Dissecting One of APT29's Fileless WMI and PowerShell Backdoors (POSHSPY)

Mandiant

Written by: Matthew Dunwoody

Mandiant has observed APT29 using a stealthy backdoor that we call POSHSPY. POSHSPY leverages two of the tools the group frequently uses: PowerShell and Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI). In the investigations Mandiant has conducted, it appeared that APT29 deployed POSHSPY as a secondary backdoor for use if they lost access to their primary backdoors.

POSHSPY makes the most of using built-in Windows features – so-called “living off the land” – to make an especially stealthy backdoor. POSHSPY's use of WMI to both store and persist the backdoor code makes it nearly invisible to anyone not familiar with the intricacies of WMI. Its use of a PowerShell payload means that only legitimate system processes are utilized and that the malicious code execution can only be identified through enhanced logging or in memory. The backdoor's infrequent beaconing, traffic obfuscation, extensive encryption and use of geographically local, legitimate websites for command and control (C2) make identification of its network traffic difficult. Every aspect of POSHSPY is efficient and covert.

Mandiant initially identified an early variant of the POSHSPY backdoor deployed as PowerShell scripts during an incident response engagement in 2015. Later in that same engagement, the attacker updated the deployment of the backdoor to use WMI for storage and persistence. Mandiant has since identified POSHSPY in several other environments compromised by APT29 over the past two years.

We first discussed APT29’s use of this backdoor as part of our “No Easy Breach” talk. For additional details on how we first identified this backdoor, and the epic investigation it was part of, see the slides and presentation.

Windows Management Instrumentation

WMI is an administrative framework that is built into every version of Windows since 2000. WMI provides many administrative capabilities on local and remote systems, including querying system information, starting and stopping processes, and setting conditional triggers. WMI can be accessed using a variety of tools, including the Windows WMI Command-line (wmic.exe), or through APIs accessible to programming and scripting languages such as PowerShell. Windows system WMI data is stored in the WMI common information model (CIM) repository, which consists of several files in the System32\wbem\Repository directory.

WMI classes are the primary structure within WMI. WMI classes can contain methods (code) and properties (data). Users with sufficient system-level privileges can define custom classes or extend the functionality of the many default classes.

WMI permanent event subscriptions can be used to trigger actions when specified conditions are met. Attackers often use this functionality to persist the execution of backdoors at system start up. Subscriptions consist of three core WMI classes: a Filter, a Consumer, and a FilterToConsumerBinding. WMI Consumers specify an action to be performed, including executing a command, running a script, adding an entry to a log, or sending an email. WMI Filters define conditions that will trigger a Consumer, including system startup, the execution of a program, the passing of a specified time and many others. A FilterToConsumerBinding associates Consumers to Filters. Creating a WMI permanent event subscription requires administrative privileges on a system.

We have observed APT29 use WMI to persist a backdoor and also store the PowerShell backdoor code. To store the code, APT29 created a new WMI class and added a text property to it in order to store a string value. APT29 wrote the encrypted and base64-encoded PowerShell backdoor code into that property.

APT29 then created a WMI event subscription in order to execute the backdoor. The subscription was configured to run a PowerShell command that read, decrypted, and executed the backdoor code directly from the new WMI property. This allowed them to install a persistent backdoor without leaving any artifacts on the system’s hard drive, outside of the WMI repository. This “fileless” backdoor methodology made the identification of the backdoor much more difficult using standard host analysis techniques.

POSHSPY WMI Component

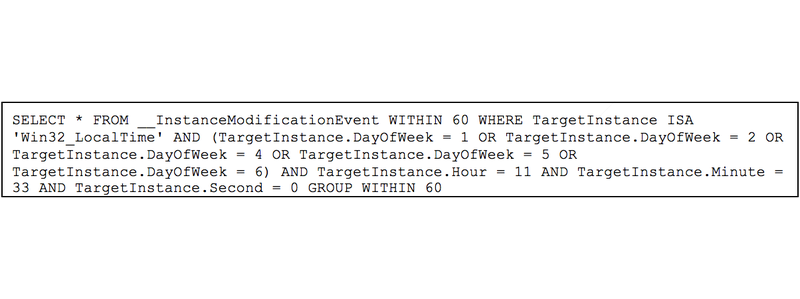

The WMI component of the POSHSPY backdoor leverages a Filter to execute the PowerShell component of the backdoor on a regular basis. In one instance, APT29 created a Filter named BfeOnServiceStartTypeChange (Figure 1), which they configured to execute every Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday at 11:33 am local time.

Figure 1: “BfeOnServiceStartTypeChange” WMI Query Language (WQL) filter condition

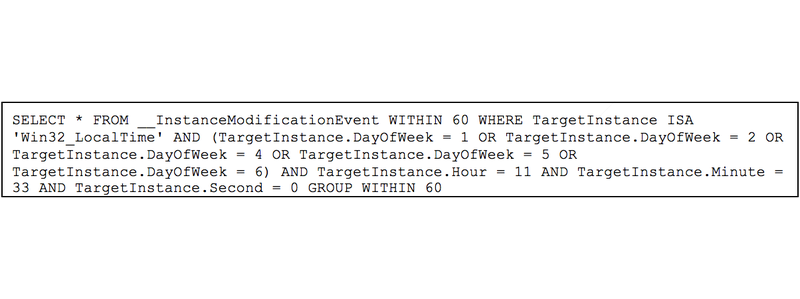

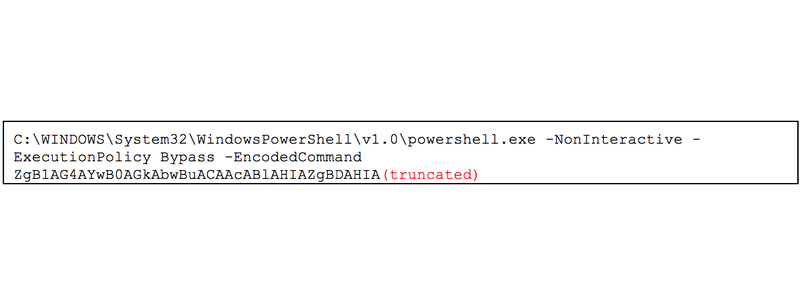

The BfeOnServiceStartTypeChange Filter was bound to the CommandLineEventConsumer WindowsParentalControlsMigration. The WindowsParentalControlsMigration consumer was configured to silently execute a base64-encoded PowerShell command. Upon execution, this command extracted, decrypted, and executed the PowerShell backdoor payload stored in the HiveUploadTask text property of the RacTask class. The PowerShell command contained the payload storage location and encryption keys. Figure 2 displays the command, called the “CommandLineTemplate”, executed by the WindowsParentalControlsMigration consumer.

Figure 2: WindowsParentalControlsMigration CommandLineTemplate

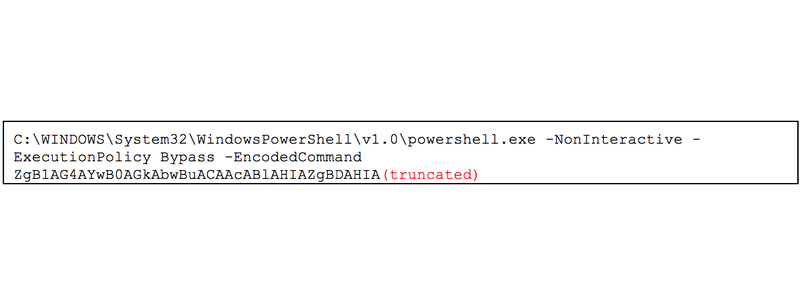

Figure 3 contains the decoded PowerShell command from the “CommandLineTemplate.”

Figure 3: Decoded CommandLineTemplate PowerShell code

POSHSPY PowerShell Component

Here is the full code for a POSHSPY.

The POSHSPY backdoor is designed to download and execute additional PowerShell code and Windows binaries. The backdoor contains several notable capabilities, including:

1. Downloading and executing PowerShell code as an EncodedCommand

2. Writing executables to a randomly-selected directory under Program Files, and naming the EXE to match the chosen directory name, or, if that fails, writing the executable to a system-generated temporary file name, using the EXE extension

3. Modifying the Standard Information timestamps (created, modified, accessed) of every downloaded executable to match a randomly selected file from the System32 directory that was created prior to 2013

4. Encrypting communications using AES and RSA public key cryptography

5. Deriving C2 URLs from a Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) using lists of domain names, subdomains, top-level domains (TLDs), Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs), file names, and file extensions

6. Using a custom User Agent string or the system's User Agent string derived from urlmon.dll

7. Using either custom cookie names and values or randomly-generated cookie names and values for each network connection

8. Uploading data in 2048-byte chunks

9. Appending a file signature header to all encrypted data, prior to upload or download, by randomly selecting from the file types:

- ICO

- GIF

- JPG

- PNG

- MP3

- BMP

The sample in this example used 11 legitimate domains owned by an organization located near the victim. When combined with the other options in the DGA, 550 unique C2 URLs could be generated. Infrequent beaconing, use of DGA and compromised infrastructure for C2, and appended file headers used to bypass content inspection made this backdoor difficult to identify using typical network monitoring techniques.

Conclusion

POSHSPY is an excellent example of the skill and craftiness of APT29. By “living off the land” they were able to make an extremely discrete backdoor that they can deploy alongside their more conventional and noisier backdoor families, in order to help ensure persistence even after remediation. As stealthy as POSHSPY can be, it comes to light quickly if you know where to look. Enabling and monitoring enhanced PowerShell logging can capture malicious code as it executes and legitimate WMI persistence is so rare that malicious persistence quickly stands out when enumerating it across an environment. This is one of several sneaky backdoor families that we have identified, including an off-the-shelf domain fronting backdoor and HAMMERTOSS. When responding to an APT29 breach, it is vital to increase visibility, fully scope the incident before responding and thoroughly analyze accessed systems that don't contain known malware.

Additional Reading

This PowerShell logging blog post contains more information on improving PowerShell visibility in your environment.

This excellent whitepaper by William Ballenthin, Matt Graeber and Claudiu Teodorescu contains additional information on WMI offense, defense and forensics.

This presentation by Christopher Glyer and Devon Kerr contains additional information on attacker use of WMI in past Mandiant investigations.

The FireEye FLARE team released a WMI repository-parsing tool that allows investigators to extract embedded data from the WMI repository and identify WMI persistence.