When 23-year-old Gabriela Rossner was in high school, she experienced an accident that dislocated her spine, leaving her with pain and mobility impairment.

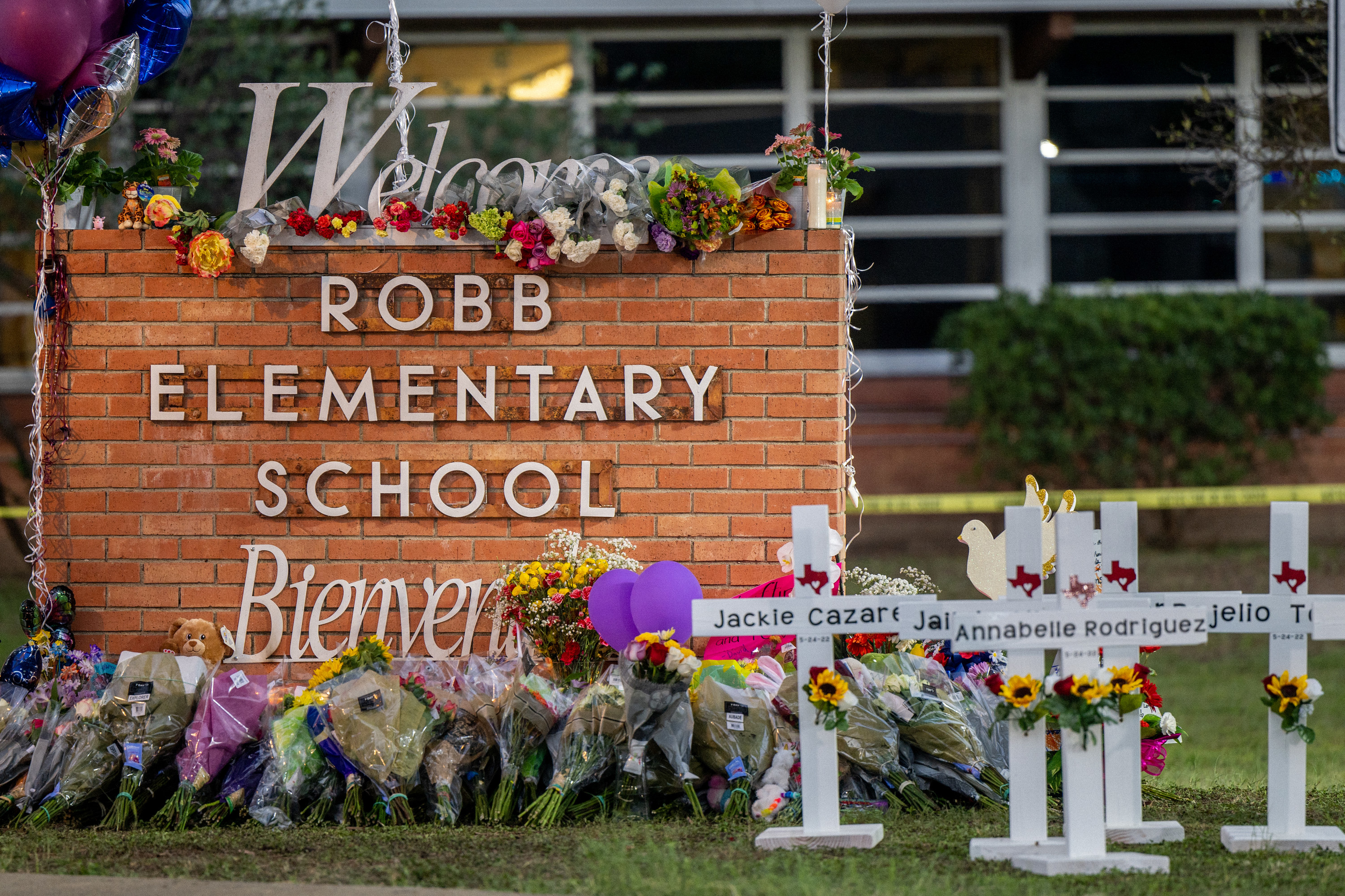

Recently, in light of the tragic shooting that took place at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas and the criticism local police now face as parents and the surrounding community question their responsiveness, Gabriela took to Twitter to reflect on emergency protocols in schools as they relate to children with disabilities and their relationship with the police.

It’s already been said, but the emergency ‘plan’ for disabled kids is to let us die. Not even in active shooter scenarios, but also fires. My most poignant example happened when I was in the AAPD intern class of 2019 and campus cops left us for an hour during a 3am fire alarm 🧵

She recalled a night in 2019 when she and her fellow interns for the American Association of People with Disabilities were staying in university-hosted dorms and the fire alarm started going off around 3 a.m. "Twenty disabled kids [were] on the third floor," she said. "We all work together to evacuate, and a group of us with mobility issues go to the stair landing. That’s the plan always — go to the hopefully fire insulated stairway and wait for help."

After attempting to report their location to a 9-1-1 operater, Gabriela said, "Thirty minutes pass, we see about 600 kids evacuate past us and then it’s eerily quiet except the ongoing alarm of course. We still don’t know if it’s a real fire or not, and at this point begin making plans to help each other down — literally by butt scooting step by step."

"The first cop shows just as my friend is about to abandon her wheelchair, 45 minutes in," she continued. "Doesn’t make eye contact with us, says into his walkie talkie, 'There’s a group of cripples stuck on the 3rd floor landing.' Then he WALKS AWAY down the stairs and leaves us there as we yell."

Later on, "I find a cop who yells at me for not evacuating. I say that me and five other disabled kids have been in the stairs for over an hour, and she is surprised. This cop confirms it’s a false alarm, and says we can go back to our rooms."

"This event was extremely traumatizing, even though there was never a real fire, because it showed so clearly that the ‘safety plans’ are shit and the cops clear disregard for the lives of disabled people. We keep each other safe," she concluded.

Whereas other students have been seen escaping via windows during school emergencies or evacuating down stairs, students with mobile impairments are not always physically capable of doing so — which has led to lawsuits, like the one in New Jersey when a student who uses a wheelchair was left inside while the fire alarm went off. According to officials involved, the school "did not have policies for evacuating students with disabilities."

This lack of consideration toward students with disabilities is exactly Gabriela's point of frustration. She told BuzzFeed: "There [is] a lot of talk about safety plans and drills and emergency preparedness, but a clear oversight of disabled students. ... These safety plans do not give disabled students a fighting chance to make it out of an emergency alive when the pre-determined plan is always to 'wait in place and first responders will come to you.'"

"Disabled students need to be thought of in the PLANNING stages when thinking about school emergencies," she continued. "It is clear that the people who made the 'shelter in place and wait for rescue' plan have never actually been in the position themselves. All parts of it are awful — waiting in place during an emergency means you might die while you wait, be it from bullets, fire, or natural hazards."

"When discussing school-located emergencies, it's important to remember that disabled students are everywhere and must be acknowledged in every aspect of planning, especially in regards to active shooters. Suggestions like limiting the number of doors to a school should be recognized as actively harmful to disabled students."

Gabriela is right. According to Pew Research, there are almost 7 million students with disabilities in the US, and each deserves a plan to ensure their safety.

"I have been a disabled kid during an active shooter drill," she said. "The previous semester, my dorm building had actually caught on fire and I waited in my room per instructions from the disability office that 'someone would come to get me, my name was on a list.' No one ever came. ... After my friends evacuated me, one of them went to tell the fire marshal they had gotten me out and I didn't need to be rescued; the fire marshal had no clue what he was talking about."

"So even though I was told the plan was that my name was on a list somewhere with first responders, first responders had no knowledge of [my] evacuation needs."

During her own emergency experience, Gabriela remembered feeling "disposable" and "subhuman" as others rushed to safety while she and her group were left behind. With this in mind, and as reports of mass shootings have continued to roll out after Uvalde, the 23-year-old hopes more consideration for these students is taken sooner rather than later.

The Senate has currently stalled two gun control bills that aim to make background checks for owning firearms more extensive. Please take action on gun violence, call your senator! Here are 11 other ways you can take action to stop gun violence in the US.