Kane Brown’s modest suite here at the downtown Los Angeles Westin is quiet but for the buzz of clippers currently freshening up the country sensation’s fade. It’s the night of the American Music Awards (AMAs), and Brown, nominated in three categories, sits nervously at a desk while CT, his barber, scuffs around on the beige carpet in a pair of Gucci slides.

Brown’s manager Martha Earls swipes glasses from the bathroom for a champagne toast while his stylist smooths out a purple tie-dye jacket. There’s some debate over whether Brown should wear a hat on the red carpet. The man himself is in favor — “I just want to feel like me,” he says — but Earls carries the day when she suggests it’s better to “show off the fade.”

Tonight is the latest Big Deal in a short career full of them. It’s Brown’s first awards show outside of country ceremonies, and fans of all genres vote to determine the winners, which is good news for an artist who made his name through a series of viral YouTube country covers. (Billboard’s part company, Valence Media, also owns dick clark productions, which produces the AMAs.) “I just think it’s going to happen,” says Nikki, a member of Brown’s management team. She’s wearing Kane Brown merchandise head to toe, including her slippers. “I wonder who you’re going to be standing next to on the carpet. Cardi? Migos?”

Trending on Billboard

Brown shrugs. “I can’t really talk right now,” he says, pointing to the whitening strips on his teeth, though he is able to comment on some mozzarella sticks he had last night at The Nice Guy, a hot spot in West Hollywood. “They’re the best I’ve ever had.”

He hasn’t been eating haute bar food for long. Three years ago, Brown was working at FedEx and trying to join the Army, which didn’t approve of his neck tattoos. In that short time, he has gone from viral sensation to one of the biggest country artists in America, skipping over the usual Nashville road map of radio tours and dive bars.

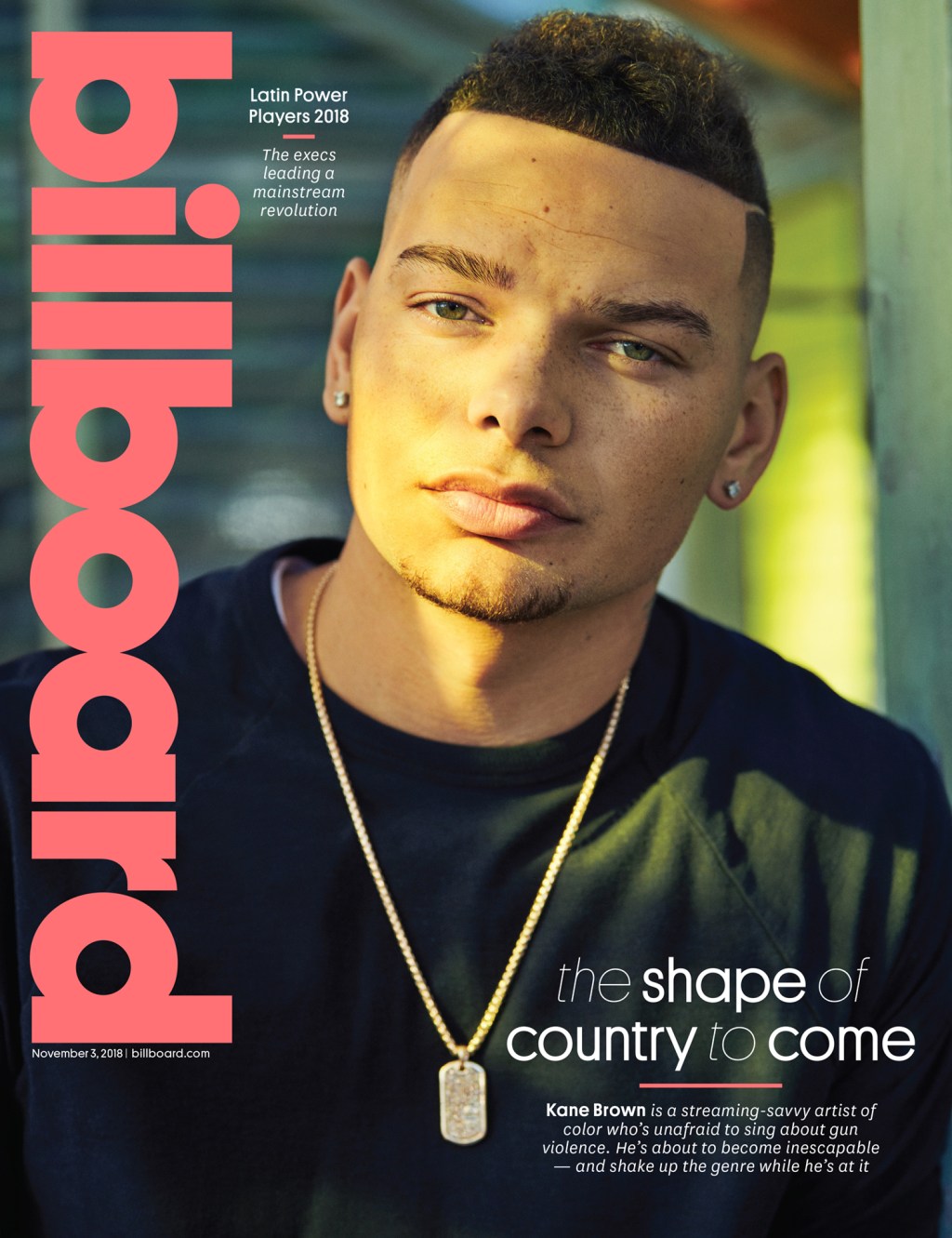

With songs that are meant to slide into a playlist between Khalid and Carrie Underwood, Brown’s closer to what the average American actually looks like, in a generation where identity is more fluid — and crucial, and debated — than ever. Brown is biracial, and while he hates to be taken as a token, he understands his significance as a rare nonwhite face on Music Row. Nor is he trying to blend in. He doesn’t, for example, have a deal for a line of cowboy boots. Instead, he’s a New Era brand ambassador for the 2018-19 football season. In Brown, fans see themselves — and it’s resonating far beyond Nashville.

Brown is selling out arenas on his Live Forever Tour, his self-titled LP went platinum, and in 2017 he became the first-ever artist to top all five Billboard country charts at once: Top Country Albums; Country Digital Song Sales, for the double-platinum single “Heaven”; and Country Airplay, Hot Country Songs and Country Streaming Songs for the triple-platinum “What Ifs,” his duet with Lauren Alaina. With each new record, he’s forcing Nashville to reconsider what it means to achieve mainstream success, and how to get there.

In a few hours, Brown will appear at the AMAs to present a prize to XXXTentacion’s mother, striding comfortably across the same stage that will have just hosted performances from Taylor Swift (with a giant snake), Imagine Dragons (with a flaming car) and Cardi B (with Dolce & Gabbana pompom hot pants). This ain’t the Country Music Association (CMA) Awards, where the night’s antics are often confined to Brad Paisley and Carrie Underwood’s family-friendly zingers. Brown, in Off-White sneakers and that purple jacket from the designer Amiri, a favorite of LeBron James, fits right in here. His music does too: He’s singing in his warm Southern baritone about partying and love but also about growing up in poverty. Many of his fans might not know about Porter Wagoner, but they sure know about Post Malone.

With his new album, Experiment, Brown is about to become inescapable, arguably changing the future of country forever. “A die-hard country fan, they’re not going to a Drake concert,” says Brown. But those Drake fans? They’re coming to him, and they’re waiting outside the AMAs red carpet, screaming his name. Freshly shorn and dressed, Brown heads down the hallway humming Zedd and Maren Morris’ “The Middle” with a quiet swagger in his step, ready to greet them.

As many fans as Brown has, there are plenty of folks who wish he would stay out of country altogether. To them, he symbolizes an almost deep-state-like assault on tradition. Experiment, however, contains one of the most “country” songs from a male artist on Music Row this year: “Short Skirt Weather,” a bit of Alan Jackson-era tongue-in-cheek pop/honky-tonk. Despite Brown’s come-up covering George Strait in those now-famous YouTube videos, people still feign surprise when he mines country history. (For the record, Experiment uses just about every instrument in the lexicon of twang: Dobro. Banjo. Mandolin. Slide and steel guitar. Fiddle. Ganjo.)

“There was a woman the other day saying that it’s awesome to see someone bringing back ’90s country, but she was not expecting me to be the guy to do it,” says Brown the day before the AMAs, sitting at a pub in an upscale strip mall in Malibu, Calif. “And my first question was, ‘Why?’ I’m doing the same thing as everyone else in country music. So why am I the one you don’t expect?”

Brown, in a plaid shirt, jeans and diamond studs, throws his hands up in the air, because he knows why. “The race card,” he whispers. He doesn’t really like talking about it because he doesn’t want to exploit it. But that doesn’t stop him, either. “Right now, [my race] does matter,” he says. “People always say, ‘There are plenty of black country artists out there! There is Charley Pride! Darius Rucker!’ That’s all they can name. They don’t understand what we go through, and a lot of people who are fans of traditional country music, as they call it, look at us and aren’t going to say, ‘Y’all like country music.’”

Those people are pretty easy to find online. They’re also nothing new. There’s always a segment of country fandom that wants things to stay the way Hank done it. But with Brown, the language is of a particular school: They’re quick to point out his “hip-hop” or “urban” influences as a reason they don’t like his fans or what he has to say. They credit his success to artifice and insist he’s a product of the industry. You might as well say “Make Country Traditional Again.”

Experiment may be as much Justin Timberlake as it is Alan Jackson, but no more so than the work of Dustin Lynch or Thomas Rhett. People who are perfectly content with white singers like Chris Stapleton digging into soul influences attack Brown for his tarnishing of tradition.

“Everyone should have equal opportunities and equal rights, but you can’t even have an opinion without somebody going off on you,” he says. “That’s what’s wrong with this world today.” That divisiveness is what inspired Brown to write “American Bad Dream” shortly after the mass shooting in Parkland, Fla. The song, about violence at schools and by police, is shockingly forward, given how Nashville barely touches the topics of gun control and racial injustice. “Now you got to take a test in a bulletproof vest,” sings Brown. “Scared to death that you might get shot.”

“It’s messed up, but so real,” he says. “And that’s what country music is: real. It’s a risk for me to write this song, but I was trying to bring up an issue that wasn’t being talked about in music other than by Childish Gambino.” Brown stirs his bowl of chili, tensing up. He’ll talk about the song, but he won’t discuss specific political viewpoints. “There’s still half of the world that doesn’t believe what you believe in, even if you say the smartest thing.”

“We’ve been systematically programmed to let stereotypes lead the way,” says Brown’s tourmate Jimmie Allen, who, as a black country artist, has encountered plenty of them himself. “Because the stereotypical country guy is supposed to be from Georgia and is supposed to be white.”

Meanwhile, Brown is finding an audience outside the United States. When the Latin American market sees him, says Goodman, “they say he looks like them.” Brown, who joined Camila Cabello on a duet version of her hit “Never Be the Same,” could be country’s ticket to global growth.

“He is expanding us and our format,” says Brad Paisley, who took Brown on tour this past summer.

Brown sounds like the world at large, too. His songs describe modern life for the Instagram generation and beyond: binge-watching Friends, falling in love, dealing with hardship and regret but looking for fun, too. And writing, of course, about his own experiences.

“What better gift for country music than a fascinating life?” says Paisley. “He’s not singing songs where he’s role-playing. He’s singing from a place of truth. And that’s so powerful for country music.”

The life Paisley refers to is fascinating indeed, but it was also hard. Growing up poor in Georgia and Tennessee, Brown shuffled between homes with a single mother who loved country music, sometimes sleeping in the car. He helped his pawpaw milk the cows and did plenty of dodging the slings and arrows of the broken American dream — the racial slurs, the overdoses that took his friends, the bipolar disorder and depression that plagued his family, the temptation that could’ve landed him in jail, like the one that houses his father (and his stepfather, who abused him).

Brown’s father has been incarcerated since 1996. “He’s a drummer, which I didn’t even know,” says Brown, who played sports until he was forced to join the choir (he and his “What Ifs” partner, Alaina, went to the same middle school and sang together there). “He brags about me and talks about how good he is on the drums. I always joke with him and say that I’m going to hire him when he gets out.”

It’s easy to see why Brown might want to stay connected to his roots, given how quickly success has come. Running away, though, would have been equally understandable. Instead, for his debut he wrote “Learning,” a brutally honest depiction of abuse and survival. He still goes home any chance he gets. A few days ago, he was back in Chattanooga, Tenn., hanging around the Walmart parking lot, shooting the shit with a couple of old buddies. “You’re so bored, you just talk about everything,” he says, sipping a Coors Light. “It’s like church. A redneck church.”

Now Brown lives outside Nashville with singer and music-management student Katelyn Jae — who, a few days after the AMAs, became his wife. The other day, he heard Sara Evans’ “Suds in the Bucket” on the radio. He loves the song, but it made him think about how country music is still clinging to images of the old days and not tackling more real-life stories with language that people actually use.

“How do you still expect us to write like that? Kids are streaming,” he says. Brown takes a sip of beer and adds, firmly, “You have to adapt. Country music? People want it [to sound like] the ’90s, maybe the ’80s, or further back.”

In many ways, Nashville is still there too. The town is too enamored with traditional radio to completely understand Brown’s rise — the viral build, the power of social media — and dismissed much of his initial groundswell as fabricated. (This predates Mason Ramsey, aka Walmart Yodeling Boy, who owes a lot to Brown.)

“That was possibly the hardest thing, being told that something is not real and people not believing you,” says Brown. “But they’re living in the past.”

It doesn’t really matter what Nashville thinks here at the AMAs. Still, Brown is focused. He rides to the ceremony in almost complete silence. Later — after he has presented an award, Tracee Ellis Ross has rallied the crowd to vote and Swift and her snake have slithered — Taran Killam and Leighton Meester appear to present favorite male artist, and Nikki was right: Brown’s a winner. He hugs fellow nominee Rhett — who shoots him a wink — and heads to the stage a little bewildered. “First off, I feel like I’m about to pass out,” he says before thanking his manager, his team and his fans. “I love everybody,” he says. Soon he’ll learn he won all three of the awards he was up for, including favorite album, country and favorite song, country. No other first-time country nominee has won as many AMAs in one shot.

Will the naysayers go silent now? Probably not. They may only get louder as Brown becomes harder and harder to ignore, shaping country music in a mold that thrills some and enrages others for the very same reason. But Brown doesn’t need approval. He knows where he’s heading now.

“I don’t think it’s about sending a specific message” to detractors, Brown says two weeks later, calling on the way home from his honeymoon in the mountains of Tennessee. “I try to focus on my fans, who I know have been there since day one. This is about us all building something together.”

Ain’t No Topping Him Now

3: Nominations and wins at the AMAs in October. Meanwhile, he was not nominated once for the 2018 CMA Awards.

1.8 billion: Total on-demand streams in the United States. He has three top 10s on the Country Streaming Songs chart.

5: Simultaneous No. 1s on all five of Billboard’s country charts in 2017. He is the first artist to top all of them at once.