lifer who once set out to visit every restaurant along the 15.5-mile length of Pico Boulevard, was an inspiration.

Mulaney is intent on preserving the chaotic energy of the show’s first six-episode run. “There’s a quote I heard about Edward Hopper, that he was a great artist but he was only a good painter. But if he had been a better painter, he would have been a worse artist,” he says. “I sort of feel like if we tried to make the show better, it would be worse.”

How does one manage that?

“You go on instinct over data and recklessness over planning,” he says.

Certainly, the show is part of the ongoing attempt of seeing how far one can scale weird. If there’s a godfather of that artistic project, it’s David Letterman, clearly one of Mulaney’s kindred spirits. Backstage at Everybody’s in L.A. in May, Letterman gave Mulaney some advice: “He said, ‘When you’re running The Weird Show, you have to be the least weird person on it,’ ” Mulaney says. “ ‘Everybody’s going to be saying, ‘Let’s do this,’ and ‘Let’s do that,’ and you’re the one having to modulate the gas and brakes.’ ”

Maybe Mulaney’s biggest achievement is making you believe that a 20th-century big-tent job like talk-show host still matters. And there are few he hasn’t either done or been offered, at least that don’t involve calling NFL games. He has been asked twice to host The Daily Show, once when Jon Stewart left and again more recently, but said no both times. Likewise to an offer to host the 2025 Oscars. It seems a given that at some point the question of sliding behind one of the networks’ late-night desks will be on the table.

This December he will return to New York for a five-week run in Simon Rich’s Broadway show, All In: Comedy About Love, alongside a cast of Kind, Armisen, Renée Elise Goldsberry, and others. The show is based on Rich’s short stories, many of them first published in The New Yorker, and features music by Stephin Merritt of the Magnetic Fields and projections by cartoonist Emily Flake. Brooklyn may simply implode.

For now, though, a few more moments of domestic tranquility. Miss Kim brings over a plate of grilled-beef spring rolls and handmade Chinese boiled dumplings called sui jao. Méi is asleep, swaddled, on a cushion on Sam’s lap. Miss Kim goes off to talk to one of her family members back home, a plastic container of durian under her arm.

“Maybe John Durian would have been a good stage name,” Mulaney will text the next day. “It’s a little like Bobby Darin and a little like John DeLorean.” For now, America’s favorite comedian trails after his mother-in-law, anxious above all for the latest news on the cataract surgery of one Ms. Hoan Nguyen of Oklahoma City.

Brett Martin is a GQ correspondent.

A version of this story originally appeared in the 2024 GQ Men of the Year issue with the title “Kid Gorgeous Grows Up”

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

Photographs by Eli Russell Linnetz

Styled by Jon Tietz

Hair by Thom Priano for R+Co Bleu

Skin by Holly Silius using Retrouvé

Tailoring by Yelena Travkina

Set design by James Rene

Produced by Tightrope Production