When Western policymakers ask me what “gender apartheid” means, my response carries the weight of personal experience: One must be a woman like me, living under two generations of Taliban rule in Afghanistan, to truly grasp what is happening. It is not a mere theoretical notion; gender apartheid is the horrific reality that the Taliban is inflicting on millions of women and girls. It is necessary for the international community to recognize the situation for what it truly is and codify it as a crime against humanity under international law.

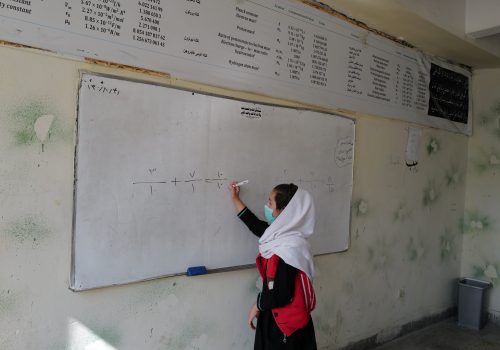

Since the Taliban seized control of Afghanistan on August 15, 2021, the landscape of rights for women and girls has deteriorated drastically. For Afghan women like me who are in their forties and fifties, this dehumanizing discrimination is not a surprise. The Taliban’s use of ideological and systematic discrimination has remained consistent over the decades. It is aimed at erasing women from public life, restricting freedom of expression, dismantling democracy, and banning cultural rights, including music, sports, and the practice of religions other than their own extremist interpretation of Islam. The Taliban’s return to power is forcing Afghan women to relive the same nightmare that they experienced in the 1990s when the group first came to power. It is devastating that our daughters are now going through the same trauma that their mothers did two decades ago, even though we fought with our flesh and blood to bring about relative change during the period of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan.

On a daily basis, I speak with women and girls from across Afghanistan who find it harder and harder to see any light at the end of the tunnel.

What is frustrating is that there are many diplomats, both regionally and globally, who are willing to give the Taliban the benefit of the doubt and are pursuing more unprincipled engagement with them. Too often, I have heard policymakers talk about a “moderate” or even “like-minded” Taliban, clinging on to the misguided idea that the Taliban have changed. This narrative emerged during the US-led peace process. However, the past two-and-a-half years of Taliban control over Afghanistan have proven it to be wrong.

In reality, the so-called “changed Taliban,” has been imposing an extreme form of gender discrimination since August 2021. Upon seizing power, the group almost completely removed women from government positions and replaced the former Ministry of Women’s Affairs (MoWA) with their feared morality police—the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice.

Subsequently, the Taliban issued around a hundred decrees against women and girls, including banning girls from schools beyond grade six and universities; and employment at nongovernment organizations (NGOs), United Nations (UN) bodies, and even humanitarian agencies. They have shuttered women’s beauty salons and forbidden women from going to parks or gyms, while imposing strict dress codes on them and severely restricting their freedom of movement and access to life-saving necessities such as health care and aid. Those who dare break these rules risk arbitrary detention, imprisonment, and torture.

There are also unwritten rules that are just as nefarious. For example, the Taliban has instituted a mass expulsion of women from government ministries and replaced them with men, mostly members of the Taliban. Meanwhile, NGOs that still operate have largely been forced to replace female directors and other senior staff with males. Consequently, many women-led NGOs are struggling, forced to choose between shutting down or replacing their female staff and board members with men. The Taliban’s Ministry of Economy also largely refuses to approve any NGO programs that are designed to benefit women and girls.

It is true that even under the previous internationally backed government, between 2001 and 2021, violence against women was endemic and widespread. The difference, however, was the existence of legal frameworks and institutions that could offer some measure of protection and accountability. The justice system, although flawed, was showing signs of progress, while instruments such as the Elimination of Violence Against Women Law, Family Response Units, the Prosecutor’s Office, and other protective mechanisms made a genuine difference. These mechanisms prosecuted perpetrators, provided safe houses, and gave other protections.

Since the Taliban took power, it has dismantled the entire legal framework, including the constitution, and institutions such as the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, the MoWA, and Gender Units from various government bodies that were mandated to monitor, document, and refer cases of violence against women. Today, women victims of violence and injustices have nowhere to go; they are now left to fend for themselves.

On February 20, UN experts and others labeled Taliban policies as tantamount to gender apartheid, which they asked to be recognized as a crime against humanity.

On a daily basis, I speak with women and girls from across Afghanistan who find it harder and harder to see any light at the end of the tunnel. A female lawyer, who was granted anonymity given the dangers facing women who speak out, recently told me: “It is a state of hopelessness. The ones who can afford, they flee, and the ones who cannot, they stay and suffer. It feels like a slow and painful death.”

In less than three years, the Taliban has reduced millions of women and girls to a subhuman status, depriving them of bodily autonomy and their most basic rights. This is what we mean when we talk about “gender apartheid.”

Despite this, women and girls in Afghanistan have refused to remain silent. Hundreds of brave women from across the country have protested against the Taliban’s policies. These peaceful protests have been met with live ammunition, water cannons, and beatings. Scores of women protesters have also been arrested, detained, tortured, and sexually abused in the custody of the Taliban.

Outside of Afghanistan, those of us in the diaspora continue to contribute to our country. Human rights defenders and activists are documenting violations and engaging with international policymakers to raise awareness about the situation inside Afghanistan and the systematic persecution of women. In Germany, human rights defender Tamana Paryani embarked on a hunger strike to demand that the international community recognize gender apartheid in Afghanistan. Other international human rights lawyers and gender experts have been making the legal case to the United Nations and its member states, either individually or through initiatives such as the End Gender Apartheid Campaign.

The push for recognition of gender apartheid in international law, which is finally gaining real momentum, represents a significant act of international solidarity with women of Afghanistan. Simultaneously, this demand sends a clear signal that the world does not accept the Taliban’s attempts to erase women from public life in the name of religion and culture. Most importantly, the recognition of gender apartheid as a crime against humanity would provide a practical tool for those of us working to ensure international accountability for the Taliban’s crimes, while also strengthening international law by making it evolve in a manner that bolsters rights for everyone.

The deepening human rights crisis in Afghanistan underscores the dire need for global attention on the plight of the country’s women. A journalist I recently spoke to, also granted anonymity because of the dangers of speaking out, captured the situation in painful detail: “In Afghanistan, there is only darkness and hopelessness now—nothing else,” she told me.

The world must wake up to these atrocities and make it clear, once and for all, that crimes committed against people because of their gender identities will never be tolerated.

Horia Mosadiq is a human rights defender and journalist from Afghanistan with over thirty years of work experience and activism. Mosadiq was a reporter when the Taliban first came to power in 1996.

Further reading

Thu, Oct 5, 2023

Gender apartheid is a horror. Now the United Nations can make it a crime against humanity.

New Atlanticist By Gissou Nia

The international community has an opportunity to codify the crime of gender apartheid in the United Nations’ crimes against humanity treaty. Learn more about gender apartheid from the Atlantic Council’s Gissou Nia.

Mon, Aug 14, 2023

Afghanistan’s next generation must rise above the Taliban’s ‘reality’

New Atlanticist By

The Taliban are not and never were an acceptable alternative to a democratic state in a pluralistic society such as Afghanistan.

Thu, Mar 16, 2023

I was once denied an education in Iraq. This is why the Taliban’s prohibition on female education matters.

MENASource By Nibras Basitkey

As an Iraqi refugee who understands the importance of education, I recognize that achieving gender parity in education is critical for Afghanistan’s long-term economic growth and prosperity.

Image: A girl sits in front of a bakery in the crowd with Afghan women waiting to receive bread in Kabul, Afghanistan, January 31, 2022. REUTERS/Ali Khara.