How Pepe Aguilar Turned Singing On Horseback Into Arena Gold

As a toddler, he watched his parents popularize ranchera music in the U.S. Now, he's updating the Mexican folk equestrian show as an ambitious touring production — and making it a family affair.

Pepe Aguilar likes to meditate. For nearly 15 years, time permitting, he has done it first thing in the morning for at least 15 minutes. He says it’s part of his journey — along with working with a life coach — to become more present. It’s also the time when, one day in 2017, Aguilar had one of his best ideas.

In the 1960s, Aguilar’s revered musician parents — ranchera singer-songwriter, producer and actor Don Antonio Aguilar and singer-actress Flor Silvestre — pioneered Mexican folk equestrian shows that mixed concert-style sets and traditional jaripeo performances, which feature regal dancing horses and elaborate cowboy stunts. The events helped popularize ranchera in the United States, and in the midst of his meditation, Aguilar envisioned producing a modernized version of them.

After jotting down some thoughts, he excitedly called his mother to share his concept. “Ay mijito, just let me know when you’ve advanced on this idea of yours because, right now, you’ve got a long way to go,” she told him. It wasn’t quite the response he had hoped for. But Silvestre was right. Aguilar’s vision would require extraordinary effort, and he’d need the right people by his side. (Silvestre died in 2020, Don Antonio Aguilar in 2007.)

Trending on Billboard

“All I wanted was to offer something different in my shows,” the 54-year-old pop, ranchera and mariachi star explains on Zoom from his Houston home. “I was touring in arenas, theaters, I was happy. But I wasn’t happy from a creative standpoint. After meditating that day, it was like a download of ideas that led to culture, mexicanidad [Mexican identity], charrería [rodeo] — all of that is what really makes me who I am. Why have I been trying to be like Madonna or some sort of rock star for 20 years? What I’m doing now feels natural.”

Aguilar has been performing since he was a toddler, when he joined his parents and brother, Antonio Aguilar Jr., on the road for family jaripeos and made his debut at New York’s Madison Square Garden at age 3. Early in his career, he left his comfort zone and began singing in rock bands before opting for more traditional sounds with pop influences. Eventually, he followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a renowned singer-songwriter and producer of ranchera and mariachi music.

To execute such a complex tour, Aguilar had to start from scratch, searching for horses (Andalusian, Spanish, Quarter), special acts (acrobats, strongmen), bull riders and charros (skilled riders and ropers). But his background gave him a solid foundation. “I was literally born into this, but when I was part of my father and mother’s show, I wasn’t aware of the magnitude and the importance of what they were doing,” Aguilar says. He spent a year assembling a team of creative directors (including one producer from Cirque du Soleil and Formula 1) before officially launching the tour in January 2018.

The family tour that Aguilar created, Jaripeo Sin Fronteras (Jaripeo Without Borders), is a concept he hopes his own children, artists Ángela and Leonardo Aguilar, will one day carry on. Now in its fourth year, the trek — which includes back-to-back sets by Pepe, Ángela and Leonardo, and brother Antonio Jr. (all singing on horses), circus-like acts during intermission, charrería competitions and bull-riding — continues to hit new markets and will wrap Nov. 19 in Zacatecas, Mexico.

A joint effort between producing partner Live Nation and Pepe’s own promotion company, Pepe Aguilar Presents, the tour has traveled from coast to coast with a 120-person production team, eight horses and bulls, 40 musicians, a strongman from Mongolia nicknamed Pulga, performers dressed as Aztec warriors in $50,000 costumes, professional charros who perform equestrian acrobatics and, of course, the Aguilars. “This isn’t your typical concert,” Pepe says. “It’s a very weird, different animal.”

A weird, different animal — but also a lucrative one. Since its 2018 debut, Jaripeo Sin Fronteras has grossed $40.1 million from 409,000 sold tickets across 53 shows, including $19 million from 21 shows since the tour restarted post-pandemic in September 2021, according to Billboard Boxscore. Not that it’s inexpensive or without risks.

“It’s more than any economics Ph.D. would tell you to invest in,” Pepe says with a smirk. “But I’m not doing this just for the money. The idea is to dignify our culture and make people feel proud of our mexicanidad. That can’t be cheap. Being the promoter, the risk is very high. We’re talking thousands and thousands of dollars in expenses. And, for this thing to make sense, the shows need to be packed. But I trust in the concept, and I totally believe in my culture. For me, it’s a safe bet; for everyone else, like my associates — they’re dying [of stress] all the time.”

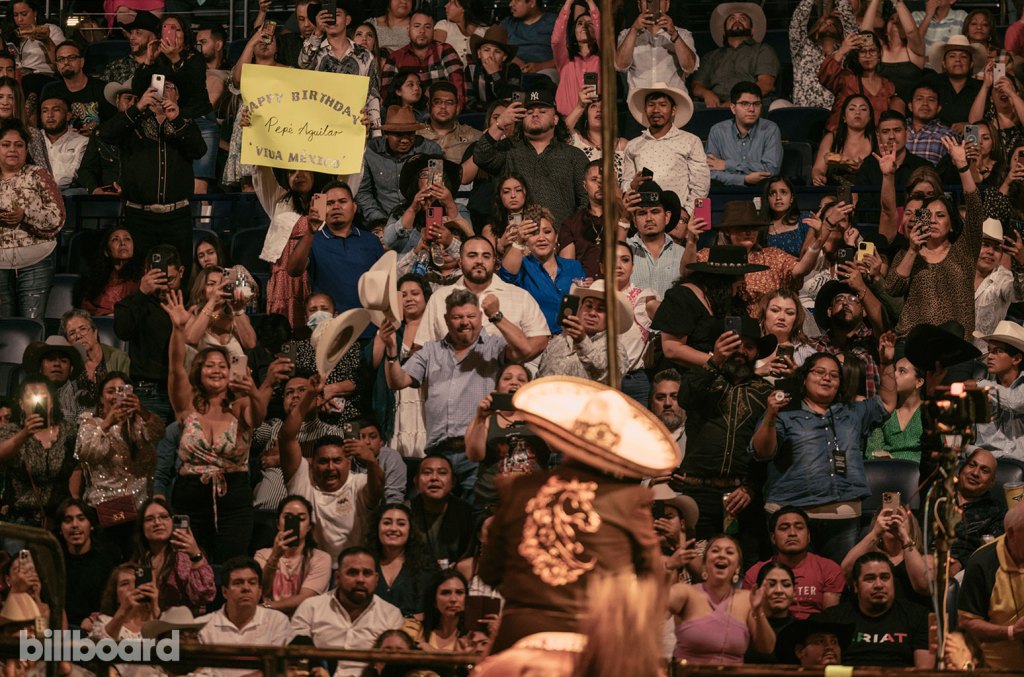

On Aug. 7, Aguilar and his family were preparing to begin their 2022 touring in Nashville. Fans of all ages, including families decked out in cowboy hats and pointy boots, patiently waited outside Music City’s Bridgestone Arena. When they got inside, they found one of the most ambitious arena productions around.

Jaripeo Sin Fronteras is the product of painstaking calculation. At its center is an oval-shaped stage, three-quarters full with 650 tons of dirt, laid approximately eight feet high so horses can gallop in. The production team loads in the 118-by-70-foot ring with the dirt (along with the chutes and railings lining it) at midnight day of show. By 8 a.m., they’ve installed the show’s lighting, special effects and sound systems. Horses and bulls arrive around midday, and musicians get to the venue two hours later to rehearse. Those 40 musicians will occupy the platform on the remaining quarter of the stage, each playing their instruments for their respective genres (mariachi, banda, norteño) and remaining for the entire show, which runs nearly four hours.

“I had total faith in the production of this tour because Pepe is so invested in the concept and he’s very hands-on,” says Emily Simonitsch, senior vp of talent at Live Nation. “Probably one of the biggest challenges is describing to the venues’ personnel that are not familiar with jaripeos what it all entails. They think we need two or three days to load in the dirt, but we don’t. There are so many details, so we had to educate venues.”

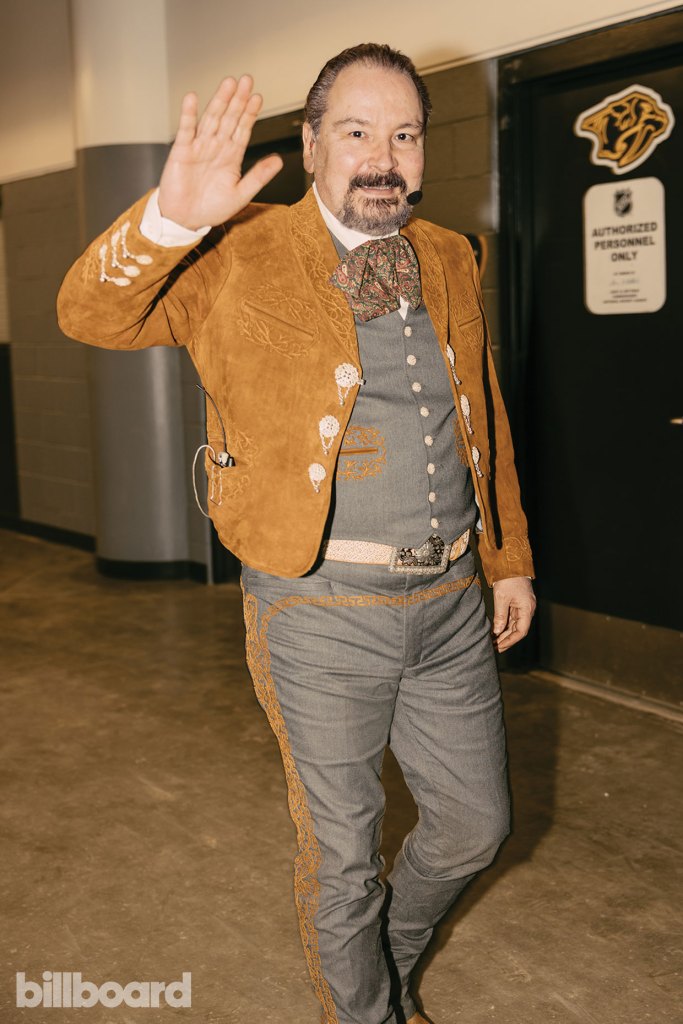

By 6:15 p.m., soundcheck has ended. In the backstage hallway, a mariachi walks by while warming up on his trumpet. A man in clown costume and face paint waves hello and passes a group of charros dressed in traditional cropped embellished jackets, embroidered tight pants and wide-brimmed sombreros. In a makeshift barn area, eight horses with meticulously groomed manes, ranging from radiant white to shiny brown and gold-coated Palomino, wait for their turn in the spotlight. Meanwhile, Pepe remains in his dressing room, where he will monitor every second of the show — when he’s not onstage, that is — to ensure it runs smoothly.

Not since Pepe’s father has anyone produced an event of this magnitude and extravagance. Legacy acts such as Joan Sebastian and Vicente Fernández were also known for singing on horses, but today such artists are anomalies. Few people can sing on top of a dancing horse whose gait is perfectly in sync with the band’s music; the discipline requires years of training for both horse and artist and a deep bond between the two. (I know that well: My uncle, Arturo “Toro” Reyes, has been working with the Aguilar family for many years. He’s the one, Pepe explained, who rides all the horses first to make sure they’re ready to go and fully trained for the jaripeos.)

Before this tour, Pepe hadn’t ridden onstage for 20 years and had been “totally disconnected” from the cowboy world — but he still makes horseback singing look effortless. He has years of experience riding horses for fun and professionally as a charro (he has won many championships at the national and state level in Mexico), and after all, he adds, he had the best teacher: His father, whose family hacienda in Tayahua — a small, humble central Mexican town of about 2,000 people — housed countless horses that were trained to perform in jaripeos.

“My father, without a doubt, was a horse whisperer. It’s a connection that only a few people have with horses. Don’t ask me. I have no clue because I don’t have it. But my father did,” says Pepe. “It consisted of being the alpha male when he needed to without use of force or violence but instead energy and grace. He was the one who taught my brother and I how to ride horses, and thank God because he was amazing. I owe everything I know to him.”

Now, Pepe has passed on that knowledge to his own children, Ángela and Leonardo, who are carving their own lane in mariachi and ranchera. Leonardo is the first of four family members to take the stage during the shows. “It has been a long journey to get comfortable,” the 23-year-old singer-songwriter says, recalling the tour’s sold-out 2018 debut at Los Angeles’ Staples Center (now Crypto.com Arena). “I lost my voice because I was so nervous. I come out with my horse — but keep in mind, I had four years less of experience — and he’s galloping at full speed. Then he sees these tiny confetti on the floor, and he stops [suddenly]. I hit myself on the saddle, but thankfully no one noticed, I don’t think.”

Leonardo has been riding since he was 13. After years of rigorous practice — involving singing songs on foot, then riding horses without singing, then dismounting, and then starting to sing and ride simultaneously — he’s at a point where he can enjoy the experience. “I’ve been working with a life coach for the last two-and-a-half years as well. He has been instrumental in helping me change my mindset and enjoy the process and my career, writing songs and enjoying the ride,” Leonardo says.

Then there’s his relationship with Caporal: “He’s my friend, my compa.” Leonardo is referring to his beloved 14-year-old horse with whom he opens the show. He has had him for nine years. “I’ve been seeing him all my life and every time we go out onstage, I give him a kiss. I seriously enjoy spending time with him. He’s a blessing.”

Eighteen-year-old Ángela, on the other hand, didn’t start singing on horses until last year, when her father finally felt she was ready. “I knew how to ride perfectly and sing perfectly,” the Latin Grammy-nominated artist says. “I was a bit frustrated because I thought I was ready a long time ago, but I’m thankful [Pepe] stopped me and made me practice more, because now I feel super comfortable.”

“Ángela was a natural. Leonardo was too but also way more atravancado [hasty], like me,” Pepe says of his kids. “Ángela from the beginning understood that your knees were key so that your voice wouldn’t shake while you’re riding and singing. If you don’t use your knees as shock absorbers, you’re going to be all over the place. The process eventually becomes automatic, like driving a car. At some point you’re able to drive the horse, position your knees and legs correctly, have and transmit confidence and sing very well.”

When Leonardo and Ángela learned about their father’s vision in 2017, it seemed unimaginable. “At this point, not even the sky is the limit for my dad,” says Ángela. Four years in, they now understand not only Pepe’s vision, but his intentions.

“We literally won the genetic lottery,” says Ángela. “I think that to be where we are and to sing what we sing is an immense responsibility, and I hope one day we make it to be as big as my grandparents and as big as my dad. It’s very humbling to be part of this.”

For Pepe, expanding on his parents’ legacy is humbling, too — and validation.

“I’ve been an indie artist for 22 years and this was the last thing that I needed to really be completely independent,” he says. “This tour is something that will never get old because it’s far bigger than me, my daughter and my son. We’re talking about culture here. We’re just passing through, and culture stays for generations to come. Banda, rancheras, horses — that was here before my father and that’ll be here long after we’re gone.”

This story originally appeared in the Aug. 27, 2022, issue of Billboard.