The Getty

Beautiful things: paintings, books, sculptures, photographs, artistic finds.

Web: getty.edu

Blog: blogs.getty.edu

Tags

-

loading tags

One painting, front, back, and in different light.

Notice the glossy parts? This was painted with two types of house paint that have different levels of gloss. Artists in Brazil in the 1950’s took advantage of fast-drying industrial paints new on the market.

Concrete artists in Buenos Aires like Hermelindo Fiaminghi (work above) were interested in experimenting with paint types and application techniques. The combination of these factors made some works look more like industrially produced objects, however, paint was applied and manipulated by the artist’s hand.

Hermelindo Fiaminghi is one of the Concrete artists on view currently in Making Art Concrete, on view until February 11. A show that asks, “What is the role of art in society?” Artists after WW2 in Argentina and Brazil were grappling with this question and rejected traditional painting to create artwork so precise in conception and execution that it formed its own material, or “concrete,” reality.

These “Concrete artists” were interested in experimenting with format, shape, construction, paint and material—art was to be a part of everyday life.

Making Art Concrete is one of four #PSTLALA exhibitions currently on view at the Getty Center that spotlight Latin American art and Latino/a artists in relationship to Los Angeles.

Seccionado no. 1/ Sectioned No.1, 1958, Hermelindo Fiaminghi, alkyd on hardboard. Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. © Estate of Hermelindo Fiaminghi

Morocco in the 1960s

A photographer and practicing architect, Wim Swaan illustrated eighteen books on the art and architecture of cultures around the world. About 860 digitized images from the Wim Swaan photograph collection were added to the Open Content Program, available to download and use for any purpose.

By Kristen and Bryan from our manuscripts department

“December 1 has come to be known among art and AIDS organizations as Day With(out) Art (or World Aids Day).

Now in its 28th year, Day With(out) Art is a call to action against the AIDS pandemic and its devastating effect on art and culture.

This year, we focus on #MyRightToHealth and are motivated as well by current efforts to pass a bill that would eliminate the tax deduction on medical expenses—a deduction that helps almost 9 million Americans a year offset the financially devastating cost of medical crises, chronic illnesses, and disabilities.

As curators of manuscripts, this day prompts us to reflect on the enduring relevance of centuries-old images in our collection, specifically, one that reveals the vulnerability of the human condition and celebrates compassion, not only with thoughts and prayers but with actions.

“Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.”

Taken from the Gospel of Matthew, Christ’s words about charity are written in Latin above this scene of a nun feeding a leper in a hospital. Even in the Middle Ages, medical care was available to those with pre-existing conditions and terminal illnesses, though treatment was rarely provided by physicians.

It was clerics who were tasked with ministering to the physical and spiritual needs of the sick. Meals and medicine were communally provided after admission to a hospital, but some of the poorest members of society were compelled to raise funds for their care. The stigma attached to diseases such as leprosy, the plague, or later syphilis, however, cut across all social classes.”

Image: Initial D: A Woman Feeding a Leper in Bed, 1275-1300, Unknown. J. Paul Getty Museum

The Italian countryside as painted in the 1780s by Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld.

Two shepherds discover a tomb. See the full 1655 painting by Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione.

Been waiting for scarf weather.

Etruscan disc earrings, a detail.

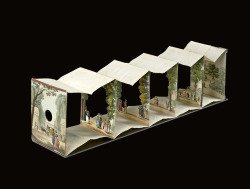

An optical device made between 1825 and 1870 with a miniature garden scene.

How do you wear Pre-Columbian nose, ear, and lip ornaments?

What are the artistic connections between the cultures of the ancient Americas?

What material did the Incas consider to be more precious than gold?

Kim Richter from the Getty Research Institute and Joanne Pillsbury from the Met Museum, the curators of Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas, and Emma Turner-Trujillo, the project’s research assistant, are going to answer questions on The Getty’s Instagram.

Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas explores the development of luxury arts from 1200 BC to the beginnings of European colonization in the sixteenth century. Made of precious metals and other substances esteemed for their color and luminescence, these works were imbued with sacred power by the people who created and used them.

In the ancient Americas, metals were employed primarily to create objects for ritual and regalia rather than for tools, weapons, or currency. The use of gold, transformed into objects for gods and rulers, provides the central narrative and trajectory of the exhibition, from Peru in the south to Mexico in the north.

However, other materials were often deemed far more valuable. Jade, rather than gold, was the most precious substance to the Olmecs and the Maya; and the Incas and their predecessors prized feathers and textiles above all.

These works were often transported across great distances and handed down over generations, making them a primary means by which ideas were exchanged between regions and across time. Crucial bearers of meaning, luxury arts were especially susceptible to destruction and transformation; thus the works in the exhibition are rare testaments to the brilliance of ancient American artists.

Leave your questions in the comments on this Instagram post, and we’re looking forward to getting them answered!

Over 70 exhibitions across Southern California explore Latin American and Latino/a art in dialogue with Los Angeles.

Four on view at the Getty Center:

Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas:

This major international loan exhibition featuring more than 300 masterpieces, traces the development of luxury arts in the Americas from about 1000 BC to the arrival of Europeans in the early sixteenth century. Recent investigation into the historical, cultural, social, and political conditions under which such works were produced and circulated has led to new ways of thinking about materials, luxury, and the visual arts from a global perspective.

Making Art Concrete:

Combining art historical and scientific analysis, experts from the Getty Conservation Institute and Getty Research Institute have collaborated with the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros to examine the formal strategies and material choices of avant-garde painters and sculptors associated with the Concrete art movement in Argentina and Brazil. These works of geometric abstraction, created between 1946 and 1962, are presented alongside information on the way artists pioneered new techniques and materials.

The Metropolis in Latin America:

Focusing on six capitals—Buenos Aires, Havana, Lima, Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, and Santiago de Chile—this show presents the colonial city as a terrain shaped by Iberian urban regulations, and the republican city as an arena of negotiation of previously imposed and newly imported models, which were later challenged by waves of indigenous revivals.

Photography in Argentina: Contradiction and Continuity

Comprising three hundred works by sixty artists, this exhibition examines crucial periods and aesthetic movements in which photography had a critical role, producing—and, at times, dismantling—national constructions, utopian visions, and avant-garde artistic trends in Argentina.