Games not only have the potential to change the world for the better, but already do so. Across the world, game developers are leaning into their expertise to make complex topics—like climate change—approachable and even engaging.

Evidence suggests players are eager for more great climate games. We’re here to help you make those games.

This report is a critical resource for the game industry, bringing new qualitative research to bear with a robust examination of current game development practices and approaches.

In this report, you’ll learn how games can be made to drive real-world change, and explore the four main challenges teams have faced when creating their climate games.

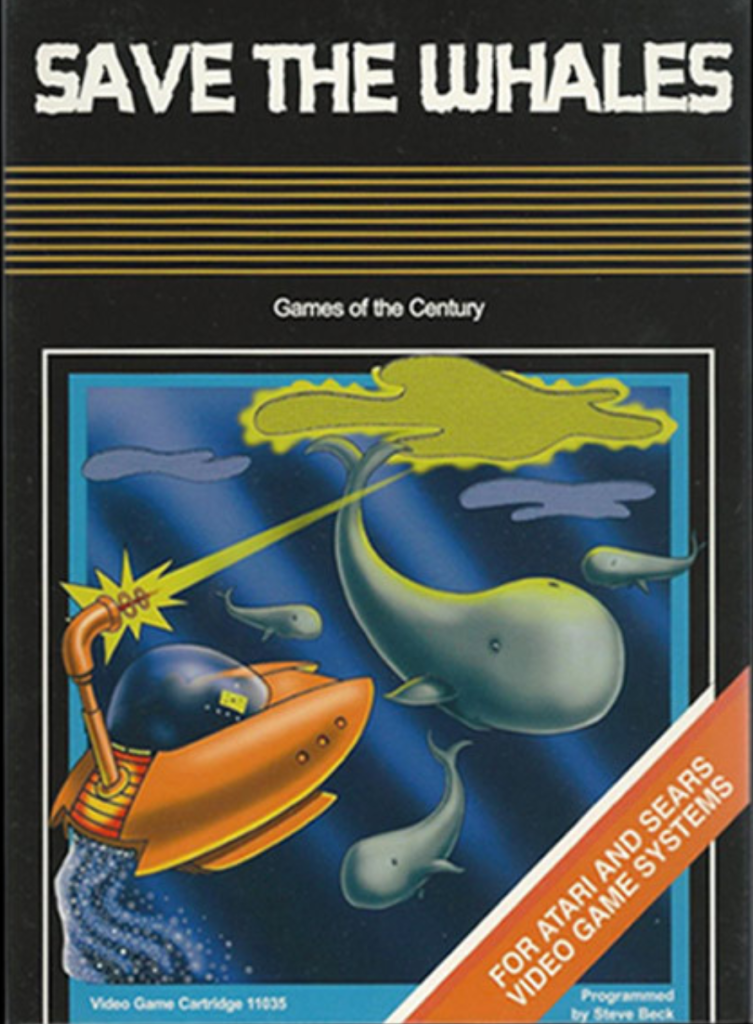

We’ll start with how a 1982 game designed to save whales underscored the the power of play—both as a force for change and as a method of learning.

What’s in the report?

Main analysis: Gaming for climate action

Challenge 1: Determining why you want to make a climate game

Challenge 2: Know your practical plan for impact

Challenge 3: Making reality fantastical

Challenge 4: Making your game fun

We saved the whales

Ned Wickham looked out toward the sea and spotted something terrifying—a giant mass struggling in the water. It took him a day to build up the courage to approach. Local newspapers described what he found as a “strange visitant from strange seas.” It was a blue whale, lost and stuck in the Irish harbor of Wexford.

Today, this same whale’s skeleton fills Hintze Hall in London’s Natural History Museum. It serves as a monument to a majestic species which was very nearly hunted into extinction as recently as 40 years ago. It’s also a celebration of the fact that whales were saved. The story of the international effort to prevent the end of whalekind is an inspiring one, representing a massive environmental success story. Disaster is not inevitable. Society can adapt and change at scale to collectively build a better world. This story is also educational. Saving the whales required the combination of public imagination, high levels of organization, and capital incentives, all which ultimately led to global regulation.

This success story is exciting not only because of its outcomes but also because of the way whaling had been interwoven into the fabric of international society. Whaling powered the very aspects of life many of us now take for granted, and so changing public perceptions and behaviors connected to whaling would be no small task. From oil-powered lanterns to industrial lubrication, whale oil powered lighting and drove machinery for centuries.

Then, the inevitable happened: whalers started having trouble finding new whales to hunt. Whales were being killed faster than they were being born. They were rapidly approaching extinction. While electricity and petroleum refining provided alternatives, whale oil was still more reliable and familiar.

People paid a premium for it.

Technological progress and the development of alternatives alone would not save the whales; the applications for lubrication only continued to expand. The beginnings of the rise of digital computers certainly didn’t help. To this day, computers, game consoles, game controllers, even the Internet all require lubrication to function.

Either society would be forced to develop quality alternatives when all whales had been hunted to extinction, or society could be convinced to move through the uncomfortable process of transformation sooner, in time to save the whales.

Environmental activists around the world rallied to facilitate the latter scenario. In 1975, Greenpeace led the charge with their Save the Whales campaign. Greenpeace’s multifaceted efforts shifted the public imagination of whales from a harvestable resource to intelligent beings. Their campaign became one of the organization’s “first major victories” as the International Whaling Commission was influenced by public pressure to ban commercial whaling from 1986. The ban has (mostly) held to this day, and has played a huge role in slowing global warming—it turns out that whales fertilize phytoplankton, the tiny sea creatures which produce half of the world’s oxygen from vast amounts of CO2. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that when it comes to climate impacts, one whale is worth a forest of a thousand trees.

Saving the whales through gameplay

The campaign also inspired one of the first digital climate games. An electrical engineer and computer scientist by training, Stephen Beck ran a small company in the early days of Silicon Valley where he designed systems with microprocessors. His projects were varied, ranging from toys to multimedia art to bespoke systems for businesses to games.

Beck was intrigued by the emerging possibility for interactive media to combine social concerns with entertainment. When he saw footage of Greenpeace’s efforts, he thought, “Well, wait a minute. This is an important concept. I want to make a video game about it.”

The game was built in 6502 assembly language for the Atari 2600 around 1982—meaning the game was built in a low-level programming language designed for the Atari’s specific microprocessor, without any support from the development tools we enjoy today. It tasked players with protecting whales from whaling ships as they migrated south and north. Beck wanted to include real whale songs in the game, echoing Greenpeace’s effective empathy-building campaign, but they didn’t fit; the entire game ultimately used just 2 kilobytes of memory. (For context, 2 kilobytes can fit roughly 0.125 seconds of a song streamed from Spotify; modern games don’t face these memory limitations.)

While he reached out to Greenpeace to explore possible collaborations, he never heard back. “If I could go back, the one thing I would try [to change] would be to really make that connection with Greenpeace,” he reflects. Without Greenpeace’s support, however, the economic realities for manufacturing and distributing the game did not line up and the game did not reach a wide audience. In fact, its largest release would actually come in 2002, with CGE Services printing a limited run to be featured at that year’s Classic Gaming Expo.

But Beck remained a big believer in the power of play, both as a force for change, and also a method of learning how to effectively solve problems. He even included games and puzzles in his recruiting practices to ensure that his team would have the right mindset to work in the rapidly changing world of early computing.

This creative problem-solving mindset paid off when Beck and his team were asked by supermarket chain Safeway to invent and build an Energy Management System—a microprocessor-powered network able to monitor and control lights and refrigeration intelligently and efficiently. Beck constantly considered the impacts that technology could drive. Unlike the Save the Whales game, this project did align finances with environmental impact, reducing Safeway’s electrical usage over the years by thousands of gigawatts of power, and dramatically reducing food waste. Beck estimates that this system has ultimately saved enough energy to power a city of 50,000 for 10 years—and it paid well enough to fund more game development.

Greenpeace’s work to save the whales, Beck’s own pro-environmental work, and the story of how they did not align highlight some critical lessons for anyone interested in pro-environment projects today.

Four steps to effective climate games

We spoke with the heads of fifteen modern climate game projects from nine countries and five continents. It turns out that there are four big challenges that sit between a climate game project and its success.

If a team doesn’t see these challenges coming or if a team tries to avoid facing one of these challenges, the project never quite recovers. If many of these challenges are fumbled, the project will probably fail. (You can read more about our methodology here.)

When teams face these challenges head on and carefully think about what path forward works best for them, great things happen. It is by thinking carefully about these challenges that projects have uncovered uniquely engaging moments, innovative gameplay, world-class environmental messaging techniques, and a wider audience reach. By considering how others have successfully navigated the challenges in the past, we aim to showcase effective processes for how others can find their own way in the future.

In these linked sections, we will guide you through the four key challenges:

- Challenge 1: Determining why you want to make a climate game. The more specific your climate theme and the earlier in the project you choose it, the better. There’s no one right way to settle on a theme, but there are some common paths.

- Challenge 2: Designing for real-world change. You must understand how you want a player to change after playing your game. You must figure out who your players will be, how you mean to impact them, and how to tell if you are achieving your intent. The teams that have specific answers to these questions reach further than teams that do not.

- Challenge 3: Blending factual and fantastical representations of the world. Nearly every choice made during game development impacts how the digital world connects to players’ lives. By being intentional, you can connect with players more deeply and avoid unintended messaging. You also may have the chance to drive widespread change through your crafted imaginaries. This is our biggest section and contains perhaps our most important findings.

- Challenge 4: Making a climate game fun. There’s an inherent challenge in presenting serious contexts in an entertainment medium. The climate crisis is a recognized threat in the gaming community, and it is one of the most serious and urgent challenges of our time. You must consider how to integrate grounded climate content in a way that makes players want to continue the game.

The way ahead

The support gap

Some challenges are harder to tackle solely from within a game team. Nearly every climate game developer we spoke with brought this up: funding is hard to access. This is not shocking in an era where even the mainstream game industry is contracting, but the climate games sector is experiencing specific nuances here.

First, it is important to understand that even game developers committed to impactful projects recognize how important it is to function as a business. “It’s better to make a fun game that is commercially successful rather than just an impactful game,” one interviewed game lead told us. “We’ve worked on a few impactful projects that didn’t reach an audience. They [maybe] didn’t have the marketing budget, or didn’t have the appeal or stickiness to actually get traction. And that feels like a bit of a waste.”

Still, one of the largest challenges when it comes to bringing a climate game to market is the lack of funding support that’s existed in the past. Speaking about a past project, one lead told us: “Government bodies didn’t want to fund it because it was too much of a game. [Game] publishers didn’t want to fund it because it had too much environmental messaging.” One-third of the teams we examined told stories of getting caught in this funding limbo, even as the project’s very strength was the intersection of a game’s potential for both impact and market success.

Support has grown within the game industry in the form of cross-studio community connections. As one lead told us, “[Learning] that there are many climate game studios and games, and that there are many groups trying to help us, and that there are many people trying to deliver messaging to players—that really gave us the courage to get started with [our] project.” Teams we spoke with were eager to better connect with each other and other climate projects around the world to continue to close knowledge gaps and support each other’s efforts.

The publishing gap

We’ve found, predictably, that well-connected teams had an easier time attracting both monetary and expertise resources, and experienced teams were able to navigate development challenges more quickly than inexperienced ones. We also saw the positive impact when publishers were able to champion the values of the climate game project. Game publishers can help teams identify ways to reduce the project’s carbon impact (e.g., modifying materials and distribution plans) to better adapt gameplay to fit the game’s intended impact, and to fine-tune audience identification and engagement.

But there was a large gap here, as many climate game teams were frustrated by an inability to find a publisher willing to support them. Still, whether or not a publisher is involved, climate game teams and climate-related NGOs alike can benefit from third-party support to meaningfully connect and work together. Many game teams see clear benefits to partnering with NGOs, and NGOs see clear benefits to partnering with game teams. However, there are shockingly few examples of such partnerships in practice. The game industry and nonprofit impact organizations operate at very different speeds with different organizational and funding structures. These operational differences can create barriers to partnerships, but they are worth addressing. Organizations like Arsht-Rock have already begun working on ways to bridge these gaps to create meaningful impact and success.

The challenge of creating a successful, impactful climate game is never going to disappear. With the right support, though, we hope that the scarier or more overwhelming aspects of this work can be smoothed away so that teams can focus on the exciting challenges of crafting innovative, engaging games in these crucial contexts.

In the forty years since Save the Whales was created, evidence is building that climate games can pull this intersection off. “We’re benefiting from the fact that environmental games have proven to be successful,” one game lead said. Every award won, every demonstration of player impact, and every example of financial success builds lasting support for future projects and creates an enabling environment for future climate games.

The power of play

There will never be a simple answer to climate mitigation or resilience. There are no silver bullets for this monstrous, entangled global challenge. We will never build climate resilience or transition toward sustainability if we ignore the multitude of ways of living, thinking, believing, and dreaming that exist across the world.

Instead, effective climate response will always involve an assemblage of efforts—processes toward a better world from across the world, a series of steps along a journey toward the futures we dare to hope for. As we cover with our story on Puerto Rico’s solar transformation later in this report, enduring change can occur when a persuasive vision leaves room for people to respond in their own ways, situated in their own contexts. And games, with their reach, their impact, their resonance, their interactivity, and their playfulness, not only have the potential to be one of the best avenues for this work, but also already are a part of this work.

Usoni by Jiwe Studios critically reclaims and reframes climate migration narratives at a time when public imaginations of migration directly impact policy and lives. Out and About by Yaldi Games connects the dots between digital and local communities and sustainable access to food in an era of rising food prices and soil erosion. Terra Nil by Free Lives introduces players to the concept of ecosystem restoration, which is a process the United Nations has recognized requires broad community engagement in order to succeed. Koral by Coronado reveals the state of ocean ecosystems and highlights often hidden aspects of climate change, building connection with the beautiful, alien-like animals that are corals—a connection that may pay off as publicly driven underwater preserves are one of the most effective ways to protect these creatures while global warming continues. Daybreak by CMYK asks players to cooperatively confront the notion that reaching a better future will be both challenging and possible, and worth fighting for together.

These are very different games about very different things. But they’re all forms of climate crisis response. They engage players playfully around serious themes, and create new imaginaries together with their players.

“Playfulness can loosen us from the constraints of society and its norms and values, and help us to re-perceive what is simply considered to be accepted reality,” writes Joost Vervoort, an associate professor of transformative imagination at Utrecht University, whose Anticiplay project explores how games help realize better futures. “It can subvert and invert the ‘normal’, it can challenge existing power structures and ideologies and spark the imagination needed for new societal alternatives. With playfulness, after all, comes humor, the breaking and hacking of rules, and imaginative pretending.”

And these games we’ve featured aren’t alone. We interviewed a number of other game teams and developers who will remain anonymous in exchange for their candid thoughts. Their projects, along with many others, can be found in the Climate Game Database.

The future of climate games

A climate game team that deeply understands its goals and can weave different experts together toward those goals is more likely to succeed. In this way, a climate game project is like any game project—there are simply more disciplines to weave together and more goals to balance.

Alongside intent, resourcing continues to be a determining factor for the success of climate game projects. There is room to better understand how different teams and organizations can work together more effectively—large and small, nonprofit and for-profit, academic and professional, top-down and bottom-up. The initial cross-sector relationships are already benefiting projects, but closer relationships would pay off, helping projects connect the dots between imaginaries and action.

When teams are resourced and supported enough to think long term and build institutional knowledge, better work gets done. The next frontier of climate game research and development will require teams equipped to do both simultaneously, closing the gap between theory and practice. The more teams like these get supported, the faster this movement can grow, and the more inclusionary the worldwide climate game development space might become.

This project hopes to be a useful next step for existing and aspiring teams, a beacon among the chaos of climate response complexities. This project is also a call to dream bigger and bolder; we have not yet come close to reaching the potential of how effective, engaging, and successful a climate game can be.

Momentum is only building. Each new wave of green games is inspiring the next. NGOs like Arsht-Rock are, in parallel, rapidly learning how to develop processes, training, and support structures for ever more successful and impactful projects. As teams start with imagination, they can create real-world action. The world couldn’t imagine itself without the whaling industry. Thanks to Greenpeace, people across the world imagined a new way forward. Top-down policy change was made possible by bottom-up imagination, as it ever must be if change is going to last.

And now whales still roam our seas.

Hope engenders action which engenders hope. Pass it on.

Explore the chapters

Determining why you want to make a climate game

This chapter covers the ways climate themes emerge in the game development process.

Know your practical plan for social impact in the game

This chapter covers the ways climate games are currently designing for impact both within and around their core play experiences.

Making reality fantastical in climate change games

This chapter delves into how fantasy representations of the world can convey real-world messages or interventions.

Making your game fun with climate game design

This chapter addresses the challenge of making a game with climate or environmental themes enjoyable for players.

About the authors

Trevin York is the founder and director of Dire Lark, a game design for change studio in Edinburgh, Scotland. With fourteen years of experience leading game projects, York organizes Game Developers Conference’s Climate Workshop, is a co-author of the International Game Developers Association’s Environmental Game Design Playbook, and is a senior fellow at Arsht-Rock.

Catherine-Ann McNamara-Peach is an anthropologist and PhD candidate at the London School of Economics. Her research studies theories of change in UK climate activism and the existential and relational challenges of life in the Anthropocene. She is interested in the potential of the cultural sector to shape social imaginaries around multi-scalar climate responses.

Ariadne Myrivili is a game designer with a focus on team management, how leadership impacts design, the intentions of design, and how design effects players. She is currently working on projects centered around games’ ability to turn global events into digestible narratives to improve public response and engagement.

Seb Chaloner designed the visual assets for the report. He is a graphic designer, visual artist, and design researcher. His current work explores how diffuse design, ArtScience, and cultural probing techniques can facilitate communities to become active in mitigating the biodiversity crisis. Seb is also a lecturer at the School of Arts & Creative Industries, Edinburgh Napier University, with a focus on active learning rather than preaching from a podium.

Special thanks to: Sam Alfred, Carlos Coronado, Paula Escuadra, Elena Höge, Max Musau, Grant Shonkwiler, and Clayton Whittle as well as the Arsht-Rock team, especially Jessica Dabrowski, Kathleen Euler, and Kashvi Ajitsaria.

Our methodology

This report is a critical resource for the game industry, bringing qualitative research to bear with a robust examination of actual development practices. The research was conducted by a multidisciplinary team that deeply understood both game development and research. To learn more about their methodology, click here.